Antonio Stradivari was driven by an urge to experiment and constantly changed his models, even into the last years of his life. Around 1730, when he was well over 80, one of these changes took place in the workshop and a smaller cello model, the ‘forma B piccola’, began to appear.

The c. 1730 ‘Pawle, Ben Venuto’ is one of the surviving examples of these cellos, as are the 1730 ‘Feuermann, De Munck, Gardiner’ and the 1731 ‘Braga’. With a body length of between 74.2 and 74.6 cm, these instruments are much shorter than early models such as the 1690 ‘Medici, Tuscan’ (79.25 cm), the 1696 ‘Lord Aylesford’ (79.4 cm) or the 1701 ‘Servais, Chimay’ (78.5 cm). They are also distinctively different from Stradivari’s ‘forma B’ model, which produced cellos with a length between 75.6 and 75.9 cm, including the 1710 ‘Baron Rothschild, Gore-Booth’, the 1714 ‘Batta’ and the 1720 ‘Piatti’.

It seems unlikely that the octogenarian was alone responsible for such a change, although the daily activity of the Stradivari workshop still appears to have been heavily conditioned by his authoritarian figure and strong personality. Indeed many experts believe that Antonio’s sons were involved in the development of the ‘B piccola’ cello form. The Hills wrote: ‘The […] few years preceding 1730 are, as far as we know, blanks in violoncello construction, but in that year we come to a distinct type of Stradivari instrument. Form and dimensions have undergone a change, and the character of the work is no longer that which we have followed during the preceding twenty years. The master’s advanced age may account for both changes. He doubtless realised, however reluctantly, that at four-score years and more his physical strength no longer permitted him to undertake the task of violoncello construction; consequently, while still assiduously applying himself to the making of violins, he in great measure resigned the violoncello work to his two sons, who were possibly assisted by Carlo Bergonzi.’ [1]

It seems unlikely that the octogenarian was alone responsible for such a change, although the daily activity of the Stradivari workshop still appears to have been heavily conditioned by his authoritarian figure and strong personality.

Simone Ferdinando Sacconi agreed, and cited the paper model of the f-holes for the ‘forma B piccola’, which appears to bear the handwriting of one of the sons: ‘On the back of the sheet of paper the same design has been repeated with modifications of the measurements and of the placing of the ff holes (the diameter of the lower eyes has been reduced from 19 mm. to 16.5 mm. and they have been placed further apart by a distance of 15 mm.) and in the hand-writing of the sons of Stradivari is written: Per far li occhi della forma B piccolo del violoncello (To make the eyes of the small B form of the violoncello).’ [2] Several experts have since agreed that the handwriting on this document is most likely to be that of Francesco Stradivari. [3],[4]

Sacconi believed that the reduction in size for the ‘forma B piccola’ resulted in a relative loss of sonority: ‘The modification made by the sons is illuminating with the reference to the indication already given, concerning the influence of the width of the central vibrating surface of the table circumscribed by the ff holes, on the sonorous power of the instrument. In fact, by shortening the mould they have reduced the length of the instrument and consequently have diminished the internal air volume of the body. To restore the now altered equilibrium it would have been necessary to place the ff holes nearer each other rather than further apart as the sons did mistakenly, showing by this that they had neither understood nor assimilated the fundamental principles on which their father conceived and carried out his own instruments.’ [5]

Bruce Carlson, however, saw the advantages of the smaller model, writing: ‘The ‘forma B piccola’ with its reduced breadth is the more comfortable to play upon as the shoulder of the upper bout does not interfere at all with the cellist when playing in the higher position on the fingerboard. This type of cello has […] been very successful and popular.’ [6]

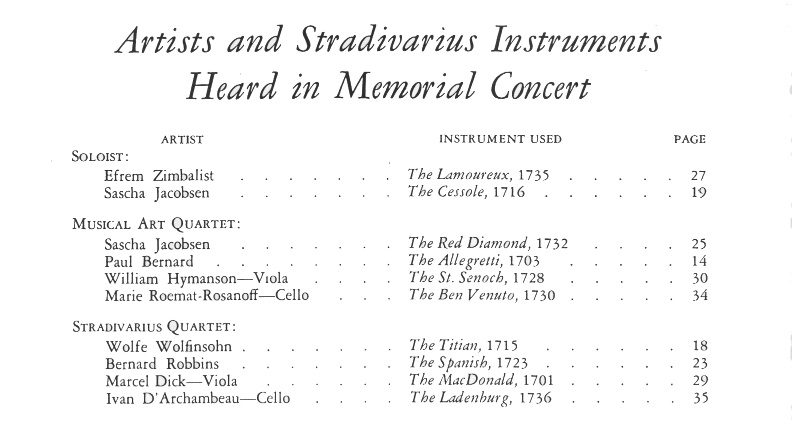

Section from the program for the 1937 Stradivari Memorial Concert, in which the cello is listed as the ‘Ben Venuto’

The original drawings and patterns for the ‘Pawle’ have survived, as has the lower block. This material can be seen at the Museo del Violino in Cremona and is reproduced in the catalog of the former Museo Stradivariano. [7]

The ‘Pawle’ is named after the English collector Frederick Pawle of Northhoole, Reigate and is also known as the ‘Ben Venuto’ [8] or ‘Benvenuto’ [9] – we shall see shortly how the cello acquired this second name.

