Nearly a hundred years ago, on May 9, 1918, my great-grandfather, Baron Johann Ludwig Knoop, died at South Park, his large house in Wadhurst near Tunbridge Wells, aged 71. Virtually unknown, he had owned possibly the world’s finest collection of stringed instruments, including the ‘Lady Blunt’ and ‘Alard’ Stradivari violins, and at one point had in his possession two complete Stradivarius quartets. Seventeen instruments bear his name today, although ironically he never actually owned the 1698 ‘Baron Knoop’ Stradivari. In 1895 Arthur Hill of the dealers W.E. Hill wrote in his diary: ‘[Knoop] now unquestionably has the finest collection of stringed instruments in existence, and I doubt if any collection of the past is quite equal to his as regards quality’ (August 2, 1895).

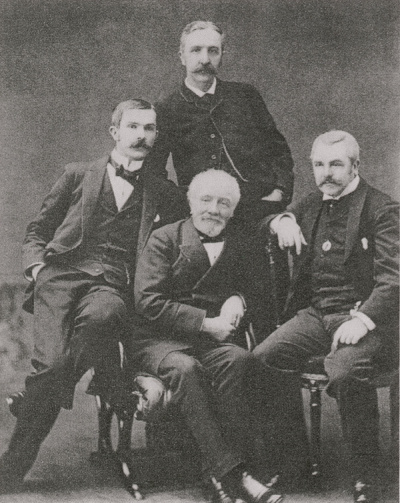

Ludwig Knoop with his sons at Mühlental (from left to right: Andreas, Theodore (standing), Ludwig and Johann

This is a story about a puzzle, about why this shy, unknown man assembled this amazing collection but then broke it up. The Hill business records and diaries show that he bought his first instruments in the late 1870s and between 1891 and 1899 added around 18 instruments, bringing the collection to about 20. On Sunday afternoons he and other amateur musicians would play quartets on these beautiful instruments. Yet after 1911 he bought no more, and by his death he had sold most of his collection.

Until recently little has been written about Knoop. Ernest Doring, writing in 1954, found it hard to gain information and it wasn’t until 2011 that Philip Margolis in an article for Cozio was able to fill in more details. As a descendant I have some different information from Margolis, and I am very grateful to Charles Beare, who has exceptionally given me access to the Hill diaries and has been kind enough to allow me to quote from them.

My mother was Johann’s granddaughter, but she never talked about him or his instruments, and for me this family silence is where the puzzle starts. Growing up in the immediate post-war 1940s I knew there was little family money, but upstairs in our house in Berkshire, almost hidden on a shelf in a passage outside the spare room, was a huge photo album with photos of a large white castellated house called Mühlental. Photos of the interior showed opulent rooms, portraits on the walls, music stands, a cello case. Others showed a beautiful garden with an ornamental lake, huge greenhouses and stables, and a grassy slope down to the river. On the same shelf another album contained photos of my mother as a toddler playing in that garden.

‘Ludi’ Knoop, son of Johann, with his daughter Adele, mother of Harriet Grace, in the grounds of the family house, Mühlental c. 1912

A few times in my childhood I flew to Switzerland to visit my maternal grandparents, Ludi and Emily Knoop, who lived in Montreux. I saw Ludi – the only son of Johann – for the last time when I was eight. He had shiny white hair and an intermittent cough, the last vestiges of childhood tuberculosis. I don’t remember having conversations with him, but at bedtime he would say very softly, several times, ‘Good night…. good night’ and then after a pause, very loudly: ‘GOOD NIGHT!’ which would make me shriek with laughter. Later I picked up that the family money had been lost in the Russian revolution, but I knew little more.

My knowledge, therefore, was connected to my great-great-grandfather, Ludwig, not to his son, Johann. This corroborates what Margolis says about the paucity of information on Johann. What we do know is that he had huge wealth, and it came from his father.

In Germany the eldest son in a family always had the same name as his father, so to distinguish the three generations I have given them the names they were known by:

-

- Johann Ludwig (1821–1894) called Ludwig

- Johann Ludwig (1846–1918) called Johann

- Johann Ludwig (1878–1959) called Ludi

Ludwig was born in Bremen, Germany, on May 15, 1821 and aged 17 was sent to Manchester to work for the cotton dealers, de Jersey & Co., run by members of his family. At 18 he went to work for the firm’s agents in Moscow and by 1840 had established the first power-driven cotton mill at Nikolskoye near Moscow. Over the next 25 years Ludwig set up between 100 and 200 cotton mills in Russia (Margolis). In 1857 he built Kränholm Mill on the Estonian–Russian border, the largest cotton spinning mill in Europe, and in 1877 in recognition for his work he was created a Baron by Tsar Alexander II.

