It has been said that a great violinist could get a good sound out of a cigar box – but Fritz Kreisler actually started out on one, although I doubt whether any sound came out of it. According to his biographer Louis Lochner, the young Kreisler listened to his physician father’s amateur quartet as a child and reacted even then to sour notes. ‘Soon I made myself a would-be violin out of a cigar box over which I stretched shoestrings; and I’d pretend I was playing right…’ [1] He progressed to a toy fiddle, on which he played so well that a proper small violin and bow were quickly substituted, and his father started giving him lessons.

Kreisler in recital at the Royal Albert Hall, London, in 1932. Photo: Tully Potter Collection

Aged eight he was presented with a half-sized Thir violin at the Vienna Conservatory, and at ten he received a three-quarter-sized Amati for winning the Austrian State Prize. In 1887 he won first prize at the Paris Conservatoire and was lent the 1708 ‘Davidov’ Strad – now in the Paris Musée de la Musique – for the prize ceremony; he was also presented with a Gand-Bernadel instrument as part of his award.

Returning to Vienna, Kreisler received a fine Giovanni Grancino from his father, which became his favorite for the next eight years. Then one day he called on an old architect friend, who said: ‘Here is an old, battered violin that you can have.’ After he got it home he realised it was a Nicolò Gagliano, ‘of entrancing tone and quality’, as he said in 1908. ‘It became the best beloved of my violins until within three years ago.’ [2] When he made his Vienna debut with the Philharmonic under Hans Richter in 1898, he was lent the 1732 ‘Baillot’ Strad for his performance of the Bruch G minor Concerto.

One day [Kreisler] called on an old architect friend, who said: ‘Here is an old, battered violin that you can have’

At the turn of the century Kreisler bought the 1735 ‘Mary Portman’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ for $10,000 from the dealer George Hart. But in 1904 he heard the ‘Hart’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ (now known as the ‘Hart, Kreisler’ c. 1741), which Hart had sold to the collector John Adam. Kreisler begged Adam to let him buy it and, having heard him try it, Adam consented, asking just the $10,000 he had originally paid. It became Kreisler’s favored violin, of which he famously said in 1908, ‘I shall never hear a voice more beautiful than my “Hart” Guarnerius.’ [3] This was presumably the instrument that he used to make his first five recordings, in Berlin in 1904. He certainly premiered the Elgar Concerto on it in 1910 and probably used it for his next recordings in New York and London between 1910 and 1916, before selling it in 1917.

In the meantime in 1908 Kreisler had acquired the 1726 ‘Greville’ Stradivari from Ernest Kempton Adams of New York. Adams prepared a 20-page brochure, dedicated to Kreisler, about the fiddle, but after a year the violinist sold it to Lyon & Healy of Chicago. He also purchased the 1732 Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ that had been played by the Hungarian Tivadar Nachéz (he kept this until 1921) and in 1914 he bought a 1733 Stradivari from Alfred Hill, now known as the ‘Huberman, Kreisler’. This Strad became his favorite and can be heard on Kreisler’s 1926–27 Berlin concerto discs with Leo Blech – Brahms, Beethoven and Mendelssohn – and the 1928 sonatas with Rachmaninov. According to a letter from the Hills dated 1949, the violin did not have a Stradivari head when Kreisler acquired it, but Hill was able to fit one a few years later. Hills bought it back from him in 1936 and sold it to Bronisław Huberman the next year.

The c. 1730 ‘Kreisler’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ was Kreisler’s preferred instrument for many years. Photos: Peter Biddulph Ltd

More photosIn 1926 Kreisler acquired the c. 1730 Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ which is named after him and is today the violin most associated with him. Owned by Jean-Andoche Junot, one of Napoleon’s generals who was given the title Duke of Abrantès, it was seized when Junot’s ship was captured by British privateers in the Napoleonic wars and ended up in Whitehaven, where the vicar bought it for £2 from the sailors. He sold it to the collector William Thomson, who branded his initials into the scroll, and it passed through several more owners, including ‘two ladies named Day’, before finding its true haven with the immortal Fritz. It was highly praised by Alfred Hill, who wrote in a letter dated November 1926: ‘My father declared the violin to be the finest Guarneri he had ever seen. I recognize it to be one of the few of the first rank.’

