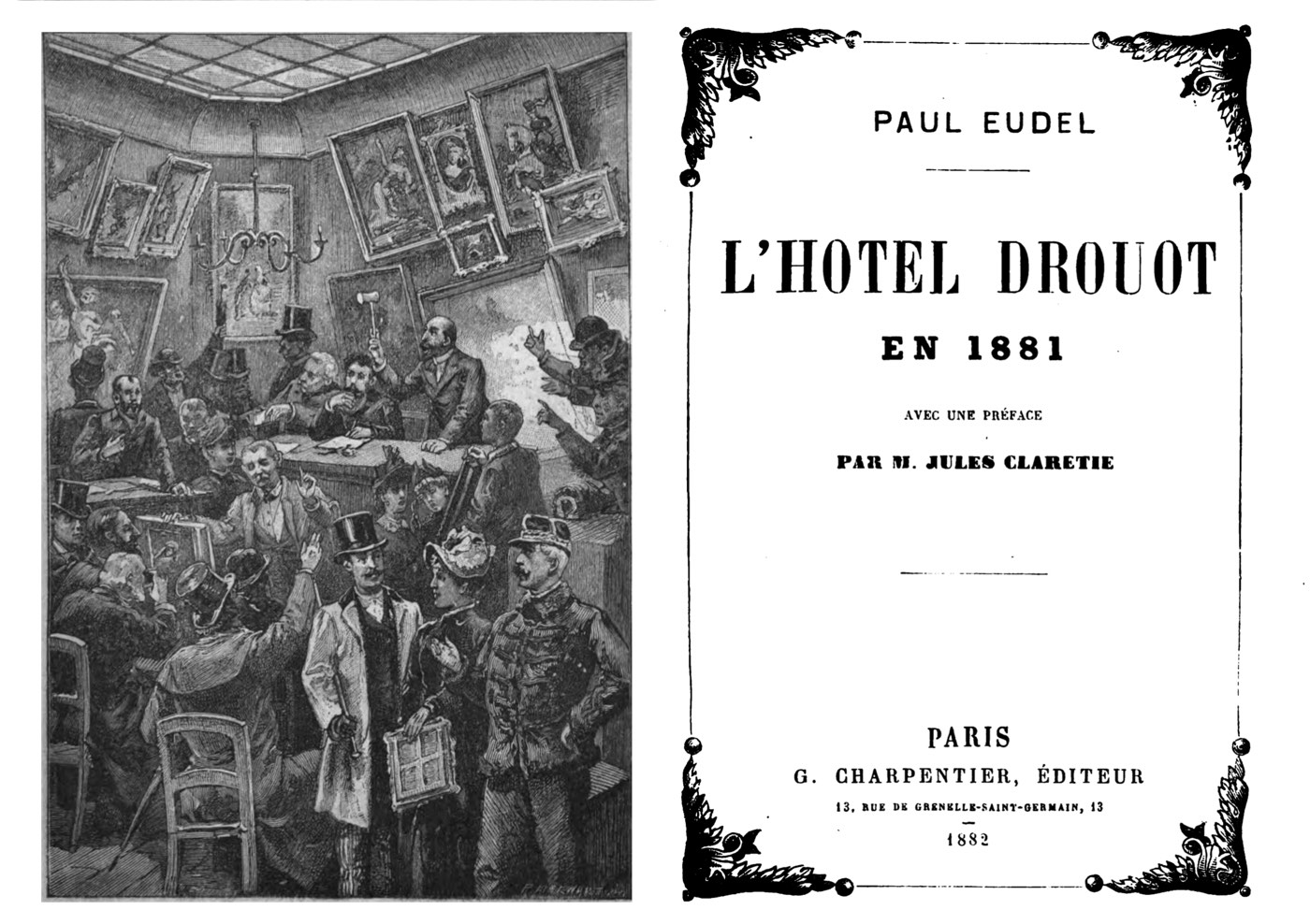

The first public record of the ‘da Vinci’ Stradivari is found in the 1881 auction catalog accompanying the collection of Arthur Foucques d’Emonville (1810–1880). A French botanist and a collector of rare camellias, d’Emonville was also a passionate collector of musical instruments. Upon his death his collection was sold at auction on July 22, 1881 in salle n° 4 of the Hôtel Drouot in Paris. The ‘da Vinci’ – not yet known by that name – sold for 4,600 francs. D’Emonville’s Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ sold for 2,020 francs.

