What is the connection between Antonio Stradivari, Luigi Tarisio, J.M.W. Turner and fountain pen nibs? The answer is Joseph Gillott, entrepreneur, industrialist, collector and patron of the arts – an extraordinary man who was born in Sheffield in 1799. By the year of his death in 1872 he had accumulated one of the most important and diverse collections of Cremonese master instruments in history.

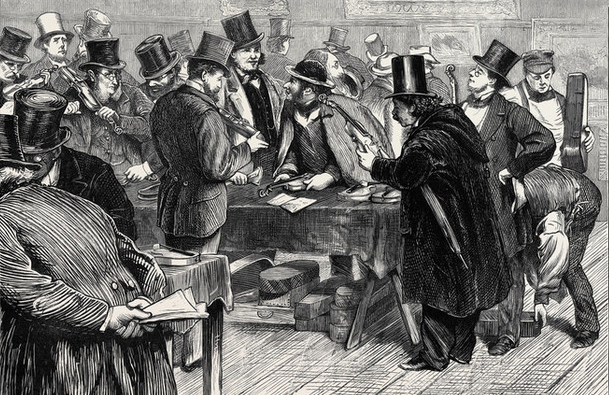

After Gillott’s death, his instrument collection made up 153 lots at the celebrated Gillott Sale at Christie, Manson & Woods on April 29, 1872, part of a six-day auction which included his extensive art collection. The instrument sale alone caused a sensation, and was the subject of a contemporary engraving, Men Inspecting the Violins. It included the 1715 ‘Emperor’ Stradivari, the 1672 ‘Mahler’ and 1734 ‘Gibson’ violas, the 1697 ‘Primrose’ Andrea Guarneri viola and at least one fine Guarneri ‘del Gesù’: the 1732 ‘Gillott, Dunmore’.

‘Men Inspecting the Violins’: engraving from the sale of the Joseph Gillott Collection, April 1872

Gillott himself is a fascinating figure, but also a representative one in the history of violin ownership. He was one of the first examples of a pure collector, who was neither a musician nor an aristocrat with inherited wealth, but a member of a new group in society made possible by the Industrial Revolution. This group, the nouveaux riches, was able to accumulate wealth through the individual’s own initiative, and in so doing broaden the market for pedigree instruments. These new private collectors were a phenomenon of the Victorian era in England, when they began to flaunt their possessions in competition with the traditional landed gentry. For many, it seems to have mattered not what they collected; instead it was the search for prestige and acceptance that drove them.

Gillott himself bought precious stones and silver as well as instruments, and he showed no signs of a musical nature or any particular connoisseurship. If he did have a passion, it was for paintings and he was an important patron of Joseph Mallord William Turner. He clearly saw the value of Turner’s work, and formed a friendship with the painter, who was otherwise known for his solitary nature.

The ‘Primrose’ Andrea Guarneri viola of 1697 was one of the jewels of Gillott’s collection. Sold by Tarisio in 2012

More photosGillott’s wealth came from penny pen nibs. He was the son of a cutler in Sheffield and, after the briefest of educations, walked to Birmingham in 1821, supporting himself as a knife grinder. A relative of the family, one John Mitchell, was already established in Birmingham, making steel pen nibs on a small hand-press. This was a recent innovation; steel pens were a novel alternative to traditional quills, and generally felt to be a little too stiff to reproduce the quality of quill calligraphy. Gillott was drawn into the trade and rented a workshop in the steel foundry of G. & P.H. Muntz. [1]

