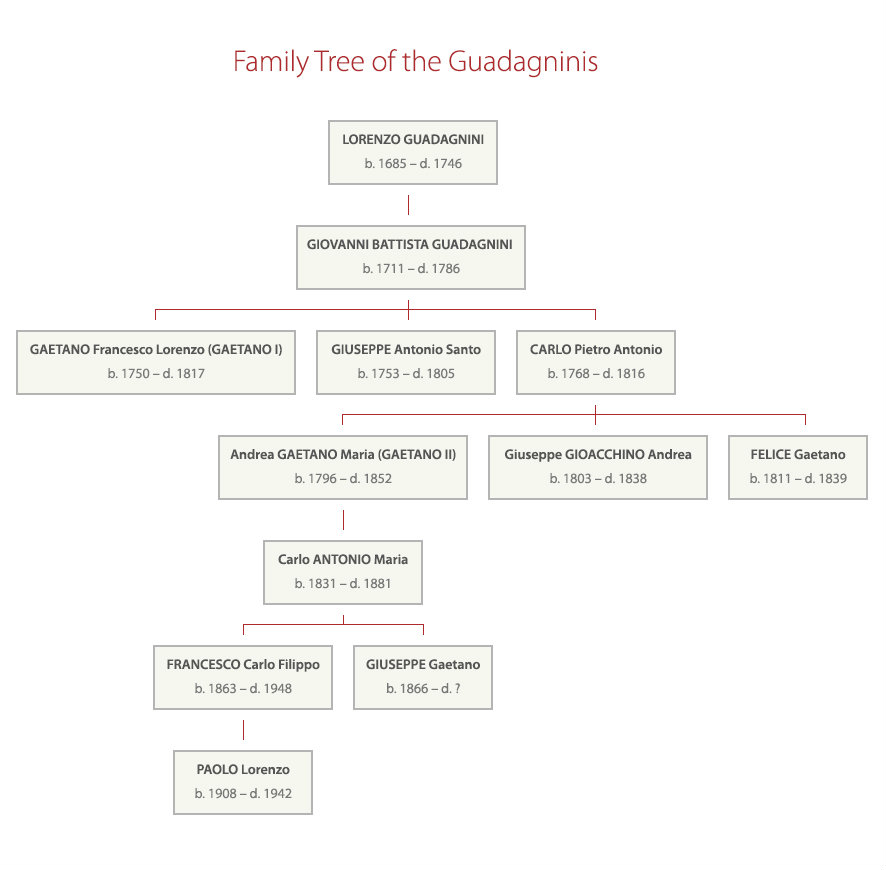

In Part 1 of Violin Making in Turin, I discussed the important early makers of the city and the tradition they established for style and construction. By the later 1700s, like many lutherie traditions in other parts of the Italian peninsula, this was disappearing. In 1770 there was only one violin maker still active in Turin, Giovanni Battista Genova, and even he stopped working altogether shortly thereafter. This was shortly to change, in the form of a newcomer: Giovanni Battista Guadagnini (1711–1786), who was to dominate the city’s violin trade, and whose family continued that domination after his death.

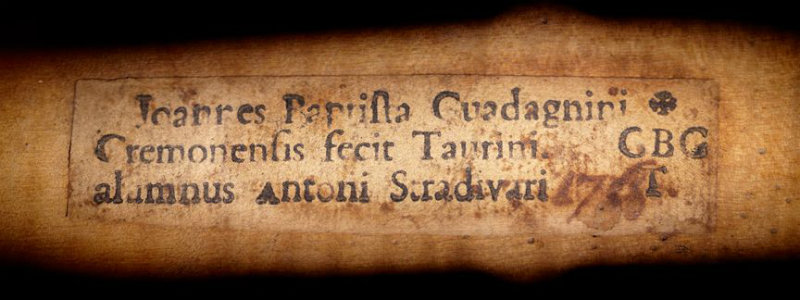

The label of the ‘Huxham’ Guadagnini cello. Photo: Robert Bailey, Tarisio

By early 1771 the financial environment in Parma, then Guadagnini’s home, was growing increasingly uncertain, and it appeared that he was casting about for a new home. In that year’s church census, his son Gaetano was missing; shortly thereafter, Giovanni Battista wrote to the Prime Minister du Tillot and asked for a stipend to go to Turin along with his son, suggesting that Gaetano had visited the city and found fertile ground. Guadagnini was duly granted a sum of money and freed from his obligations, permitting him to make the move.