The back of the instrument is of two pieces of attractive maple with small flames running almost horizontally. The ribs exhibit a similar pattern while the head is much plainer and is unusually cut on the slab. The table is formed from two pieces of medium-grain spruce, which grows coarser towards the edges. The fine varnish is still abundant and of the brilliant red-brown color characteristic of Stradivari’s instruments built around 1730. Overall the cello is in an exceptional state of preservation.

The craftsmanship is of typically high quality and the scroll is particularly well designed and executed. The f-holes are perfectly cut while the purfling, although stopping somewhat short in the corners, is clean and refined. These details surely point to a younger hand at work. Possible contenders are of course Francesco and Omobono, but Francesco was already in his 60s and Omobono, although ten years younger, does not appear to have inherited his father’s steady hand. Carlo Bergonzi also assisted in the workshop, although his style is more often seen in later Stradivari cellos. It’s also possible that this project began earlier than 1730. If so, Antonio’s third son, Giovanni Battista Martino [10], could have played a part in it. Giovanni Battista does not seem to have taken up an ecclesiastical career, and may have indeed helped his father in the workshop. Unfortunately he died in 1727, aged only 24. (For a full discussion of the involvement of Stradivari’s sons in the workshop, see John Dilworth’s Carteggio feature.)

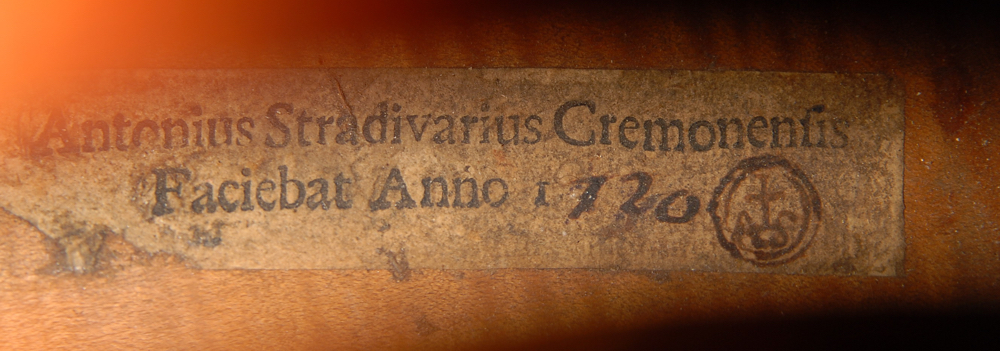

The date on the label of the ‘Pawle’ appears to have been altered from 1730 to 1720

The cello’s label is original but its date appears to have been changed by a later hand. The Hills reported that the label was originally dated 1730 and was ‘altered by the late Mr. Laurie, to 1720’. [11] They were best placed to have known this, because, as we shall see, the cello returned to their London shop several times over the years. And indeed a close examination of the label does suggest that the digit ‘3’ has been altered into a ‘2’.

It is believed that the ‘Pawle’ was brought to Paris by the Italian collector and dealer Luigi Tarisio, who sold it to the French luthier Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume in the first half of the 19th century. Although highly probable, this theory is not supported so far by written evidence. We do know that the instrument was auctioned at Phillips in London in 1866 as part of the estate of the Honorable Mr Greaves, but apparently it did not reach the expected price and was bought in.

Shortly afterwards, the involvement of the Hill family with the cello began. William Ebsworth Hill acquired the instrument and sold it in 1867 to Frederick Pawle for £230. Ten years later, in 1877, the Hills bought the cello back from Pawle for £380 and the following year sold it to Edward Hennell for £500. Two years later the instrument was back at the Hills, who bought it for £475 and resold it a few months later to the collector Caspar Gottlieb Meier (1837–1915) for £525.

In 1882 the cello left England for France, where it was sold by Meier to the Parisian luthiers Gand & Bernardel, but in 1885 the instrument returned to England with its new owner David Johnson, who had acquired it for £600. In the same year the Hills once again purchased the cello, this time for £650, and sold it immediately afterwards to Baron Johann Ludwig Knoop (1846–1918), a wealthy collector of fine instruments (see our feature on Knoop). A few years later Knoop commissioned the dealer David Laurie (1833–1897) to sell the cello and the deal was made in 1890, when Alexander Murray became the new proprietor of the ‘Pawle’. Five years later Murray passed the cello to his friend, the German cellist, teacher and composer Hugo Becker (1863–1941).

Around 1934, in view of the dramatic political changes that were taking place in Germany, the instrument was taken to America.

