Daniel Müller-Schott

For some reason I have always been drawn into the sound world of Venetian instruments. I tried cellos for more than ten years before I found this one – all the Cremonese makers and different Venetian ones too, from Guarneri, Montagnana and Stradivari to Grancino, Tecchler and Testore, and I always ended up with Goffriller.

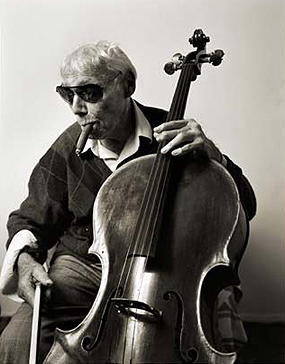

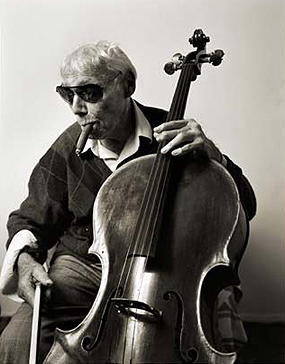

I found this cello in 2006. I was playing an earlier Goffriller and I had a concert in New York. The owner of this cello happened to hear me on the radio and through a mutual friend, the violin maker and dealer Christophe Landon, he invited me the next day to try it. That was how I met Harvey Shapiro. He was then over 90 years old and he must have had the Goffriller for over 60 years. Harvey told me the story of how, when he was in his 30s, he went to the New York violin shops and all the cello dealers and he had the opportunity to get either the ‘Hausmann’ Strad or a Montagnana or a Goffriller and he picked the Goffriller in the end because of its sound qualities.

It’s like boiling oil – a very intense sound

What hit me at first was the aliveness of the sound that it produces. It’s like boiling oil – a very intense sound. It was something I had never heard before. My other Goffriller was also a very good instrument but it didn’t have that aliveness. Harvey told me I should take it to a bigger space so I would realise what sound it was able to produce. So I took the cello to Carnegie Hall with some other musicians who also brought their instruments to compare, which was very helpful. And it was really love from the first tone.

Harvey Shapiro believed that the cello sounded best if you smoke Havana cigars

Unfortunately I didn’t have the opportunity to try it for longer, but I kept a sound picture of it in my head when I went back to Germany and I knew that this would be my cello. It took me four weeks to find someone to help me with the financial part and then the cello was brought to me from New York, curiously enough together with a cigar box, because Harvey Shapiro believed that the cello sounded best if you smoke Havana cigars. He was always smoking them when he gave his masterclasses and the cello really smelled of the smoke – that unmistakable Cuban smell of Havana cigars. I still have the box of cigars and keep it next to the cello!

My previous Goffriller was an earlier instrument that had been cut down so it was slightly slimmer and it didn’t have the same bass support that this instrument has. This one is still the original size and it’s slightly wider and bigger overall. The previous one was dated 1700 and this one is from 1727 and I think this model shows a more experienced concept.

The sound of the cello has changed over the years. When I got it the sound was a little more harsh although it was always very characterful. Now the character is still there but it has more silky and brighter, singing qualities. There is this great mixture of warmth, generous volume and yet an incredible centre that always makes the sound speak to you. It’s a voice that doesn’t leave you unaffected.

I’m fascinated how you change as a player and how you also change the instrument through your playing. This cello has a breadth and generosity of sound that really opened up a lot of emotional expression in me. It supports me so much when I play with symphony orchestras because I never feel that I have to force myself. The instrument gives so much by itself.

I have experimented with the set up in order to find the perfect balance. The ring of the instrument has to be as free as possible and of course each instrument reacts differently. I’m very grateful that I have a wonderful violin maker who’s also a cellist – Dietmar Rexhausen in Germany – and I’ve experimented with him a lot over the years.

My strings were made especially for the cello by Laurits Larsen and his team at Larsen Strings. They heard me play with an orchestra in Denmark and afterwards we got into conversation about the sound of the cello, and they were inspired to make a set for me. I wanted strings that balance out the different registers of the cello. For example if a string is too strong then it weakens the top register and if it’s too weak then it doesn’t make it ring as freely as I want – it’s a very sensitive balance, but now I’m really happy with the result.

My Goffriller is named the ‘Földesy’ after the Hungarian cellist Arnold Földesy, who owned it in the early 20th century. I first came across his name in Gregor Piatigorsky’s autobiography. He talks about Földesy being quite a wild, temperamental guy but he says that he liked Földesy’s Goffriller – so Piatigorsky also knew my cello. It has been in good hands!

Interview by Naomi Sadler

Daniel Müller-Schott, Wigmore Hall Friday 15 September 2017