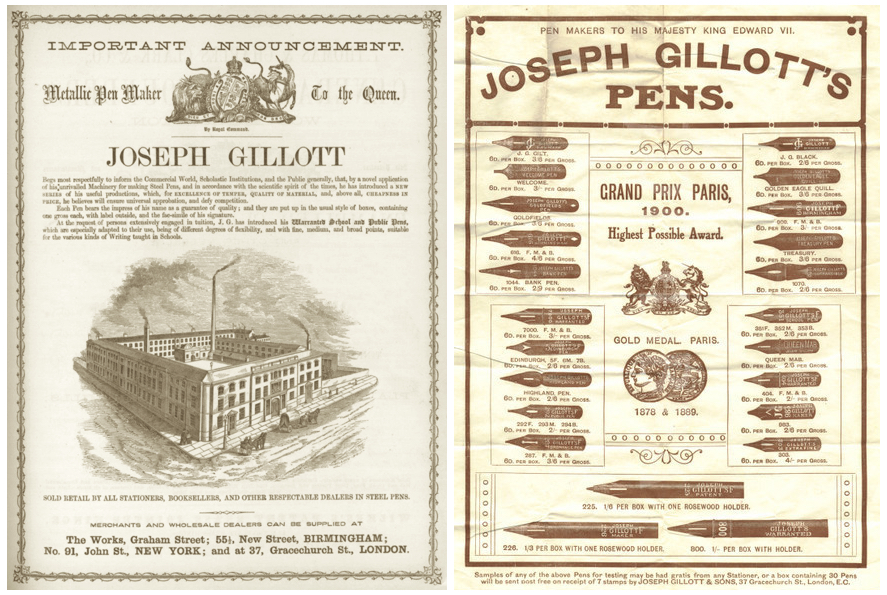

Gillott was clearly an ambitious and ingenious man. He soon developed a small machine that could produce pen nibs quickly and efficiently, and with an important innovation in the form of small incisions which made them as flexible and sensitive as quills. Patented in 1831, they were an immediate success. By 1839 Gillott’s company had produced over 44.6 million nibs and had offices in Paris and New York. It is astonishing that these simple and unassuming objects could generate so much wealth. In an age of increasing literacy, however, pens were of huge importance, and the skilled process of cutting goosefeather quills, which had very limited life, was a great obstacle to progress. Gillott’s pen nibs were in this period as revolutionary as photocopiers and office printers, and like today’s tech giants, he grew fabulously rich.

Gillott’s pen nibs were in this period as revolutionary as photocopiers and office printers, and like today’s tech giants, he grew fabulously rich

In 1840 Gillott was appointed Pen Maker to the Queen. In 1851 he purchased a house in Edgbaston, just outside Birmingham, which included three picture galleries. In 1861 he acquired The Grove, his southern residence in Stanmore, Middlesex. Despite his new fortune, Gillott evidently enjoyed the company at the Hen and Chickens, a Birmingham hotel where he spent much of his social life among local businessmen, and was considered a private and undemonstrative man.

Advertisements for Joseph Gillott’s pens, showing his Birmingham factory, Victoria Works (left)

Gillott started collecting paintings quite early on. Turner’s biographers state that Gillott paid him a visit in the mid-1830s at his home at 47 Queen Anne Street, Marylebone, asking to buy his paintings. When Turner replied in typically surly tones that he hadn’t any to sell, Gillott offered to exchange them for his own ‘Birmingham pictures’. By this he meant printed banknotes, £5,000 worth of which he rolled out on the table between them. ‘Mere paper,’ said Turner; ‘for mere canvas,’ replied Gillott. [2] This was an astonishing amount for the time, the equivalent of about £500,000 today.

Nevertheless, Gillott was reportedly able to sell this initial acquisition shortly afterwards at a profit of some 300%. Among the celebrated Turner works that remained in Gillott’s collection were the Landscape of Walton Bridge (which recently sold for over £3 million), and his View of Zurich now in the Tate Gallery, London. He had many agents to assist him acquire his paintings; ironically, given his profession, he is said to have been practically illiterate and his handwriting illegible, and he seems to have preferred to trade in goods rather than cash. Nevertheless, he was widely referred to as ‘the Governor’. He was generous towards his associates and particularly to his painter friends, including Turner and William Etty, and his collection grew to include works by Gainsborough, Constable and Landseer as well as Rubens and Ruysdael.

‘View of Zurich’ by Joseph Mallord William Turner, 1841–2, now part of the Tate Gallery collection in London. Photo: © Tate

But a new pursuit was introduced to Gillott in 1848 by one Edwin Atherstone. Born in Nottingham, Atherstone was a music teacher and poet, and owner of a Matteo Goffriller violin. He seems to have persuaded Gillott of the value of old instruments, and the following year Gillott exchanged 60 of his paintings through John Hart, then the leading dealer in England, for the first items of his new collection. [3] This would almost certainly have included the small-sized 1720 Stradivari with its distinctive shield-shaped head, still known as the ‘Gillott’. This is a true collector’s piece, of lesser musical value but great novelty. Ideal for the well-heeled dilettante, it was brought to Hart by Luigi Tarisio.

The ‘Gillott’ Stradivari small violin, with its distinctive shield-shaped head. Photos: Sotheby’s

More photosTarisio made his first visit to London in 1848. The timing was fortuitous. It is unclear if they ever met, but Tarisio was, like Gillott, a man of little or no education, who famously walked from Milan to Paris in 1827 to sell his violins – a little further than Gillott’s journey from Sheffield to Birmingham, granted. Tarisio’s first contact in London in 1848 was John Hart and it was through Hart that his Cremonese rarities were spread through the country.

Another source for Gillott was Charles Reade. A novelist and violin connoisseur, Reade was also an acquaintance of Tarisio, drawn to his exotic personality, the ‘ephemeral insect’ as he described him. Reade dabbled in violin dealing, on some occasions acting as an agent for both Tarisio and Hart, but sometimes alone. The 1732 Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ that bears Gillott’s name was first owned by Reade, who sold it to Hart and thence to Gillott. The 1699 ‘Crespi’ Stradivari seems to have passed from Tarisio to Reade and then to Gillott.

