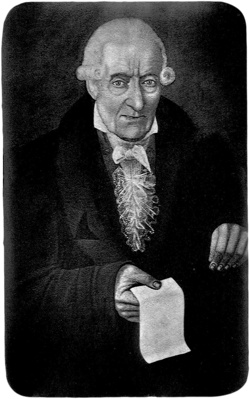

Count Ignazio Alessandro Cozio di Salabue (1755–1840)

Count Cozio di Salabue is a singularly important figure in the story of the violin; the man who first defined the role of the violin connoisseur, dealer and expert, and the first to write a reasoned account of the violin and its greatest makers in Italy. A large part of this account was published under the title ‘Carteggio’ (‘Papers’) in 1950 by Renzo Brachetta, and a much-needed English translation was published by Brandon Frazier in 2007. Count Cozio’s Carteggio notes remain a vitally important source for our present knowledge of the lives and status of many great makers and the history of many highly significant individual instruments. It is the first historical record, written within a half-century of the demise of the major Italian schools, but with contributions from several significant professional makers of the later period, including Giovanni Battista Guadagnini.

On the other hand, the notes and accounts within the Cozio Carteggio have to be handled carefully and interpreted with some caution. One of the problems is the language he used; his Italian is strongly flavored with his native Piemontese dialect, which is still difficult to translate, making some of his technical descriptions incomprehensible. As with any historical document, the author’s viewpoint is personal and different to ours. Things that were obvious to Cozio may have seemed to him not worth writing about, but points of interest have changed. Although he was possibly the first to take note of measurements and other objective, technical aspects that separated one maker from another and provided clues to their training and development, these details as he drafted them are not infallible, and his results are often difficult to render into understandable data. However, the more we delve into his life and work, the more clarity we can gain from his documents, and the more valuable his work becomes.

He was born Alessandro Ignazio Alessandro Cozio di Salabue in Casale Monferrato on March 14, 1755. The family residence in Salabue was nearby, in the hills of Piedmont. His family was a distinguished one. He was the only son of Carlo, Conte di Salabue and Terregia, and his wife the Marchioness Taddea Balbani. Carlo was a cultivated man, a celebrated chess player who wrote two large volumes about the game that still have considerable importance in the history of chess. He was also a violinist whose Amati is said to have first spurred Cozio’s interest in the instrument.

Count Cozio’s villa in Salabue (reproduced courtesy of Edizioni Il Salabue)

At the age of 16 Cozio was sent to the Military Academy in Turin, a course that evidently did not greatly appeal to him, for within a few years he had met and come to a business arrangement with Giovanni Battista Guadagnini. Guadagnini fortuitously arrived in Turin at the same time as Cozio, in 1771; the violin maker was then aged 60 and had just left Parma. Cozio was still only 16, but he quickly became obsessed with the craft. Aged 18 he arranged a contract with Guadagnini to buy the entire output of his workshop. This also marked the beginning of Cozio’s association with Giovanni Anselmi Briatta, who operated as his business agent thereafter.

Cozio seems to have been anxious to learn what he could about the Amatis and Antonio Stradivari. This in itself is telling; the Cremonese maestro had been dead little more than 35 years, yet there seems to have been little reliable information that Cozio could readily obtain. Guadagnini himself made a false claim to have been Stradivari’s pupil, but nonetheless he was able to assist Cozio in brokering the most important deal of his life: the acquisition of all the remaining contents of the Stradivari workshop from Antonio’s surviving son Paolo in 1775.

Stradivari had been dead little more than 35 years, yet there seems to have been little reliable information that Cozio could readily obtain

This was a great coup for Cozio. In a single deal, completed the following year with Antonio Stradivari, the son of Paolo who died in the interim, he obtained not only ten finished and unplayed instruments including the almost mythical ‘Messie’ of 1716, but also all the tools, templates and drawings remaining in the workshop, which gave Cozio great insight into the working methods of the greatest violin maker the world has seen. Furthermore, Cozio’s private inventories of stock provide a great insight into the demand and importance of historical makers, an interest which has continued to develop far beyond even Cozio’s farsighted notions. As he himself stated, his purpose was ‘to discover if it is possible to understand the secrets of this difficult art so that they can again be used in Italy’.