Guadagnini arrived in Turin some time in 1771 with his whole family in tow (including his pregnant wife, who gave birth to their last child in November of that year). His timing was not ideal. When scouting for a new home, Turin must have seemed perfect: an active musical environment, supported by the king, and a dearth of violin makers. However, the reigning king died in 1773 and his death was followed by a protracted period of mourning, during which time the court’s musical activities were curtailed.

The ‘Salabue’ Guadagnini of 1774 dates from the period of Guadagnini’s agreement with Count Cozio

More photosWhile all this was happening, though, he came into contact with a young nobleman, Ignazio Alessandro Cozio, Count of Salabue, who dreamed of re-establishing the greatness of Italian violin making. Guadagnini, who was now professing to be a student of the Cremonese school, was the perfect vehicle for this dream. Cozio was further inspired when Guadagnini told him that the Stradivari family possessed a number of unsold instruments as well as the tools and forms from Stradivari’s workshop, the only such workshop preserved from the classical period.

The result was Cozio’s acquisition of the Stradivari instruments and workshop contents as well as a contract between the count and Guadagnini, in which Cozio provided wood and other materials to Guadagnini and agreed to buy every instrument he made from them. This agreement lasted from around 1773 until 1776, after which time Guadagnini continued to serve Cozio, but only as a vendor and restorer of instruments.

Guadagnini’s method remained almost entirely within the family; we know of no others from the town who worked with him and thus learned his methods

Guadagnini brought with him the Lombard methods of violin making, based on the Cremonese system; it was the first appearance of this method in Piedmont. In its use of internal molds, it was very much at odds to the now-defunct Turin method of channeled backs and templates. This method remained almost entirely within the family; we know of no others from the town who worked with him and thus learned his methods, and when later makers arrived they worked in an entirely different French-based system using external molds.

Guadagnini’s style on arrival in Turin was a continuation of his Parma work. Indeed, the instruments from his first five years in Turin look much like those of Parma except for the obvious local wood selections (mountain maples in place of the rooty oppio of the Po Valley) and a gold varnish in place of the more subdued browns of the late Parma years. Cozio requested that he use the Stradivari form and Stradivari’s tools, but despite his supposed Cremonese training, Guadagnini continued to follow his old ways. His only apparent concessions were to lower and slightly alter the shape of his arching and to add a black edging to his scrolls in imitation of Stradivari.

Once the contract with Cozio had ended, however, for some reason Guadagnini’s style became much more Stradivari influenced. The inspiration was drawn from Stradivari’s late works, resulting in a Stradivarian model that was heavy in character, with broad, thick corners and edges and a deep purple-red varnish. His distinctive ‘f’, with its oval holes, was replaced by a broad stroke of an ‘f’, essentially after Stradivari, and rounder holes.

The 1783 ‘Maazel’ violin was made towards the end of Guadagnini’s life and shows his switch to a more Stradivari-influenced model. Photos: Robert Bailey, Tarisio

More photosWhen Guadagnini died in 1786 he was succeeded by his sons Gaetano I (1750–1817) and Carlo (1768–1816). They inherited the business in the middle of an economic decline, which had taken hold in Italy during the 18th century, and exports to France further dried up for Turin after the French Revolution in 1789. In Turin and many other towns, violin makers turned to other sorts of instruments to make a living. The generations of Guadagninis after Giovanni Battista became specialists in guitars, and, except for a scant few violins, it is by their guitars that we know them.

In 1796 and again in 1798 Napoleon invaded Piedmont and established control over it and most of Italy. Turin and the entire Kingdom of Sardinia, along with the Republic of Genoa, were annexed to France, remaining a Department until the French retreated in 1814. With French rule came French institutions, including a branch of the Conservatoire de Musique. In turn this brought French violin makers, most notably the merchant–luthier Nicolas Lete-Pillement (1775–1819), who established a workshop just outside the old city walls and was responsible for bringing a number of French luthiers to Turin, not all of whom would later return to France. In this environment the Guadagnini brothers continued to ply their craft, making guitars and mandolins and the very occasional violin.

In 1814, with their empire collapsing, the French abruptly abandoned Turin, and the Sardinian king returned to claim his territories. In the peace following the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, the king was permitted to keep the old Republic of Genoa, which the French had incorporated into their territory, thus bringing an end to centuries of Genoese independence. This proved a difficult issue for both Turin and Genoa, but it resulted in a more consistent exchange of instrument making and makers between the two cities, which up until then had been entirely different in their traditions.

