Almost all Stradivari and Guarneri instruments have a nickname. Sometimes these come from a famous musician who played the instrument – for example, the “Alard”, the “Vieuxtemps”, the “Ole Bull” or the “Kreisler” – or from a famous collector – the “Baron Knoop”, the “Betts” or the “Lady Blunt”. Sometimes the name emerges owing to circumstances and fate: the “Messiah” which was promised and never arrived; the “Pucelle” which was pure and untouched; the “Chant du Cygne”, which was one of Stradivari’s last works.

The 1714 ‘da Vinci’ was baptised by this name in 1923.

But it is rare to know the exact moment at which a violin acquired its nickname. In the case of the “da Vinci’, there was previously much speculation as to why it was named after the famous Renaissance artist who died two centuries before the violin was made. In Ernest Doring’s 1945 catalog of Stradivari instruments, How Many Strads?, he suggested that the “title probably originated in its richness of appearance, likened to a masterpiece of the celebrated Italian artist.”[1] In 1974 Sotheby’s offered a similar explanation: “The title ‘da Vinci’ is of course the result of the comparison between the rich appearance of this violin and the work of the celebrated Italian Master.”[2]

There was previously much speculation as to why it was named after the famous Renaissance artist who died two centuries before the violin was made.

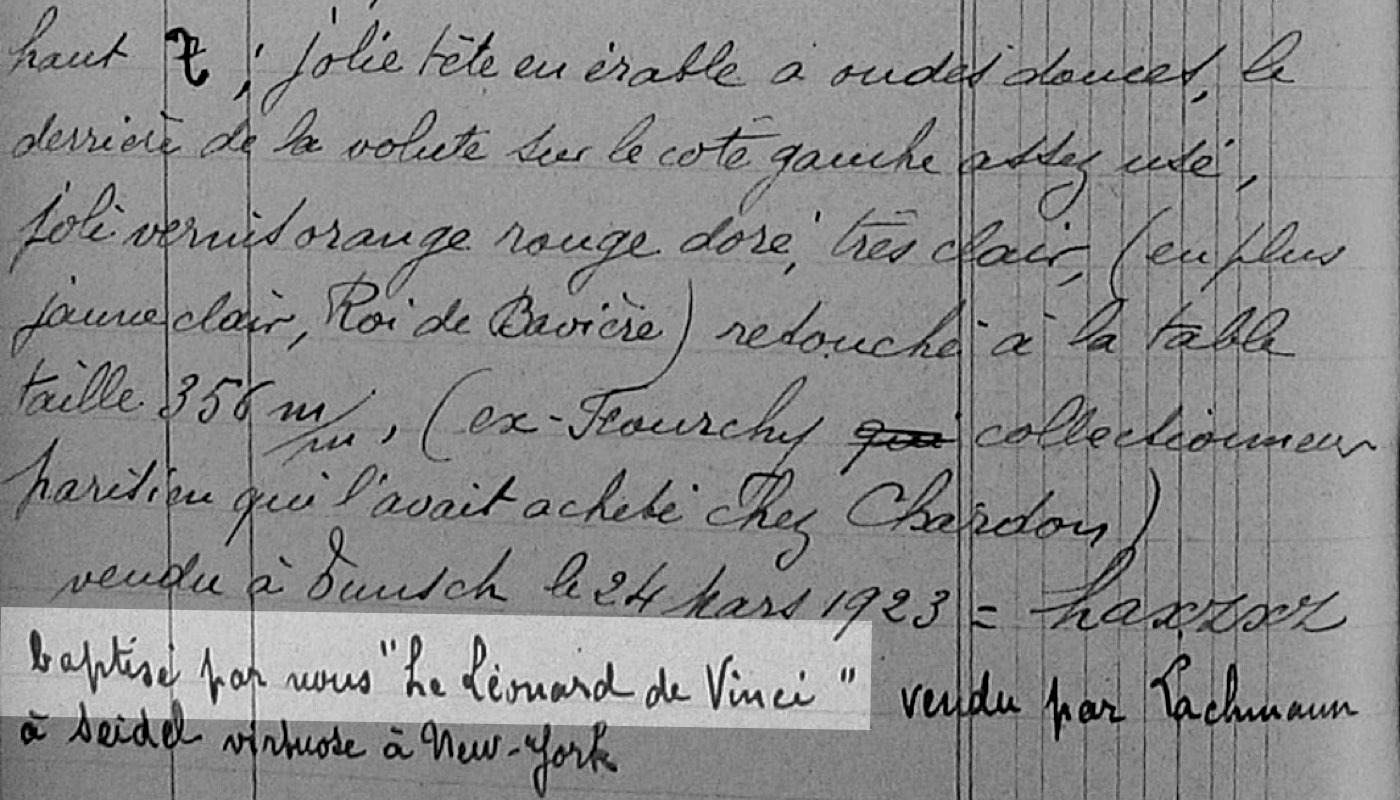

As romantic as that sounds, the true explanation is slightly more prosaic. In the Sales Ledger of Caressa & Français, the handwritten journal of the instruments which were handled by that firm[3], we discovered that it was Albert Caressa who baptized this violin the ‘da Vinci’ in 1923. At the bottom of page 208 after a physical description of the violin and a note that it was sold on March 24, 1923, we find the annotation, “baptisé par nous ‘Le Léonard de Vinci’ (baptized by us ‘the Leonardo da Vinci.’)”[4]

Page 208 from the Jacques Français transcription of the Sales Ledgers of Gand, Bernardel, Caressa & Français preserved in the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution.

And equally interesting is the discovery that this wasn’t the only violin that Caressa baptized after a Renaissance artist. Both the 1718 ‘Michelangelo’ and the 1715 ‘Titian’ also acquired their epithets in Paris in around 1920-1923. In fact, the history of the 1715 ‘Titian’ closely mirrors that of the ‘da Vinci’. In 1922 Caressa & Français sold the ‘Titian’ to the same man in Berlin who bought the ‘da Vinci’, Charles Tunsch, who then sold it to Efram Zimbalist in America. In the Sale Ledgers, Albert Caressa notes that the violin “devenu le Titian (became the Titian)”.[5]

From left to right: the 1715 ‘Titian’, the 1714 ‘da Vinci’ and the 1718 ‘Michelangelo’ Stradivari. All three received their nicknames in Paris in the 1920s.

The ‘da Vinci, ex-Seidel’ will be sold at auction on June 9, 2022. With inquiries, please contact davinci@tarisio.com.

Notes

[1] Doring, Ernest. How Many Strads? 1954. P. 169.

[2] Sothebys. Fine Musical Instruments. London. November 21, 1974.

[3] A handwritten transcription of the Caressa & Français Sales Ledgers is preserved in the Jacques Français Rare Violins, Inc. Photographic Archive and Business Records at the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution.

[4] Caressa & Français Sales Ledgers. Jacques Français Rare Violins, Inc. Photographic Archive and Business Records at the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution. Box 55, Folder 2, P. 208.

[5] Caressa & Français Sales Ledgers. Box 55, Folder 2, P. 52.