The composer Tommaso Antonio Vitali is well known for the poignant Chaconne attributed to him. However, he also pursued a successful career as virtuoso violinist in Modena from around 1675. Vitali interests us because in 1685 he petitioned the Duke of Modena to request compensation for a fraud which had occurred: he had paid the considerable sum of 12 doppie for a violin labeled Nicolò Amati, only to discover that the instrument was in fact by Francesco Rugeri ‘detto il Per’ and was worth less than a quarter of what he had paid.

This is probably the earliest available document in which Francesco Rugeri is mentioned as a violin maker – and it shows he was already a first-class one, considering that one of his instruments had been passed off as an Amati to an experienced and talented musician such as Vitali.

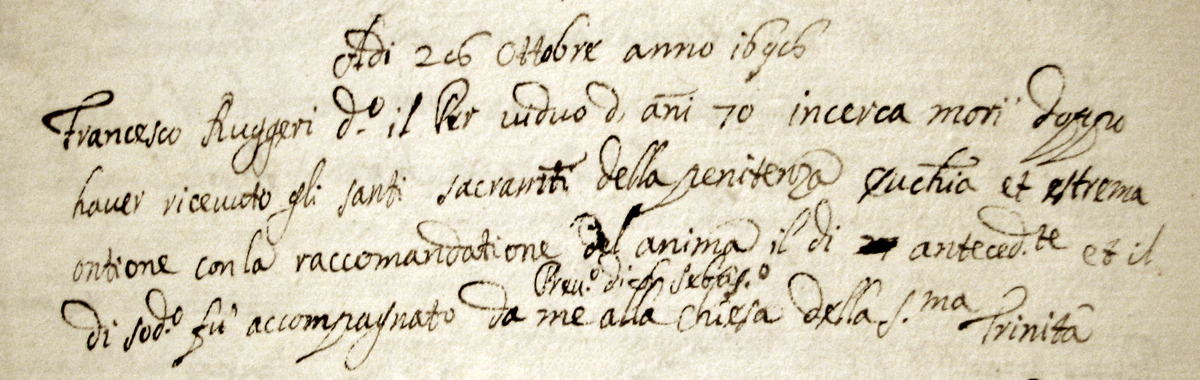

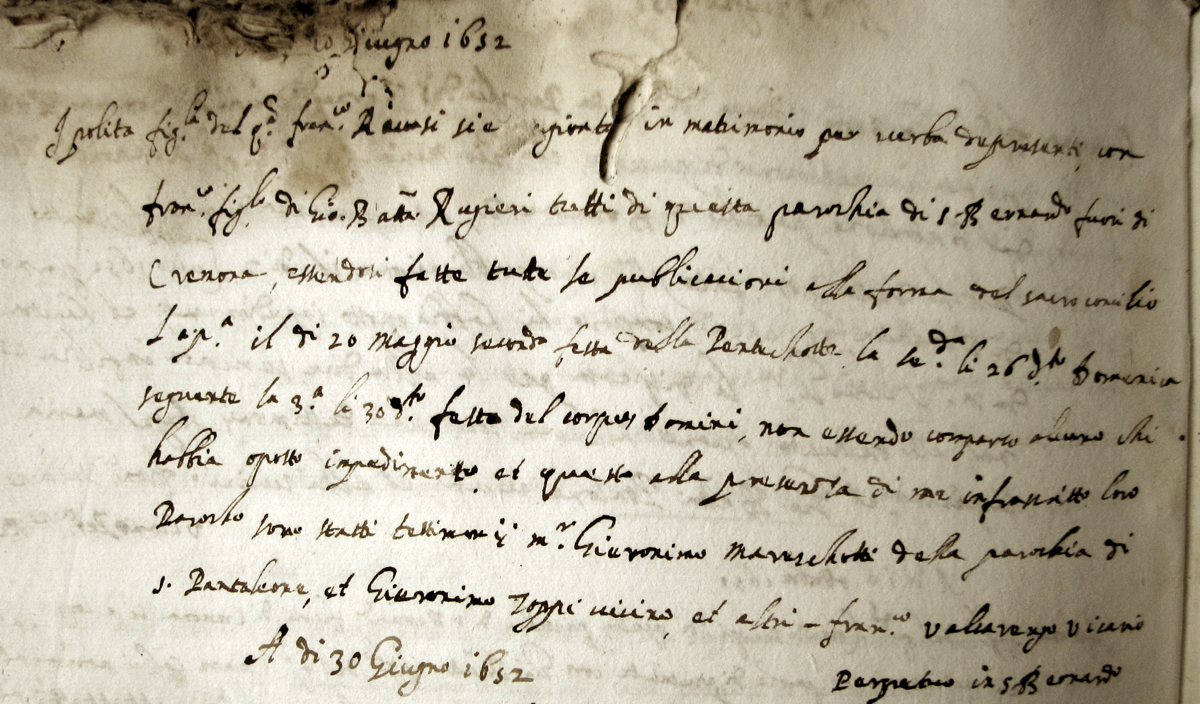

We do not know exactly when Rugeri was born. The earliest-known document that mentions him dates from 1652, when he married Ippolita Ravasi in the parish of San Bernardo. Assuming he was of normal marrying age (around 20–25), we can surmise that he was born in or around the years of the plague that ravaged Europe from around 1630. This would also indicate that he was only a few years younger than Andrea Guarneri, who was born in 1623.