As the economy began to recover, the Guadagnini family faced a tragedy when Carlo, the younger of the two brothers, died in 1816. His elder brother, Gaetano I, had no children, and succession most logically should have been through Carlo’s family. Thus it was that Gaetano I made a contract with his brother’s family so that the business would be inherited by Carlo’s eldest son Gaetano II (1796–1852), who was only 20 years old but had learnt his trade in the family workshop. He took full control the following year, when Gaetano I died.

On Gaetano II’s death in 1852 an extensive inventory revealed him to be a partner of the Vuillaume family in Paris

Under Gaetano II the business began to prosper. He remained primarily a maker of guitars, but there were occasional violins and after the 1820s these took advantage of French methods (and probably also French labor, in the form of employees trained in French workshops). This connection is implicit, rather than documented: it comes in the shape of Gaetano Guadagnini violins from the 1830s onwards using an external form very similar to that used by the French and by the Guadagninis’ neighbors, Pressenda and Alexandre D’Espine.

Gaetano II received important patronage from the royal family, particularly the duke of Genoa, the son of the king of Sardinia, and had a contract to provide repairs and services to the fledgling Philharmonic Society. On his death in 1852 an extensive inventory revealed him to be a steady business client of and partner to the Vuillaume family in Paris.

An 1860 violin by Antonio Guadagnini; after inheriting the business aged 21, he proved to be an astute businessman

More photosFrom 1829 Turin began to hold expositions to promote manufacturing and trade. Gaetano II entered guitars and received a copper medal. Two years earlier he had been one of the first Turin makers to compete outside his territory when he submitted guitars to the 1827 Paris Exposition. He continued to exhibit in the subsequent Turin expositions of 1832, 1838, 1844 and 1850, receiving similar honors at each. In 1838 he had an unexpected competitor: his half-brother Felice (1811–1839). Felice’s mother, as Carlo’s widow, also owned part of the business; when Gaetano II bought out her share in 1828, she used the proceeds to set up Felice as a business rival. Felice’s violin was well regarded by the judges, but any chance of developing his enterprise was cut off by his early death the following year.

The Guadagnini lineage thus continued with Gaetano II’s son Antonio (1831–1881). Antonio inherited the business at 21 but his age was hardly a drawback, for he was probably the most successful businessman in the family. He took advantage of local talent and while his production included many guitars, he had an increased trade in violins. He employed many of the finest craftsmen of his age, including Enrico Marchetti, the brothers Enrico and Pietro Melegari, and a French Savoyard named Maurice Mermillot, who worked for him for several years before returning to Paris to establish his own business. Antonio also continued his father’s trade with the Vuillaume family and was a debtor to Nicolas Vuillaume at the time of the latter’s death in 1877.

Antonio died aged 50 on New Year’s Eve 1881, leaving the business to his widow and his 18-year-old son Francesco (1863–1948). It continued under Antonio’s name, as was the custom, and for 12 years Francesco worked for his mother. There are indications that this relationship was not always smooth, and in 1893 Francesco and his brother left for Rome. However, when his mother died the following year, Francesco returned to Turin and took over the business, renaming it in the process.

By this time the violin trade had changed significantly. Antonio’s only rival had been the maker and dealer Benedetto Gioffredo, called Rinaldi. Rinaldi, like Guadagnini, had hired numerous makers to work for him. By the end of the century, many of these makers had established their own shops. Francesco, as a violin maker, had to compete against Enrico Melegari, Enrico Marchetti, Giorgio Gatti and Romano Marengo Rinaldi, Benedetto’s successor, and later also Carlo Giuseppe Oddone and Annibale Fagnola. He continued as his father and grandfather had, though, as a maker of violins and guitars. There is a certain amount of his later production that suggests the use of French labor or even unfinished French instruments, but mostly it is recognizably Francesco’s work, albeit in the Fagnola-like Turin style more in the character of his times.

Francesco’s son Paolo (1906–1943) would have continued the lineage, but his death during World War II and the family shop’s destruction during bombing raids finally brought the six-generation Guadagnini dynasty to a close.

Philip J. Kass is a respected expert on classical violin making and has contributed extensively to the Journal of the Violin Society of America, The Strad magazine and the New Grove Dictionary of Music. In part 3 he analyses the Turin makers of the 19th century, including Pressenda and Rocca.