As detailed by Philip Kass in Violin Making in Turin (1650–1770), the influences on the Piedmont region’s earliest violin makers differed from those elsewhere in Italy. In Piedmont, as in much of the Italian peninsula, there were German luthiers displaced by the ravages of the Thirty Years War (1618–48). Specific to Piedmont, however, were its strong political and cultural ties to France, as the region was under the rule of the House of Savoy. It is therefore not surprising that many 17th- and early 18th-century Piedmontese violins display construction methods that are distinctly non-Italian but instead are common to the Northern European schools. This included setting the ribs into a channel in the back and one-piece necks (‘through necks’) without separate top-blocks.

Among these early Piedmontese violin makers were those working in Turin (the region’s capital). This included the German-born Enrico Cattenar and three Piedmont natives, Fabrizio Senta, Andrea Gatto, and Giovanni Francesco Celoniato. Outside Turin, Spirito Sorsana worked in the town of Cuneo. Meanwhile Gioffredo Cappa appears to have primarily worked in Saluzzo, a small town about 60 miles south of Turin.

Gioffredo Cappa violin made using the Piedmontese inset-ribs method. Photos: courtesy Ingles & Hayday

Although Cappa (c. 1653–1717) is sometimes referred to as a Turin maker, his connection to the city is unclear. There is a violin bearing a possibly original label dated 1697 in Turin; however, there is no other known documentary evidence of his presence in the city. We also know very little about Cappa’s training as a violin maker. Although his instruments do bear a superficial resemblance to the Amati family, speculation that he was a pupil of one of the Amatis does not stand up to closer scrutiny. Not only is there no documentary evidence to support such a conclusion, but also Cappa’s method of construction is different in several substantive ways.

What is definitively known is that Cappa worked for at least part of his life in Saluzzo, where he died in 1717. According to Federico Sacchi, Orazio Roggiero [1] found Cappa’s death record in the Saluzzo archives in the late 19th century: ‘It was only in 1890 that a barrister of Saluzzo, Signor Roggiero succeeded in finding, in the old registers of the parishes of that town, all the dates relating to this violin maker, whose mysterious existence had seemed to baffle Count Cozio’s researches. Giofreddo Cappa was born in the year 1647, and he died at Saluzzo on August 6, 1717. (“Register for the Dead,” vol. v., page 139, in the Archives of the Cathedral.)’ [2]

More recently, Philip Kass also found Cappa’s will ‘Testamento of Maestro Chiafreddo Cappa’, which was written a few days before Cappa died in 1717. An interesting detail is the spelling of Cappa’s given name as Chiaffredo (not Gioffredo), which is the name of the Patron Saint of Saluzzo. Cappa is also listed in the tax records of Saluzzo stating that he lived in the parish of San Bernardo. [3]

There is still some uncertainty about Cappa’s birthdate, however. Kass’s translation of Cappa’s death record is slightly different from that of Sacchi: ‘Jofredus Cappa, age about 70, administered the sacraments, died on the 6th [of August 1717] and was buried on the 7th in the Cathedral.’ [4] Other sources have variously put Cappa’s date of birth at 1644 and 1653. Perhaps further research will yield an exact date.

Fresco of San Chiaffredo, the Patron Saint of Saluzzo, in a votive chapel, Oncino. Image: Wikimedia Commons

In around 1696 Cappa apparently left Saluzzo and headed south to the town of Mondovi (a cello exists with an original Cappa label dated Mondovi 1697). This was probably motivated by the French invasion of Piedmont in the War of Spanish Succession (1696–1713). Cappa’s movements after this are unknown, but legal documents confirm that he returned to Saluzzo no later than 1707. It is certainly possible that Cappa was in Turin during 1697. However, he does not appear in the Turin census of 1706, perhaps due to the Siege of Turin by French-led forces, which devastated the city in that year.

One of the problems in organizing Cappa’s work, and indeed much of the output from the early Piedmont makers, is a lack of original labels. The confusion dates back to at least the mid-18th century, when many labels were presumably removed or changed by the unscrupulous so they could sell them under a more valuable name. Cappa instruments were mostly reinvented as Amatis, although there is one example of a Cappa violin bearing a spurious label of Andrea Guarneri dated 1701 (three years after Guarneri’s death).

‘Your Amati is not an Amati but a Cappa of Saluzzo. Pugnani changed all Cappa’s labels to Amati and you won’t find any Cappa violins with his name’ – Paganini

Nicolò Paganini wrote about the problem of Cappa labels in a letter to his friend, Luigi Germi, dated June 1823: ‘Your Amati is not an Amati but a Cappa of Saluzzo. Pugnani changed all Cappa’s labels to Amati and you won’t find any Cappa violins with his name.’ [5] Gaetano Pugnani was a Turinese violinist, teacher and composer active during the second half of the 18th century. Working at a time when transactions of violin family instruments were generally facilitated by musicians and luthiers, as opposed to a specialist dealer, Pugnani could well have been responsible for changing some of the labels in Cappa violins. However, it is likely that many Cappa labels, along with those of his Turin contemporaries, had already been altered by the time Pugnani was active.