Johann was Ludwig’s second child and first son. He was born on July 22, 1846 in Moscow and lived there with his five siblings. Ludwig had met Louise Hoyer, his German wife, in Moscow and they were part of the Russian–German community there. According to Johann’s sister Adele Wolde (Ludwig Knoop: Errinerungsbilder aus Seinem Leben, 1928) it was a happy childhood. Their father was good-natured and their mother was musical and played the piano. All the children learned the piano and Johann learned the violin too; according to Arthur Hill (May 13, 1918) he ‘played the violin very well and loved music.’

Then at about 12 he was sent to the trade school in Eschenhof, Bremen (Margolis). His grandparents and other relations lived there, but with his Russian background he must have seemed different to the other boys. His parents moved to Bremen in about 1859 and Ludwig bought land in St Magnus, a small village outside Bremen, where he built Mühlental on the slopes of the river Lesum, which was to become a focal point of Ludwig’s large family and a celebration of his achievements. Meanwhile Johann had three years of apprenticeships in Bremen companies (Margolis), and his two brothers, Theodor and Andreas, probably followed the same route. But afterwards Theodor and Andreas returned to work for the business in Moscow, whereas Johann appears to have spent time in Paris in 1867 with George Wolde, who would later marry his sister Adele, (Margolis and Wolde) and by the 1870s Johann was living in England. Johann thus grew up in various places and presumably spoke several languages – Russian, German, English and French – but I wonder where he considered home.

Schloss Mühlental, the mansion built by Ludwig Knoop at St Magnus, near Bremen in Germany, in the 1860s

Ludwig’s business was run entirely by members of the large Knoop family. According to Carl Albrecht, descendant of Johann’s sister Louise, Ludwig put his second son, Theodor, in charge of the Moscow office, his youngest son, Andreas, in charge of Kränholm Mill in Estonia, and Johann in charge of the much less important London office, a branch of de Jersey & Co. It is unclear why his father did not choose him to follow in his footsteps. There is no record of how Johann felt about this, but being the eldest son of a successful man was probably not easy and it seems that Johann had a different personality: quieter, more introverted and musical like his mother.

On September 22, 1874 Johann married Margarethe Kern at Mühlental and by 1876 they were living in Forest Hill, London. Johann’s daughter, Marie Louise, was born in 1875 and his son, Ludi, in 1878. Life must have seemed good. But in 1882 while they were staying at Muhlental, Margarethe contracted TB and died within six weeks on May 13, aged 26. Both Johann’s children also contracted TB and exactly eight years later, on May 13, 1890, Marie Louise died in Cairo aged nearly 15. Ludi continued to be ill, meaning that he was educated by a governess and never went to school, and only fully recovered as an adult. Then in 1893 the family gathered at Mühlental to celebrate Ludwig and Louise’s golden wedding anniversary. On that day Louise disguised the beginning of ill health and died of TB on January 26, 1894, followed by Ludwig on August 16 of the same year, also of TB (Adele Wolde).

All his life Johann was a collector. He collected carriages and clocks and was said to employ a servant just to wind the clocks

All his life Johann was a collector. He collected carriages and clocks and was said to employ a servant just to wind the clocks (Nicholas Knoop, letter to D.J. MacLeod, September 1995). Collectors have all sorts of motivations: owning something beautiful, the hunt, the growing expertise, completing a set and, in Johann’s case, playing and hearing music from his instruments. Maybe for Johann the instruments were also a substitute for relationships – something he could love and keep for as long as he wanted, unlike the lost members of his family.

Johann started collecting instruments in the 1870s before these bereavements, and continued collecting through them, until the end of the century. The Hill records indicate the earliest purchases were in 1882, the year his wife died, when he bought the 1701 ‘Court Strad’ violin and the 1735 Guarneri ‘King’ violin. However, Arthur Hill writing after Johann’s death (May 13, 1918) recalled that ‘it was in March of 1876’ that he personally delivered ‘the beautiful Landolphus violoncello [Knoop] bought off us for £55.’

