As the lives of other violin makers reveal themselves under academic scrutiny in archives and geneaologies, Antonio Stradivari remains stubbornly absent. We still don’t know exactly when or where he was born, and we do not know how he learned his trade.

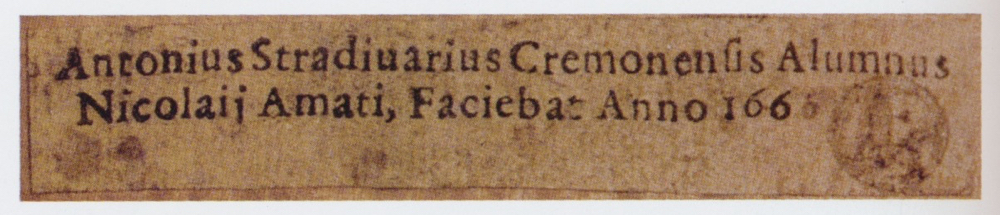

Tradition says that Stradivari was a pupil of Nicolò Amati. In some ways this makes perfect sense. The timing is right and the earliest sources – Arisi, Cozio di Salabue, Lancetti and Fetis – all followed this line. There is just one piece of real evidence, however: the famous ‘Alumnus Amati’ label of 1666, which the Hills show in their 1902 Stradivari book. This label apparently confirms what observation tells us: that Stradivari made violins in the style of Amati, that his workmanship was the equal of Amati, and that therefore he trained with Amati. But when you have a tangle you don’t pull on the first loose thread; it just makes everything tighter.

The label of the 1666 ‘Serdet’ Stradivari famously states that Stradivari was an Amati pupil. Photo: Beare Violins Ltd

In the Cremona archives there seems to be no trace of Stradivari’s presence in the Amati shop. His name does not figure on the lists of Amati’s apprentices. And why does the Amati name appear only once on Stradivari’s labels? The ‘Alumnus’ label is quite different in form to any others and has three digits of the date printed. He obviously intended to use it many times, but it remains unique. The next known label, from the 1667 ‘Jenkins’, bears no hint of the Amati connection. It may be that this was due to Stradivari deciding he could stand on his own two feet, or perhaps Amati intervened and forbade him from making such statements on his labels. We will never know how many copies of the ‘Alumnus’ label Stradivari ordered from the printers, but they were wasted money. To complicate matters, Cozio cites an as-yet undiscovered ‘Alumnus’ label of 1665 and states that some of his Stradivari instruments from that period have Amati’s label in them. There is another recorded label (reported to Arnaldo Baruzzi by Georges Chanot-Chardon and cited in his book La Casa Nuziale), but presently unknown, that states ‘made at the age of 13’. In the 19th century John Betts mentioned a Stradivari label dated 1660 in his workshop notes. And so it goes on.

We will never know how many copies of the ‘Alumnus’ label Stradivari ordered from the printers, but they were wasted money.

We have no current supporting evidence for any of these assertions. Whatever Stradivari was doing and wherever he was doing it before 1667 remains a mystery. In that year he made an ambitious, perhaps opportunistic, or possibly compelled marriage to Francesca Feraboschi. She was a widow and four years older than Stradivari, who at that time was 22 or 23. He moved to her parish of Sant. Agata, where the couple lived in the house of Francesco Pescaroli, and a baby arrived only three months after the wedding. It is difficult to think what sort of prospects the young Stradivari could offer to the widow Feraboschi. But the years spent in the ‘Casa Nuziale’, as Baruzzi’s book has it, are the years in which Stradivari set about establishing himself as a serious independent violin maker in Cremona.

The ‘Sunrise’ Stradivari shows Stradivari’s early mastery of complex inlay and perhaps gives a clue to his background. Photos: Jan Röhrmann, Antonius Stradiuarius Vol I–IV

To loosen this tangle, we can look at Stradivari’s early work and do our best to interpret it. The instruments he made in his early years are quite distinctive and varied. Putting them in developmental order is not easy, however. As the Hills pointed out, as far as they could tell in 1902 when their Stradivari book was published, only three early examples had authentic, unaltered labels. Some things are immediately obvious though. The resemblance to Amati’s work is strictly superficial. And the wood is desperately poor stuff, suggesting that Stradivari was struggling to make his mark.

If we take 1680 as a convenient marker for the end of his developmental years, the year that he moved house to the Piazza Domenico, we have about 20 known instruments to examine; a fairly meagre output over 14 years. We can only speculate what he was doing the rest of the time – assisting other luthiers, making instruments that have not survived or are yet to be recognised, or perhaps engaged in a totally different craft. But the common notion that he was distracted by the making of guitars, harps and mandolins does not hold true for this first period. The 1681 harp, 1688 guitar, 1680 mandolin and most of the other non-violin family instruments emanate from his second workshop in San Domenico. Only the 1679 ‘Sabionari’ guitar may have come from the Casa Nuziale as far as we know.