In the earliest existing inventory, dated June 18, 1775, Cozio lists Amati, Stradivari, Guarneri, Grancino and Cappa instruments, alongside his new Guadagninis and a Stainer. In later lists, Rugeri and Bergonzi appear, plus other minor makers. An interest, somewhat out of proportion to modern dealers perhaps, in Gioffredo Cappa is significant. Cozio attaches a great importance to this Piedmont maker and acquired many examples of his work.

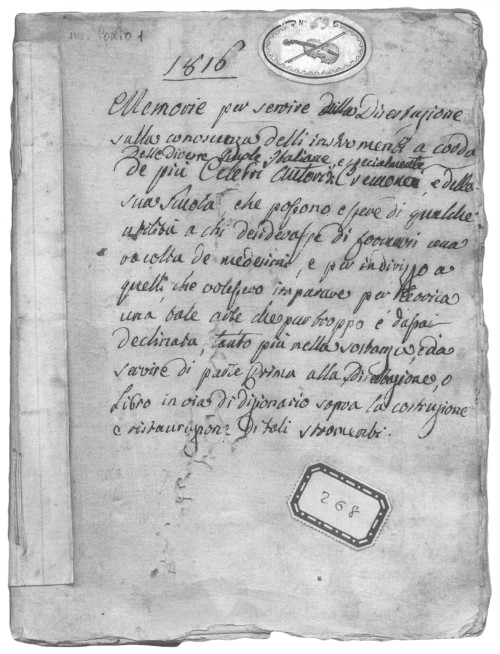

The ‘Carteggio’ manuscript

Cozio continued to correspond with Guadagnini, developing contacts with other makers through him, and attempting to push Guadagnini’s own style closer to that of Stradivari, an idea to which Guadagnini was somewhat resistant. Nevertheless, a change of style in this direction is notable in his late Turin work. The relationship between the Count and the violin maker lasted only a few years, and after 1780 there was little correspondence between the two. Cozio’s notes later describe Guadagnini as ‘conceited, individualistic and stubborn’. Cozio had, however, acquired more than 50 Guadagnini instruments to add to his already impressive collection by the time of Guadagnini’s death in 1786.

Around that time (c. 1780) Cozio’s father died, which presumably released more financial resources to the young Count, but his interest in the violin seems to have begun to wane. Perhaps the management of the family home became too great a responsibility for a time, but in 1796 the market between France and Piedmont was opened, thanks to the creation of the Republic of Alba, a ‘client state’ of the new French Republic. Previously Piedmont had been part of the Kingdom of Sardinia, but now the prospect of trade with France created new possibilities for Cozio and he was drawn back into violin dealing. This became an active pursuit from 1800, and in 1801 he drew up a new inventory of stock. In here we discover a new agent, Antonio Monzino of Milan, who became an active negotiator on his behalf. Cozio moved all his stock and collection to Milan for storage with a friend, Carlo Carli, and for a while devoted his energies to investigating the history of his own patrimony, the towns of Casale and Monferrato.

Cozio was energetic in his buying and selling of instruments, but the detailed notes he took are perhaps his most valuable legacy

From 1801 to 1816, throughout the turmoil of the Napoleonic period, Cozio was energetic in his buying and selling of instruments, but the detailed notes he took are perhaps his most valuable legacy. He obviously had a deep and passionate interest in the craft of the violin and the artistry of its great makers. Unfortunately his notation is difficult to interpret and often contradictory. The writing is obviously personal in nature, intended as simple aide-memoirs for his own benefit, and sometimes opaque to the casual reader. His system of measurement, using now obsolete units of ‘parti, linea, punti and pollici’, can be successfully rendered into modern data, but they are often either illogical, impossible or somewhat inaccurate.