By the 1930s this Guarneri had supplanted the 1733 Strad in Kreisler’s affections. It was this fiddle that his wife, Harriet, brought to the hospital in 1941, a month after he had been knocked down by a truck in a New York street. Worried that his ability to recall music might have been affected, Harriet asked him to play part of the Andante of the Mendelssohn Concerto – which he did, flawlessly. I suspect the 1935 re-recording of the Mendelssohn Concerto with Sir Landon Ronald, the 1936 re-recordings of the Brahms and Beethoven concertos with Barbirolli and the 1939 re-make of Mozart’s K218 with Sir Malcolm Sargent were played on this Guarneri. Sir Malcolm recalled that at the 1939 sessions, ‘an orchestral player asked me if I could persuade Kreisler to try his violin. Kreisler graciously consented, and was soon overwhelmed by similar requests. Violin after violin was played. The magnificent tone produced by each was a revelation to the owner!’ [4] Kreisler bequeathed the Guarneri to the Washington Library of Congress and handed it over in 1952, when he was no longer giving concerts.

Kreisler liked to pass the Parker off as a Balestrieri or even a Strad – by the 1940s he was apparently referring to it as the ‘Parker’ Stradivari

Kreisler, who spent much of his life pretending that some of his compositions were by Pugnani, Vivaldi and so on, often tricked listeners by playing a violin that was not by a celebrated Italian maker. One such was an 1850 J.B. Vuillaume copy of Paganini’s Guarneri ‘Cannon’ violin, which Kreisler bought in 1925 and parted with only in 1960. One of Rudolph Wurlitzer’s customers who had a Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ on approval, returned it after hearing Kreisler play what he thought was a ‘del Gesù’ – it was actually the Vuillaume – and asked Wurlitzer to find him a better one. [5]

Kreisler passed off his c. 1715 Daniel Parker violin as a Balestrieri and even called it the ‘Parker’ Stradivari. Photos: Tarisio