It is tempting to speculate that Stradivari was an apprentice in the Amati workshop when the decorated ‘Youssoupov’ was made in 1656

A significant point for me is that by 1680 Stradivari had already perfected his wonderful and innovative decorated instruments – attested by the 1677 ‘Sunrise’ and the 1679 ‘Hellier’. These possibly give us a clue to his background. They are almost unprecedented in the complexity and completeness of the inlay and design as far as the earlier Cremonese masters go. Aside from the surface painting of the famous Andrea Amati sets, there are only two Nicolò Amati instruments that definitely anticipate Stradivari’s inlay work – the 1656 ‘Youssoupoff’ and c. 1650 ‘Prague’ displayed in the Czech Museum of Music. These show the doubled purfling, bounding ‘dot and diamond’ mother-of pearl, and paste inlay patterns on the scroll, rib corners and back button. Stradivari must have seen these instruments and it is tempting to say that he might have been old enough to have served as an apprentice while they were being made. His characteristic and lifelong perfection in purfling might even have stemmed from this experience. Alternatively it is possible that he was at this point apprenticed in an ‘intarsio’ workshop (specialising in fine marquetry) and in this indirect way engaged with Nicolò Amati.

Another theory about Stradivari’s early trade is offered by Charles Beare, who suggests that the detailed carving covering the 1681 Stradivari harp indicates that he may have apprenticed as a woodcarver rather than a violin maker. There were plenty of opportunities among his contacts. His landlord at the Casa Nuziale, Francesco Pescaroli, was a sculptor and architect and also a neighbor of Nicolò Amati. His wife’s first husband, Giovanni Capra, left a fully equipped woodworking shop as part of his estate. Yet the harp remains the only example of figurative carving in all of Stradivari’s production as far as I’m aware. He departed from carving conventional scrolls only on the rare occasions he made the simplified ‘shield’ type, exemplified by the small-sized ‘Gillot’ violin, and the original d’amore head of the ‘Kux’ viola, both from 1720. It is just as plausible that Stradivari’s sketches for the carved pillar of the harp, still extant in the Museo di Violino in Cremona, were merely guides for a neighboring specialist carver to work from. He wouldn’t have had to look far.

By 1680 Stradivari had already perfected his wonderful and innovative decorated instruments… These possibly give us a clue to his background.

Does the 1681 Stradivari harp suggest that Antonio originally trained as a wood carver? Photo: Getty Images

These enticing details are all we can really see of Stradivari’s early life. We know that his connections with the Amati, Feraboschi, Capra and Pescaroli families provided a background of skilled professional handwork into which he was drawn. How he found his way into this milieu is what we don’t yet know; without the records of his birth or his own family, it is just the work of the imagination. And there is plenty for the imagination to work on.

Francesca Feraboschi had married Giovanni Capra in 1662. He was the son of the successful sculptor and architect Alessandro, and himself had a woodworking shop as we have seen. In 1664 Giovanni was shot dead by Francesca’s brother, while she was pregnant with their first child. As part of the settlement with the Capra family, she had to give up the baby daughter she carried. Undoubtedly estranged from them, she moved back to her parents’ home in Sant. Agata. Three years later she was pregnant again, by Antonio Stradivari, and then married for a second time. She bore Stradivari five more children, including his violin making sons Francesco and Omobono, and died in 1698 aged about 58. Stradivari gave her a lavish funeral, but married again within the year and, as Carlo Chiesa points out in the 2013 Ashmolean exhibition catalog, still found time to haggle over the funeral expenses. It would take a Shakespeare to unravel this plot, and the passions and personalities involved.

In part 2 John Dilworth looks more closely at what we can learn from Stradivari’s earliest instruments.

John Dilworth is a maker, writer and expert. He has written extensively about fine instruments and their makers, and is a co-author of ‘The British Violin’, ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ and ‘The Voller Brothers’ among other books.

References

Hill, W.H. & A.F., Antonio Stradivarius, His Life and Work, W.E. Hill & Sons, London, 1902.

Baruzzi, A., La Casa Nuziale, The Home of Antonio Stradivari 1667–1680, W.E. Hill & Sons, London, 1962.

Charles Beare, Carlo Chiesa, Peter Beare and Jon Whiteley, Stradivarius catalogue, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 2013.

Antonius Stradiuarius Vol I–IV, Jost Thöne Verlag, 2010.