Francesco Rugeri’s wedding is recorded in the marriage book of the parish church of San Bernardo, 1652. Photo: courtesy Carlo Chiesa

The Rugeri family did not live in the city of Cremona, but in the immediate outskirts, right outside the walls that fortified the town. This suggests that they were farmers, since there was not much else that would occupy a family in that area. At the very least it seems safe to say that it was unlikely that Francesco was born into a family of artisans. At present we have no documentary evidence of his training, although there is little doubt that the Amati workshop would have been the best – perhaps even the only – workshop in Cremona at that time in which a young man could have learned the craft of violin making.

As is well known, no documents exist that list the workers employed in the Amati shop. However, parish census records do report the names of the people living in the Amati household, at least from 1640. It is through these that we know of the connection between Andrea Guarneri and Nicolò Amati. The name of Francesco Rugeri is never listed in the Amati census records, but it is possible that he was working with Amati without residing in his master’s house, given that his home was within reasonable walking distance of the Amati workshop. Interpreting census documents sometimes requires reading them for what they omit, as well as what they state plainly.

There is little doubt that the Amati workshop would have been the best – perhaps even the only – workshop in Cremona at that time in which a young man could have learned the craft of violin making

For example, in the years 1657, 1658 and 1659 there are no apprentices recorded as living in the Amati household. But looking at the quantity of existing instruments from these years, it does not appear that the Amati workshop was slowing down its production; on the contrary, it seems to have been operating at full capacity. Nicolò’s son Girolamo II, who was born in 1649, was still a child and unlikely to have been of significant assistance in the workshop. Of course the main assistant to Nicolò could still have been his former pupil Andrea Guarneri, who lived next door, but it is a plausible assumption that a younger assistant could have entered into the workshop. And it cannot be by chance that in 1658 Nicolò served as a godfather at the baptism of Francesco’s son Giacinto; clearly the old master was well acquainted with the young Francesco.

The Giacinto who was Amati’s godson died in infancy, but Francesco had four more sons, all of whom were involved in violin making to some extent: Giovanni Battista was born in 1653, Giacinto in 1661, Vincenzo in 1663 and Carlo in 1666.

Given the family connection between Francesco and Nicolò Amati, it seems to be a reasonable conclusion that from at least 1658 Francesco was involved in making violins. Yet to my knowledge there are no instruments bearing a label of Francesco from this early period. Perhaps for a few more years he continued working for Amati. However, soon enough he set up his own workshop and began his own production.

Surviving church and notary records suggest that Francesco never resided in town, but always in the outskirts. It is possible that he had a workshop in town, but there is no proof of this. Given Francesco’s predilection for living in the country, it seems most likely that his workshop remained in the immediate proximity of Cremona but outside the city walls, in all probability at his own home.

One of the most intriguing unanswered questions in Cremonese violin making is the training of Antonio Stradivari. From a simple biographical point of view, Stradivari was of the right age to apprentice to Rugeri in the 1660s. At this point, Francesco’s sons were still too young to help their father and yet Rugeri’s output from this period suggests it is unlikely he was working alone. Moreover there are stylistic and technical similarities between the early work of Stradivari and Francesco Rugeri. It is possible that at that time there were many connections between the makers working in the different shops in Cremona.

Francesco Rugeri’s labels always use the family nickname ‘il Per’. Photo: courtesy Carlo Chiesa

Starting from the late 1660s, the Rugeri family is referenced in church and civil records with the nickname ‘il Per’. The meaning is unknown, but the nickname probably originated from a need to distinguish this branch of the Rugeri family from another that was active in the same area. Whatever the reason, it appears that often this nickname was even more important than the name itself. In all the labels that I am aware of the name Rugeri is accompanied by the phrase ‘detto il Per’ (‘called the Per’). And in some documents the Rugeri name is missing altogether and the family member is listed simply using ‘Peri’ as a surname.

In the 1670s and 80s the Rugeri workshop was probably an industrious place for the production of instruments, with the mature Francesco increasingly assisted by his four children. With so much youthful manpower, it is no surprise that the workshop was particularly active in making cellos. Their connection with the Amati family was evidently still strong, since in 1689 a grandson of Francesco was baptised and the godfather was Girolamo Amati II, who had led the family workshop since his father’s demise in 1684.