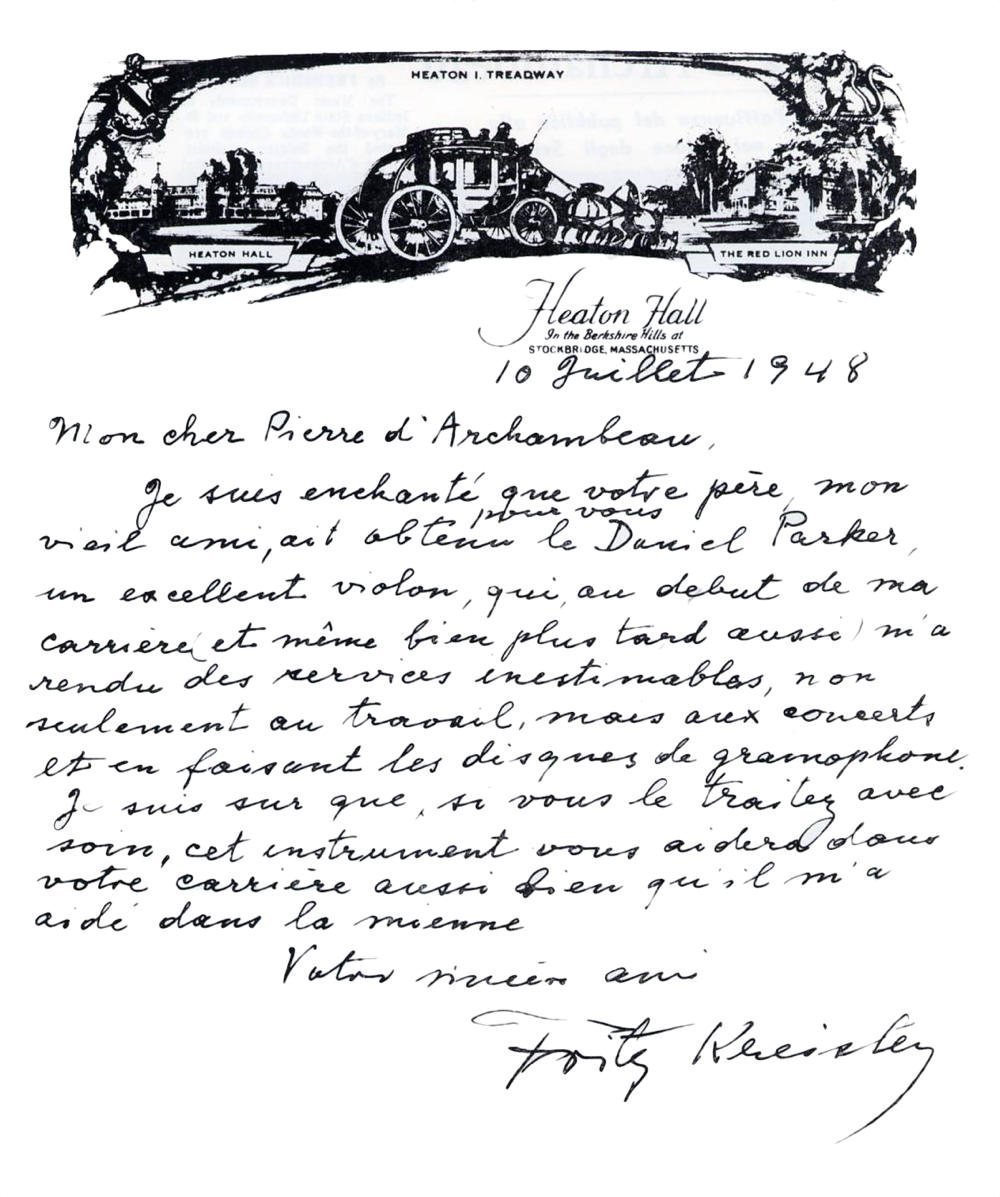

More photosEqually confusing was the 1715 instrument by the English maker Daniel Parker, which Kreisler bought for £50 from Alfred Hill early in 1911. When he used it for one of the works that he played at Queen’s Hall with Sir Henry Wood on December 21, 1910 – the Elgar and Brahms concertos and Wieniawski’s Airs Russes – apparently no one could tell the difference between the Parker and the ‘Hart’ Guarneri. According to Alfred Hill, Kreisler liked to pass the violin off as a Balestrieri or even a Strad – by the 1940s he was apparently referring to it as the ‘Parker’ Stradivari. He sold the Parker to Wurlitzer in 1948.

The Hills were always offering Kreisler treasures and it was from them that in 1928 he bought the 1711 ‘Earl of Plymouth’ golden period Stradivari. At this stage he had two Stradivari violins, even though he felt that most auditoria of the era were too big for a Strad’s carrying power. ‘The Strad is excellent for a small concert hall,’ he said. ‘The Guarnerius has much more power.’ [6] He kept the ‘Earl of Plymouth’ until 1945, when he sold it to Wurlitzer in New York.

Kreisler’s letter to Pierre d’Archambeau, whose father had bought the Parker

The year 1936 brought a positive convulsion in his armoury of fine violins: out went the 1733 Stradivari and in came the 1734 ‘Lord Amherst of Hackney’ and a 1707 Pietro Guarneri of Mantua, both from Hills. In 1939 Kreisler bought a fine 1735 violin by Carlo Bergonzi I of Cremona. It is doubtful whether he played it much, and it fell victim to his post-war cull, when Harriet rightly pointed out that it was wrong to have six violins in the house when some could be used by other players. The instrument went to Wurlitzer and was sold in 1949 to Angel Reyes. For several years in the 1980s it was owned by Itzhak Perlman.