In the same entry Arthur Hill talks about how Johann started collecting: ‘The Baron who first saw the light in Russia was German in his tastes…’ indicating that Johann’s interest in fine instruments went back to his early life, possibly as far as the late 1860s. Hill continues: ‘… it was through a German, C.G. Meier, and a set of wealthy German merchants interested in music also living in the S.E. District [sic], that we [the Hill brothers] first came in touch with him.’

In April 1898 Johann went to Russia with Alfred Hill to see the collection of instruments belonging to Prince Youssapoff, ‘a great collection which has been locked up for years and it has not been seen by any dealer or connoisseur’ (Hill diary, April 23, 1898). On December 30, 1898 Arthur Hill reports that Johann is going to fund a scholarship at the Guildhall School of Music. The Hill records show he bought a couple of instruments in 1901.

Then in 1902 Johann wrote to Arthur about selling the instruments (letters from Knoop to Arthur Hill) and an entry in the Hill diaries in 1904 states that they have sent Johann a cheque for £5,200 for two violins, the ‘Alard’ Strad and the ‘King’ Guarneri. Arthur never thought Johann would part with any his violins but writes: ‘However, various changes have taken place with Baron Knoop and we cannot help thinking that possibly the war in the East may have something to do with it.’He goes on to say that Johann ‘promises that the whole of the instruments in his unique collection shall come back to us.’

In 1903 Knoop and his family moved into South Park, a mansion in Sussex, Southern England

These changes were probably not due to the 1904–05 war between Russia and Japan, referred to by Hill, but for two reasons rather closer to home. First, he started spending money in different ways; and second, he married a much younger woman, Mabel C. Stuart King (1875–1945), known as May or Maya. Around 1900, apparently in gratitude for Ludi’s full recovery from TB, Johann put money into developing a sanatorium called Al Hayat at Helwan, south of Cairo. The exact nature of Johann’s involvement is unclear, but it was clearly expensive. Arthur Hill reports (December 18, 1920): ‘In the conversation, she [Maya] told Alfred that they all regretted the dispersal of the Baron’s collection of fine instruments, which were sold to find the money for the sanatorium founded by him at Helouan [sic], of which institution, I understand, he was eventually cheated.’ Also in 1903 he moved into South Park, a mansion in Sussex, and seems to have spent a lot of money doing it up. There was also Mühlental plus, reputedly, a yacht in Egypt and some kind of residence in Paris.

‘[Maya] told Alfred that they all regretted the dispersal of the Baron’s collection of fine instruments, which were sold to find the money for the sanatorium’ – Arthur Hill

Johann first met Maya in 1893. She was 18, he was 47. Margolis uses two sources to describe this relationship, both sympathetic towards Maya: Mike Ashley’s biography of her friend Algernon Blackwood (1869–1951); and the autobiography of Stephen Graham (1884–1975), ‘Part of the Wonderful Scene’, who was another close friend of Maya. These sources agree that Johann saw Maya playing the violin in a quartet in Vienna and became ‘entranced’. She became Ludi’s governess and married Johann in July 1899. From these sources Margolis paints a picture of a beautiful young woman, ‘possessed’ and mistreated by Knoop, who kept her in black servant’s clothes and took away her Stradivari violin. This continued until she read Nietzsche, whose advice was to ‘Be hard as a diamond’. From then on she took charge of her life and appeared to enjoy living in large houses in England and Germany, spending winters in Egypt and having a very close relationship with Blackwood, who from 1911 frequently stayed in one of the cottages at South Park and dedicated his books about the supernatural and occult to her.

My immediate family never spoke about Maya, and hearsay among my other relations was that she was not popular. There is a family anecdote that she made a pass at Ludi when he was in his teens and that when he refused her she warned him, ‘Watch out, I may marry your father.’ Arthur Hill reports (March 5, 1930) that after Ludi became bankrupt, Maya, who had married and was widowed again, ‘refrained from even writing to her stepson on his trouble.’

The relationship between Maya and Blackwood flourished during the last few years of Johann’s life, when according to Ashley ‘he was an invalid’ and had ‘all his life had been something of a hypochondriac’, perhaps not surprising considering the numbers of his family who had died of TB. Ashley goes on to say, ‘despite his wealth he was seldom happy and spent much of his time in seclusion. Maya, on the other hand, though petite, was full of life, a bundle of energy, always laughing and gay’. Whatever the truth about their marriage, it appears to have had a profound effect on Johann. It seems he became preoccupied with huge expensive projects and dropped the thing he loved – music and musical instruments.