The frontispiece and title page of the L’Hotel Drouot en 1881, a review of the year’s sales at the Parisian auction venue.[1]

A romantic fervor for celebrity violinists and their instruments had swept the continent a half-century earlier and newly minted industrial barons jockeyed with gentry for a chance to own an instrument from the mythical Cremona.

The buyer at the 1881 auction was an agent acting on behalf of the Vicomte Frédéric de Janzé (1817–1900).[3] The Vicomte de Janzé was a noted collector of antiquities and of Italian violins and he was the owner of an estate known as the Pavillon de Musique in Louveciennes, a short distance outside of Paris on the Seine. He had previously acquired four other important instruments at the 1857 Christie’s auction of the James Goding collection in London: the ‘MacDonald’ Stradivari viola, the ‘Jupiter’ Stradivari violin, the ‘King’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ and a Stradivari cello.[4]

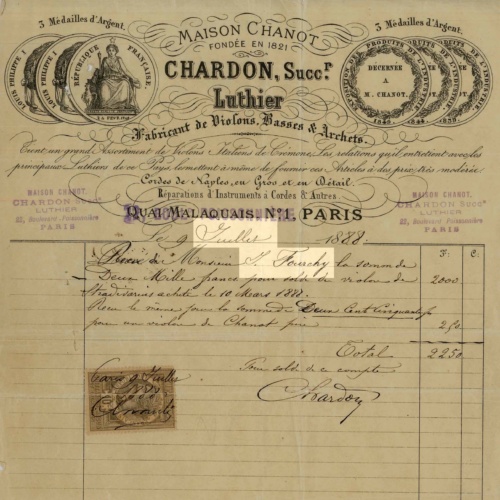

The Chardon receipt from July 9, 1888. Note that the “J” of Juillet is the same as “J. Fourchy.”

In 1888 the ‘da Vinci’ was sold by the Paris dealer Joseph Chardon for 12,000 francs to Antoine Jacques Fourchy (1860–1930), a notaire and an amateur violinist from a family of Parisian lawyers.[5] Fourchy and his wife Hortense Valpinçon were friendly with Edgar Degas and a part of Paris’s avant-garde. Fourchy is elsewhere referred to as a “collectionneur”[6] and the receipt from Chardon shows that he paid for the ‘da Vinci’ by trading a Stainer, a Tecchler and a Vuillaume cello in part-exchange together with 8,800 francs.[7] The ‘da Vinci’ was also not Fourchy’s only business with Chardon; a year later he bought the 1738 ‘Kemp’ Guarneri.

Jacques Fourchy (right) and his wife Hortense Valpinçon with Edgar Degas in c. 1900 at the Valpinçon chateau at Menil-Hubert, Normandy.

Three decades later the ‘da Vinci’ reappeared in Paris, this time at the shop of Caressa & Français. The Caressa & Français certificate, made out to Charles Tunsch in Berlin, was dated May 10, 1914. But the Caressa & Français Sales Ledger clearly states that the violin was sold to Tunsch on March 24, 1923. Tunsch was, for all intents and purposes, a dealer and financier. Alfred Hill noted that he was a close associate of Caressa and actively engaged in investing in instruments destined for America.[8] Caressa described him as an associate of the Berlin dealer, Eric Lachmann.[9] We know of Tunsch’s involvement in three other instrument purchases besides the ‘da Vinci’ and in all four instances, the instrument was sent straight away to America and quickly sold. Anticipating that he would soon be reselling the ‘da Vinci’, Tunsch might have asked for the certificate to be back-dated. It would be to his advantage to show that the violin had been purchased ten years earlier.

We know of Tunsch’s involvement in three other instrument purchases besides the ‘da Vinci’ and in all four instances, the instrument was sent straight away to America and quickly sold.