One of the difficulties in recreating the history of the ‘Messie’ Stradivari of 1716 is that Cozio’s description of the ‘most beautiful and large violin made by Antonio Stradivari in 1716’, which is assumed to be the ‘Messie’, is supplemented with measurements that can only be those of a Long Pattern instrument, which Stradivari ceased making in 1700. It seems likely, however, that these are the errors of a man making hurried notes for his own purposes, rather than the diligent analyses of an academic writing for public consumption.

The ‘Kreisler, Perlman’ Bergonzi of c. 1735. Alarmingly, Cozio instructed his luthiers to cut back the corners of the Bergonzis in his collection

More photosThe Cozio Carteggio also betray an attitude to these now revered instruments that strikes alarm in the modern reader. He criticises his fine Bergonzi violins for having corners that are too long, and he simply instructs his luthiers, the Mantegazzas in Milan, to cut them back. He also required them to regraduate instruments, Stradivaris not excluded, whose thickness he considered excessive. The results of this apparent butchery can be identified in the instruments today.

But this attitude was common. Although Stradivari and the other great makers were respected, there was not yet a prevailing attitude that these instruments may never be bettered. This is revealed repeatedly in the published tracts on violin making of that time by Bagatella and Marchi (who was a correspondent of Cozio’s), and also in the notorious episodes of Don Ascenzio and Ortega in Spain, made common knowledge by the Hills in their seminal work on Stradivari. The luthiers of the time, and Cozio himself, saw the great makers as inspirational, but not naturally superior to themselves in ability or insight, and certainly not beyond improvement. It was in this period that the Mantegazzas changed and modernized the necks of older violins on a large scale. This would be an outrageous act for a modern restorer, but at the time it was an act of pragmatism.

Cozio’s understanding of the Cremonese school was patchy, but many of his observations have survived the test of time

The Mantegazzas were important in Cozio’s career. As well as carrying out repair work for him, they advised him on authenticity of instruments and gave him information on other makers. Cozio seems never to have visited Cremona personally, but relied on people like the Mantegazzas, his agents Briatta and Monzino, and other makers including Tomasso Balestrieri, but also on aides including a fellow nobleman, Alessandro Maggi, and the Cremonese historian Vincenzo Lancetti for information. His understanding of the Cremonese school was patchy, but many of his observations have survived the test of time; re-examining his notes in the light of modern research is fundamentally important and always relevant. More interesting to Cozio was the history of his own region and the makers of Turin, hence his lasting interest in Guadagnini and Cappa.

In 1816 he began writing his History of the Violin. This, unlike his inventory notes, was obviously intended for publication and is carefully written. It displays, in the main, a thorough and practical understanding of the development of the various Italian schools of making, much first-hand observation that continues to provide important guidance to modern research, and a genuine knowledge of the principles of making and adjustment, with much good advice given for makers. This intense burst of activity lasted until 1827, when at the age of 72, and having been intensely involved with the violin and its history for over 50 years, he seems to have gone into retirement. He died in 1840, aged 85.

The ‘Simpson’ Guadagnini of c. 1777. The Count’s relations with Guadagnini were difficult and he described the maker as ‘conceited, individualistic and stubborn’

More photosIt was only then that his central collection was finally dispersed. The main buyer was Luigi Tarisio, another Piedmontese, who was the natural successor to Cozio; a man from a totally different background, an uneducated farmer who nevertheless shared his passion for great violins to the point of obsession. Negotiations with Tarisio began before Cozio’s death in 1839 but were not completed for another six years, when another agent, Giuseppe Carli, finally settled with Tarisio on behalf of the Count’s daughter, Matilde.