‘Today Alfred and I had the painful experience of attending… the Cremation of our good friend, Baron Knoop, who… was the best client our firm has had’ – Arthur Hill

In the early years of the 20th century Russian anti-German feeling was building. In January 1916 the name of the office in Moscow had to be changed from L. Knoop & Co to Volokno (meaning fibre), and in 1917 the revolution wiped out most of the Knoop empire. All the mills in Russia were taken, leaving only de Jersey & Co. in Manchester and the Kränholm Mill in Estonia, both with a hugely reduced market. Johann died not long afterwards, on May 9, 1918. Arthur Hill wrote (May 13, 1918): ‘Today Alfred and I had the painful experience of attending at Golders Green the Cremation of our good friend, Baron Knoop, who, with the exception of Mr. Richard Bennett, was the best client our firm has had, and who we have known all the best years of our lives.’

In his will dated 1913, before the loss of his wealth, Johann left South Park for Maya to live in, a very adequate income to her and her relations, and all his musical instruments. Ludi was left family pictures and photographs including ‘paintings of violins’, plus the ownership of the house should Maya chose to move or marry again. Maya moved immediately but the house proved difficult to sell. Ludi was also left Mühlental, which was to become a huge burden and eventually had to be pulled down in 1933. It is now the beautiful Knoop Park containing a stone footprint of the house. In 1930 de Jersey & Co. was wound up with creditors owed around £750,000. Ludi was left with £40. Emily, his wife, wrote to Arthur Hill on February 3, 1930: ‘Ludi knows that you, as an old and good friend, will do all in your power to help him in his terrible trouble.’ Arthur Hill wrote in his diary (March 5, 1930): ‘Baron Ludi is now constrained to part with everything he possess in order to meet the demands of the creditors of his firm in North of England who are clamouring for money. He is therefore anxious to get as much as possible for the Amati quartet and the Montagnana cello.’ Thus the remaining instruments were sold. Ludi and Emily moved to live in hotels in Europe, paid for by Emily’s American parents. They fled to Switzerland in 1939, where Ludi lived for the rest of his life in the Hotel National, Montreux.

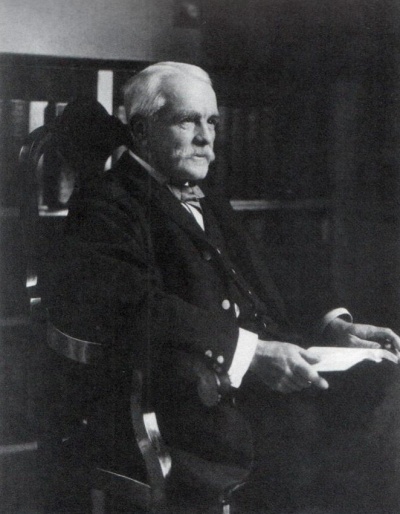

Johann Knoop ‘was the best client our firm has had,’ recorded Arthur Hill after Knoop’s death in 1918

The Russian Revolution was a catastrophe for the Knoop fortunes and maybe what I felt as a child was the huge aftershock: the pain of losing the world they knew, the guilt of Johann at not seeing what might happen and taking action to mitigate it, the shame of descending from riches to rags, the confusion about their identity and whose side they were on during two world wars – Germany, Russia or England. Maybe these things were enough to feel that silence was the only possible response. Everyone wanted to forget.

In 1986 the Russian government decided to compensate the companies and people who had lost money in the revolution. This led to the reinstatement of de Jersey & Co. and a small amount of money for the descendants. It put us in touch with Knoop relations, and in particular Nicholas Knoop (1916–2001), grandson of Andreas, who has helped to fill in many details. It brought me nearer to Johann, and made me aware of his extraordinary life and collection. Glancing now at a photograph of Johann, with his high forehead, white hair and moustache and the gentle – it seems – look in his eyes, I feel I have got to know him a little.

Johann Knoop may have been obsessive, shy and a recluse in his latter years, but he had to cope with a tumultuous life, right up to the last few months. What he couldn’t know is that his passion for collecting so many priceless instruments would mean that the global musical community would know his name a hundred years after his death.

Many thanks to Charles Beare for access to and permission to quote from the diaries of Arthur Hill, to my cousin Monique Dubois for providing photographs, to Carl and Harald Albrecht, and to Aard van Kollenburg.

Harriet Grace is a writer and career counsellor; her published work includes the novel ‘Cells’.

|