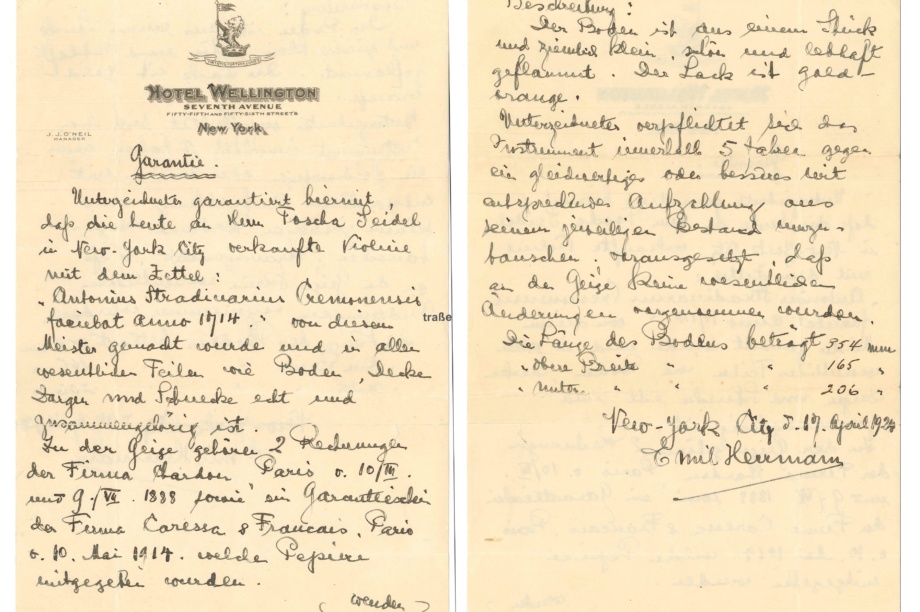

Tunsch had a fruitful association with another Berlin dealer, Emil Herrmann. In 1923 Herrmann and his wife Kira emigrated from Berlin to the United States. One of his first important deals was the sale of the ‘da Vinci’ to the violin virtuoso, Toscha Seidel, who had also recently arrived in New York.. In fact it seems that Herrmann’s premises next to Carnegie Hall at 148 West 57th Street were not yet fully operational by the time Seidel bought the ‘da Vinci’ as Herrmann’s guarantee for the sale is written out longhand, in German, on stationery from the Hotel Wellington on 7th Avenue.

Emil Herrmann gave a handwritten “Garantie” for the ‘da Vinci’ written in German on stationery from the Hotel Wellington on 7th Avenue.

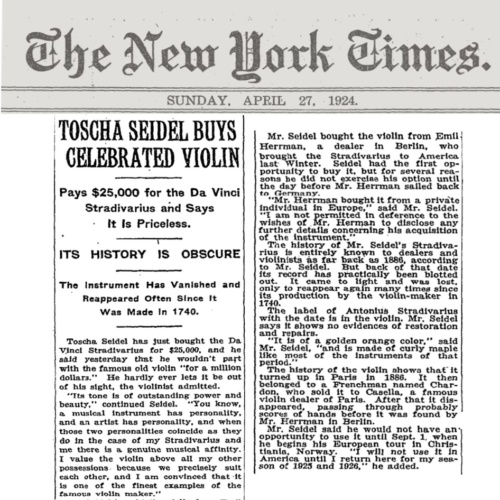

The impromptu nature of the sale didn’t stop it from becoming big news. On April 27, 1924 The New York Times announced on its front page that Toscha Seidel had bought the ‘da Vinci’ Stradivari for $25,000 and that he wouldn’t part with it “for a million dollars.” Seidel was quoted as saying,

You know, a musical instrument has personality, and an artist has personality, and when those two personalities coincide as they do in the case of my Stradivarius and me there is a genuine musical affinity. I value the violin above all my other possessions because we precisely suit each other, and I am convinced it is one of the finest examples of the famous violin maker.[10]

Seidel’s purchase of the ‘da Vinci’ made the front page of The New York Times on April 27, 1924.

Unbeknownst to the readers of the Times, Seidel’s search for the perfect violin had lasted over a year and spanned several continents. Already in January of 1923 he had “fallen in love” with the 1733 ‘Des Rosiers’ Stradivari that was offered by Hills through Rudolph Wurlitzer.[11] But in the end, the ‘da Vinci’ won out over all others and became the concert companion of Seidel for nearly forty years.

Toscha Seidel in c. 1920.

In November 1962 Seidel passed away at the age of 62. Arnold Steinhardt, the long-serving first violinist of the Guarneri String Quartet who studied with Seidel, recalls that Seidel’s widow, Estelle called Steinhard’s parents to ask if they would want to buy Toscha’s violin.[12] At the time Steinhardt was the assistant concertmaster in the Cleveland Orchestra under George Szell and the price was too high for his family to consider. Later that year, the ‘da Vinci’ was sold to Muriel Rubin (1917–2014), a violinist from Toronto who studied at the Eastman School of Music and later settled in Los Angeles.[13] Rubin was an active studio musician and a longtime supporter of the Young Musician’s Foundation in LA. Slightly more than a decade after she acquired the ‘da Vinci’ it was sold at auction at Sotheby’s. “It broke her heart to let it go,” recalls her son.[14]

Muriel Rubin in c. 1950 before she acquired the ‘da Vinci, ex-Seidel’.