Kreisler’s bows were fit to be employed with his great violins. He had a lovely example by Tourte, given to him by Frank H. Tubbs, editor of Music Life, half a dozen by Hill which he used a great deal, a Pfretzschner he liked and a Franz Albert Nürnberger Jnr. He preferred to have the bow hair very taut and anecdotal evidence suggests that he often did not loosen it between gigs.

There are many stories about Kreisler arriving for a concert and admitting that he had not touched his violin for days – he was not keen on practising or rehearsing. On one occasion, the pianist Michael Raucheisen visited him at his New York hotel on the day he arrived by liner from England, with a Carnegie Hall performance scheduled that evening. Raucheisen reported: ‘The violin had remained in there ever since his Albert Hall concert in London, and the case had not even been opened. With utmost composure [Kreisler] examined the instrument and noticed that the A and D strings had snapped during the ocean voyage. Any other violinist would have suffered tortures.’ [7]

‘With utmost composure Kreisler examined the instrument and noticed that the A and D strings had snapped during the ocean voyage. Any other violinist would have suffered tortures’

On strings, Kreisler told an unnamed critic: ‘I find good ones wherever I happen to be. I am not a faddist.’ [8] However, the violinist Stephen Redrobe has more precise information which accords with what we hear on the records. [9] Up to about 1912 Kreisler used a gut D, A and E, but after this he switched to a covered gut D, and in the 1916–18 period he changed to a steel E, influencing Jacques Thibaud to do the same. (He knew the perils of gut E strings – at his US debut in Boston on November 9, 1888, he twice broke one in the Mendelssohn Concerto: in the Andante he continued on his A string and in the finale he exchanged instruments with concertmaster Franz Kneisel.) He retained the gut A, but in the mid-1920s, at the time he was making his first electrical recordings, he went over to a covered gut A; so that by the late 1920s he was using the covered gut G, D and A. In later years he patronized and endorsed Armour & Co. of Chicago, with whom he was friendly – a meat packing firm, they supplied gut to European string makers for years until in 1912 they started manufacturing their own strings.

Kreisler had a vivid imagination and enjoyed telling liberally embellished stories about his fiddles. In 1940 he spun one particular tall tale to the Christian Science Monitor about a Guarneri in his collection. According to Kreisler, it was brought to Britain from Spain by a sailor who had stolen it in a raid during the Napoleonic wars and it had ended up in the possession of a London pub landlord called Twombley. Kreisler discovered it there and repeatedly tried to buy it, but despite his best endeavours he was not able to acquire it until Twombley died, when he bought it from the old man’s daughters. [10] From the link with the Napoleonic wars, this story must refer to the c. 1730 ‘Kreisler’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, but most of it is pure invention.

Tully Potter is a journalist and music critic. He is a regular contributor to various international music journals, including The Strad, and has written a biography of Adolf Busch, published in 2010.

Notes

[1] Kreisler, by Louis P. Lochner, Macmillan, New York, 1950; expanded edition Paganiniana Publications, Neptune City, N.J., 1981, p. 2.

[2] Reprinted in The Cremona, May 1908, from Musical Courier; quoted in Ibid., p. 349.

[3] B. Henderson, ‘Kreisler’s Violins’, The Strad, October 1908.

[4] Letter to The Times, April 26, 1958.

[5] Anecdote from Charles Beare in Michael Darnton, ‘Alternating Voices’, The Strad, January 1987.

[6] Lochner, op. cit., p. 351.

[7] Quoted in Ibid., p. 354.

[8] Ibid., p. 357.

[9] Conversation with the author, January 22, 2017.

[10] Quoted in Lochner, op. cit., p. 347.