The end was by no means tidy, however. Matilde herself died shortly thereafter and Carli died in 1841. The hugely important Stradivari forms, the series of moulds he used to construct his violins, still remained in the family. They and several more violins were inherited by a cousin, the Marquis Rolando Dalla Valle. The collection of workshop materials stayed in this family until purchased by the violin maker Giuseppe Fiorini in 1920; it was Fiorini who finally gave the collection to the City of Cremona, where it now occupies a central position in the Museo del Violino.

In the middle of negotiations with Guadagnini we suddenly find Paolo Stradivari offering to send him some sweet pickle

The Count’s various papers are full of interest. A lot of the content is very dry and business-like, but in the middle of negotiations with Guadagnini we suddenly find Paolo Stradivari offering to send him some sweet pickle. In other correspondence with the rather long-winded Bolognese violin maker G.A. Marchi, Cozio seizes on a mysterious Russian philosopher whom Marchi claims taught him the secrets of his craft. Marchi rebuffs his repeated attempts to identify the philosopher, and we are left with the strong impression that it is all a fantasy. Cozio’s assessments of the various violin makers can be surprising. Rogeri of Brescia is ‘not a good maker’, Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ (although not known to Cozio by that soubriquet) is only of the ‘third category’ of makers, and Francesco Rugeri’s cellos are also judged ‘third class’. Stradivari’s varnish comes in for criticism: it ‘does not stick properly to the wood… will not last as many centuries as… the Amatis’.

Cozio had no preconceptions. He was an explorer of the unknown, and wrote plainly of what he saw and experienced. His responses are honest and unfettered by the modern spiralling of values and reputations. In some opinions he has proved misguided, but generally he is a reliable witness. Within the pages are important revelations, such as an insistence, despite numerous contradictory recipes offered from various sources, that Stradivari based his varnish on boiled walnut oil – a conclusion now supported by laboratory analysis. Various anonymous English Lords come and go in search of Cremonese instruments – Cozio even had a sales list written in English for their benefit – but what he repeats again and again is that the foreign buyers coming to Cremona are looking chiefly for Stradivaris, and there are none left to be had.

Cozio fully understood the exceptional nature of Stradivari’s career, even though within Italy he was still largely underestimated. His fame had already spread widely abroad, and this was where Cozio’s own market lay. But his passion for Stradivari was genuine and his pride in his own two ‘masterpieces’ bought from Paolo Stradivari, the 1716 and 1736 violins, is reiterated throughout his writing. They are, he says, ‘the ideal models for the violin maker’, above and beyond any of the other instruments and makers he describes.

There is a lot of varied information – even at one point instructions for how to make sandpaper

So apart from the historical trail of specific instruments such as the ‘Messie’ through his notes and inventories, there is a lot of varied information – even at one point instructions for how to make sandpaper. Cozio has an easy familiarity with the different patterns used by Stradivari, having possession of the forms and designs, and he was able to apply them to the instruments themselves. He assigns form letters to many of the Stradivari violins he discusses – ‘P’, ‘PG’, ‘G’ and so forth – something that today’s experts were unable to do until fairly recently. The Hills plainly had no knowledge of this, and Stradivari’s coded forms remained a mystery to them, leading to one of the very few false notes in their 1902 biography of him, when they misinterpreted the ‘PG’ inscription observed in pegbox mortices as ‘PS’, for Paolo Stradivari. Cozio would have known precisely what the letters meant, one hundred years earlier. In 1902, however, all this information was held by his descendant the Marquis Dalla Valle in Turin, unpublished, untranslated and generally unknown. Cozio di Salabue is the missing link between modern expertise and the everyday activity of the great Italian violin makers, and his ‘Carteggio’ is a Rosetta Stone of the history of violin making.

John Dilworth is a maker, writer and expert. He has written extensively about fine instruments and their makers, and is a co-author of ‘The British Violin’, ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ and ‘The Voller Brothers’ among other books.

Tarisio sold an original letter by Count Cozio in June 2017.