At the Sotheby’s sale on November 21, 1974 the ‘da Vinci’ sold for £34,000. It was the highlight of the sale and sold for five times the price that another Stradivari violin had sold for at Sotheby’s the month prior.[15] At the time the ‘da Vinci’ was the fourth highest price ever realized at auction.[16]

It was the highlight of the [Sotheby’s] sale and sold for five times the price that another Stradivari violin had sold for at Sotheby’s the month prior.

In 2008 the ‘da Vinci’ was exhibited in the Stradivari exhibition at the Musée Fabre in Montpelier curated by Peter Biddulph and Frédéric Chaudière. The year prior, the violin had been acquired by Mr. Tokuji Munetsugu and became part of the Munetsugu Collection of Nagoya, Japan. Mr. Munetsugu, a passionate enthusiast of classical music, created the successful CoCo Ichibanya chain of Japanese curry-rice restaurants in Japan in 1978. Known affectionately as CoCoICHI, the popular fast-food chain quickly grew to over 1,000 branches throughout Asia. After retiring from the company, Mr. Munetsugu devoted himself to philanthropic efforts centered around classical music. His non-profit organization, Yellow Angel, provides music instruments to schools in the Aichi prefecture. The prestigious Munetsugu Angel Violin Competition attracts talented international young artists and awards the winner of each competition with the loan of an important instrument. The Munetsugu Hall in Nagoya presents several hundred classical concerts per year, making it one of the largest venues for classical music in Japan.[17]

In selecting instruments for the collection, Mr. Munetsugu was advised by Mr. Muneyuki Nakazawa of Nippon Violin in Tokyo. Today, Nakazawa’s son Sota is the Director of Nippon Violin and oversees the Munetsugu collection. Sota Nakazawa says of the ‘da Vinci’ Stradivari, “This exceptional instrument from the great master’s Golden Period is one of the cornerstones of the Munetsugu collection. It was prominently featured in the TOKYO Stradivarius Festival which I curated in 2018.”

The auction on June 9, 2022 marks the first time the ‘da Vinci, ex-Seidel’ has been offered publicly for sale since 1974. We are humbled to have the privilege of finding the next owner and caretaker of this exceptional instrument.

The ‘da Vinci, ex-Seidel’ will be sold at auction on June 9, 2022. With inquiries, please contact davinci@tarisio.com.

Notes

[1] Illustration from the frontispiece to “L’Hotel Drouot en 1881” by Paul Eudel.

[2] Eudel, Paul, L’Hotel Drouot en 1881, Paris, 1882, P. 257-260.

[3] Alfred Hill noted in 1925 that the violin was bought on the Vicomte’s behalf by the dealer Hippolyte Chrétien Silvestre but in 1962 Desmond Hill wrote that it was the dealer Joseph Chardon. The catalog to the sale notes that de Janzé was advised by M. Chouquet, the conservator at the Musée du Conservatoire.

[4] Jean Baptiste Vuillaume had bid on his behalf, charging the Vicomte a fee of 1,000 francs for his service. A facsimile of the receipt is reproduced in “J. B. Vuillaume: Sa Vie et son Oeuvre” by Roger Millant, London, 1972.

[5] Chardon’s receipt dated July 9, 1888 is made out to “Monsieur J. Fourchy.” Antoine Jacques Fourchy, who went by Jacques, had just turned 28. His grandfather Antoine Jules, also a notary, died in 1875. His uncle Emile died in 1878. His father Paul was still alive at the time of this purchase as was his uncle Georges but the initial J on the Chardon invoice strongly suggests the buyer was Antoine Jacques.

[6] The Jacques Français transcription of the Sales Ledgers of Gand, Bernardel, Caressa & Français preserved in the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution. Box 55, Folder 2, P. 208.

[7] Chardon, Joseph Marie. Receipt, Paris, 10 March 1888.

[8] W. E. Hill & Sons Business Records, Unpublished.

[9] Sales Ledgers of Gand, Bernardel, Caressa & Français. Box 55, Folder 2, P. 208.

[10] The New York Times. April 27, 1924, P. 1.

[11] W. E. Hill & Sons Business Records, Unpublished.

[12] Conversation with Arnold Steinhardt, February 12, 2022.

[13] Letter from Desmond Hill to Paul S. Rubin, Muriel’s husband, February 21, 1962.

[14] Correspondence with Jeremy Rubin, January 14, 2022.

[15] The decorated ‘Lioness’ sold for £6,500 on October 24, 1974.

[16] Behind the ‘Lady Blunt’ (1971), the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ (1973) and the ‘Corbett’ (1974).

[17] Read about the Munetsugu Foundation: https://munetsuguhall.com/en/