Around 1908 Walter H. Merton of Frankfurt, son of the German entrepreneur and philanthropist Wilhelm R. Merton, one of the founders of the University of Frankfurt, bought the instrument from Becker. The new owner presented the cello to his bride, Christine Henriette van Toulon van der Koog (1887–1944), a Dutch cellist and student of Becker. Around 1934, in view of the dramatic political changes that were taking place in Germany, the instrument was sold to the New York dealer Emil Herrmann, who took it back with him to the US. Two members of the Merton family who had emigrated to the US were struggling financially at the time and the proceeds from the sale were therefore ‘most welcome’. This expression was italianized by Herrmann and the cello thus received its curious name ‘Ben Venuto’.

Christine Merton, who was given the ‘Pawle’ as a bride in the early 20th century. Photo courtesy Juan von Haselberg

Herrmann sold the instrument in 1937 to Caroline Fesler (c. 1878–1960) of Indianapolis for $42,000. At first Fesler, who was fond of classical music and became patron of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra and founder and vice president of the Ensemble Music Society, lent the instrument to the cellist Marie Roemat-Rosanoff (1896–1967) of the New York Musical Art Quartet, and it was Roemat-Rosanoff who played it at the Stradivari Memorial Concert at Carnegie Hall that same year. Later on Fesler agreed to part with the ‘Pawle’ and sold it to the cellist, who played it for the rest of her life. In 1975 the cellist Paul Olefsky (1926–2013), an emeritus professor at the University of Texas at Austin, purchased the cello from the heirs of Roemat-Rosanoff, and he then auctioned it ten years later at Sotheby’s in London in November 1985. The instrument was not sold but shortly after it became part of the notable collection of the American Bernard Goldblatt.

In 1990 the cello became part of the Chi Mei Cultural Foundation of Taiwan via the dealers Bein & Fushi. It is now exhibited in the Chimei Museum and has been occasionally lent to musicians for concerts.

The ‘Pawle’ has taken part in several exhibitions, including the South Kensington Loan Exhibition of 1872, when it was described in the catalog as a ‘magnificent specimen’. [12] In 2008 it was in Montpellier, France, [13] and afterwards in Cremona for the 1730–1750 nell’Olimpo della Liuteria. [14] The cello is featured in the brochure for the Stradivari Memorial Concert [15] as well as books by Ernest N. Doring, [16] Herbert K. Goodkind, [17] and the catalog of the Chi Mei Foundation. [18]

Thanks to Juan von Haselberg, Roberto Regazzi and Alessandro Bardelli for assistance with source materials. Photographs of the cello courtesy of the ChiMei Museum.

Alessandra Barabaschi is an Italian art historian and has authored several books including the four-volume ‘Antonius Stradivarius’.

Notes

[1] Hill, W.H.; Hill, A.F.; Hill, A.E., Antonio Stradivari. His Life and Work (1644–1737), W.E. Hill & Sons, London, 1902, reprint 1963, Dover, New York, p. 142.

[2] Sacconi, Simone F., I ‘Segreti’ di Stradivari, Libreria del Convegno, Cremona, 1972, English edition, reprint 2000, p. 31. NB The original document spells ‘piccola’ with one ‘c’, which appears to have been a Stradivari error.

[3] Biddulph, Peter; Chaudière, Frédéric, catalogue Antonio Stradivari, Musée Fabre/Actes Sud, Montpelier, July 2008, p. 84.

[4] Reuning, Christopher, Cremona 1730–1750 nell’Olimpo della Liuteria, Consorzio Liutai A. Stradivari, Cremona, 2008, p. 76.

[5] Sacconi, S.F., op. cit., p. 31.

[6] Manfredini, Cinzia; Carlson, Bruce, I violoncelli di Antonio Stradivari, Consorzio Liutai Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, 2004, p. 87.

[7] Mosconi, Andrea; Torresani, Carlo, Il Museo Stradivariano di Cremona, Cremonabooks, Cremona, 2001, p. 90.

[8] Brochure of the Stradivarius Memorial Concert, The Stradivarius Memorial Association, New York, 20 December 1937, p. 34.

[9] Herrmann, Emil, Certificate, New York, June 10, 1937; Bein & Fushi, Certificate, Chicago 1991.

[10] Chiesa, Carlo; Rosengard, Duane, The Stradivari Legacy, P. Biddulph, London, 1998

[11] Hills, op. cit., p. 144.

[12] Engel, Carl, A Descriptive Catalogue Of The Musical Instruments In The South Kensington Museum, London, 1874, reprint 2009, p. 364.

[13] Biddulph, P.; Chaudière, F., catalogue Antonio Stradivari, op. cit.

[14] Reuning, C., Cremona 1730–1750, op. cit.

[15] Brochure of the Stradivarius Memorial Concert, op. cit.

[16] Doring, Ernest N., How Many Strads?, Bein & Fushi, Chicago, 1945, reprint 1999, p. 299.

[17] Goodkind, Herbert K., Violin Iconography of Antonio Stradivari, Larchmont, New York, 1972, p. 631.

[18] Chen, Jen-wu, The Chi-Mei Collection of Fine Violins, Chi-Mei Culture Foundation, Taiwan, 1997, p. 46.