Gaetano Pugnani by an unknown painter, Piedmontese school. Image: courtesy Royal College of Music Museum of Instruments

Count Cozio de Salabue also noted the lack of original Cappa labels, writing in his memoirs: ‘Up until now, it has not been possible to find any of his instruments with original labels. A great number of his instruments, especially the best and oldest ones, were applied with the Amati’s label and sold as such (particularly to foreigners).’ [6] Cozio points out that there were violins bearing Cappa labels with the first name given as either Goffredo or Gioacchino: ‘It was said in Piedmont tradition, that two, or perhaps, more of these Cappa’s worked one after the other. The first of which probably was the only one to be Amati’s pupil.’ [7]

‘[Viotti] usually played and dealt the violins made by this Cappa, and it was not a small business’ – Count Cozio di Salabue

There is no evidence to suggest that there was more than one Cappa nor, as stated previously, any evidence of an apprenticeship in the Amati workshop. However, it does appear that by the late-18th century, fake Cappa labels were being inserted into instruments attributed to the work of Cappa. This was probably at least in part due to a growing appreciation of his instruments. Cozio wrote that Cappa was one of the best imitators of the Amatis and that Cappa violins ‘were greatly valued, especially by people in Holland and England, who paid high prices for these instruments.’ Cozio also noted that Cappa’s work was promoted by the violin virtuoso Giovanni Battista Viotti: ‘[Viotti] usually played and dealt the violins made by this Cappa, and it was not a small business. Viotti’s students also played instruments of this Cappa.’ [8]

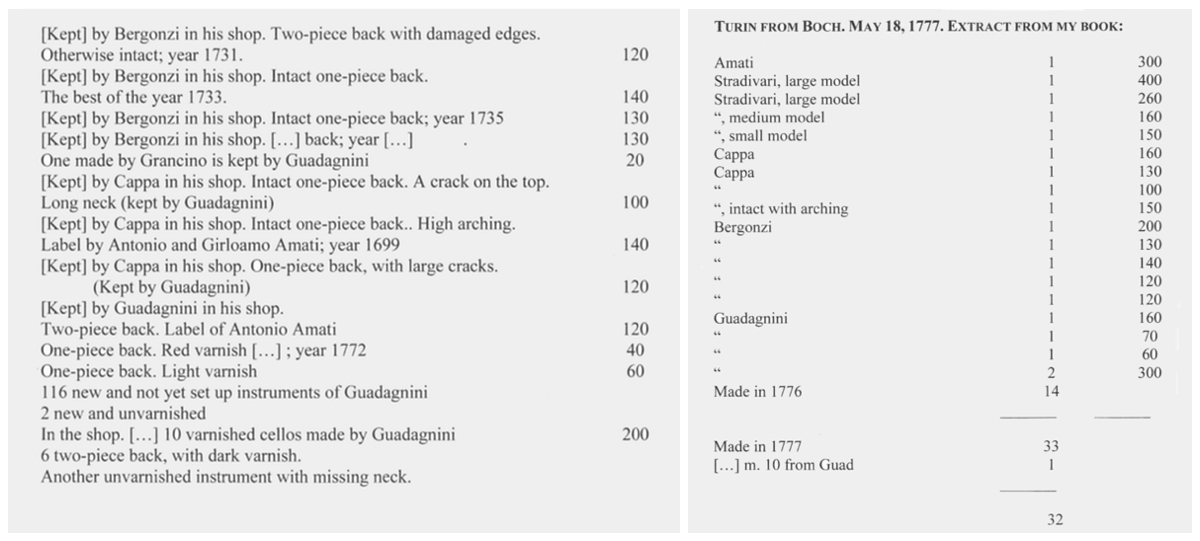

Cappa’s work figured prominently in Cozio’s own business. An inventory of February 1775 lists seven Cappa violins belonging to Cozio that were worked on by G.B. Guadagnini and, in a contract dated May 1779, Guadagnini agreed to fix and sell on behalf of Cozio a Cappa violin for 90 zecchini as well as another ‘unbroken’ one for 90 zecchini. The same letter gives some insight to the relative value of Cappa instruments, mentioning a Grancino violin to be sold for 20 zecchini and a Stradivari violin of medium size to be sold for not less than 120 zecchini. [9] Another inventory of Cozio’s instruments dated May 1777 confirms that he valued Cappa violins almost as highly as other important makers, with the exception of the most valuable examples by Amati and Stradivari. [10]

Inventory lists of Count Cozio’s instruments from 1775 (left) and 1777 (prices in zecchini). Images: Cozio Count memoirs

The lack of original labels and the re-inserting of facsimile labels into 17th- and early-18th-century Piedmontese instruments has complicated the problem of authenticating Cappa’s work. As Cappa had become the best known of the early Piedmont makers, many instruments were relabeled with his name, irrespective of the actual work. This has made Cappa’s alleged output more varied and prolific than it actually is and created confusion about the work of his contemporaries.

Fortunately there is a group of instruments accepted as the work of Gioffredo Cappa that are stylistically and technically very consistent, making identification possible.

With thanks to Philip J. Kass. Part 2 will explore the surviving instruments of Gioffredo Cappa.

Julian Hersh is a cellist, expert and co-founder of Darnton & Hersh Fine Violins in Chicago.

Notes

[1] A collector and dealer of musical instruments, Orazio Roggiero is credited with introducing Annibale Fagnola to violin making.

[2] Sacchi, Federico, Count Cozio di Salabue: Celebrated Violin Collector, Dulan & Co., London, 1898, p. 21.

[3] Kass, Philip J., ‘Modern Historical Research: The Violin as Art’, Journal of the Violin Society of America, vol. XIII, no. 2, p. 19.

[4] Kass, Philip J., ibid, p. 15.

[5] De Courcy, G.I.C., Paganini: The Genoese, University of Oklahoma Press, 1957, p. 223.

[6] Cozio, Count Ignazio Alessandro di Salabue, Memoirs of a Violin Collector, ed. Frazier, B., Gateway Press, Baltimore, 2007, p. 10.

[7] Ibid, p. 16.

[8] Ibid, p. 16.

[9] Ibid, p. 131–132.

[10] Ibid, p. 211–213.