Many of the instruments of the Gillott collection have no proven prior history, but it might well be assumed that Hart, Reade and Tarisio were the most common supply route. For the 1686 ‘Nachez’, 1717 ‘Whitney, Park, Gillott’, 1727 ‘Gillott’, 1737 ‘Lord Norton’ Stradivari violins, the 1672 ‘Mahler’ and 1734 ‘Gibson’ Stradivari violas, and the Andrea Guarneri ‘Primrose’ viola and 1755 ‘Berkova’ Guadagnini violin, Tarisio was almost certainly Gillott’s source, although there is no written record of this.

Luigi Tarisio was almost certainly Gillott’s source for the 1755 ‘Berkova’ Guadagnini among other instruments. Photos: Tarisio

More photosAlthough, according to his biographer, Eliezer Edwards, Gillott ‘had a quick ear for music’, [4] his interest in instruments was abstracted from their purpose; all accounts agree that those in his collection were never played, but were ‘strewn about his house and factory office’. [5] By around 1860 Gillott’s enthusiasm for instruments was on the wane. When Edwards offered him a Strad belonging to a friend ‘fallen on hard times’, Gillott told him: ‘Nay lad! I shan’t buy any more fiddles; I’ve got a boat load already.’ [6]

Indeed he had. The Christie’s sale catalog shows that, as well as the outstanding Stradivari, Amati and Guarneri examples, his collection included representatives of all the great Italian schools beyond Cremona: Testore, Grancino, Gagliano, Cappa, Montagnana, Guadagnini, Landolfi and Serafin all appear. There is also a remarkable concentration of Brescian works, including a Gaspar ‘da Salo’ bass cataloged as belonging to Dragonetti (although it is not the famous instrument that currently bears his name). Among all these are many English instruments, including a Barak Norman viol, two Forster cellos, two Urquhart violins, a Peter Wamsley cello, a viola by Vincenzo Panormo and several Dodd bows.

‘Nay lad! I shan’t buy any more fiddles; I’ve got a boat load already’ – Gillott

Also remarkable are names like Lupot, Vuillaume, Pique and Silvestre, several of which must have been relatively or even brand new when Gillott bought them. The auction catalog [7] was compiled by George Hart, the son of John who had originally supplied many of the instruments. It is surprising, then, that it contains a few significant errors. The 1727 ‘Gillott’ Stradivari was listed as a Panormo, and purchased by J.W. Joyce, a collector from Beckington, near Bath, for a mere £61. Surprisingly, the 1720 small Stradivari was identified only as ‘a very pretty small violin’ and bought by George Chanot for just £20. Other bidders at the sale included George Hart, Charles Reade and William Ebsworth Hill, newly arrived as a dealer in Wardour Street, London. He bought ‘an Amati cello’ for £22 and ‘a fine old Italian violin’ for £45, which may also have been an unidentified Stradivari. The highest prices were paid for the 1715 ‘Emperor’, for which George Hart paid £290, and a ‘del Gesù’ bought for £275.

The auction raised £4,195 9s 6d in total, probably worth around £5 million today. This does not account for the huge increase in violin prices over the most recent decades, and the result of a similar sale today would be almost incalculable. Individual items from Gillott’s collection might reach £10 million today.

Joseph Gillott (left) and one of his favorite haunts, the Hen and Chickens in Birmingham (right, photo: Birmingham Mail)

The sale of Gillott’s paintings extended over six days at Christie’s. Over 500 lots were sold, with his Turner collection offered on the fourth and sixth days. It raised £164,501, a sum equivalent to around £165 million today. Gillott was survived by eight children, and the need to divide up his fortune was probably the reason for the sale of his collections. The Birmingham Post noted at the time, however, that it was ‘a grievous loss to all lovers of art’, a lost opportunity for the city to acquire a grand collection of English paintings. [8]

The question remains how much of a connoisseur Gillott was, and how much a mere hoarder of valuables. Although blunt of speech and, by all reports, happiest in the bar of the Hen and Chickens with his churchwarden pipe, it would be wrong to assume a lack of genuine appreciation of the thousands of precious objects he accumulated. But it would also be wrong to assume that he cared any less about the financial returns on a smart investment.

John Dilworth is a maker, writer and expert. He has written extensively about fine instruments and their makers, and is a co-author of ‘The British Violin’, ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ and ‘The Voller Brothers’ among other books.

Notes

[1] George Muntz, successor to the firm, also acquired a Stradivari shortly after Gillott’s death, the 1736 violin which still bears his name, which he bought from Gand & Bernardel in Paris in 1874.

[2] Kenelm Foss, The Double Life of J.M.W. Turner, Seckler, 1938, p.174.

[3] Eliezer Edwards, Personal Recollections of Birmingham and Birmingham Men, 1877, Pinnacle Press, 2017, p. 33.

[4] Edwards, op. cit, p.34.

[5] Stephen Roberts, Joseph Gillott, and Four Other Birmingham Manufacturers 1784-1892, Stephen Roberts, 2016, p.16.

[6] Edwards, op. cit, pp.31–35.

[7] Catalogue of the Gillott sale, Christie Manson & Woods, Clowes, London, 1872.

[8] Peter Gay, Pleasure Wars, vol. V, W. W. Norton & Company, 1993, p.172.