This previously unpublished letter written by Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume, which will be auctioned by Tarisio in London this month, reveals the difficulties experienced by the Parisian violin dealer during the dramatic political upheavals of 1871.

The recipient, Monsieur Eugène Fau, was an established French violin collector who owned one of the ex-Castelbarco Stradivari cellos, a 1716 Stradivari violin, and the ‘Violon du Diable’ by Guarneri ‘del Gesù’. He seemed to have wanted to own a complete quartet of 18th-century Cremonese instruments, and this may be the ‘request’ to which Vuillaume refers. [1] Fau also has the distinction of being the person to whom Vuillaume offered the ‘Messiah’ Stradivari in 1865, according to the Hills in their book Antonio Stradivari: His Life and Work – apparently in an effort to show evidence of the increase in value for Stradivari instruments on the Continent. [2]

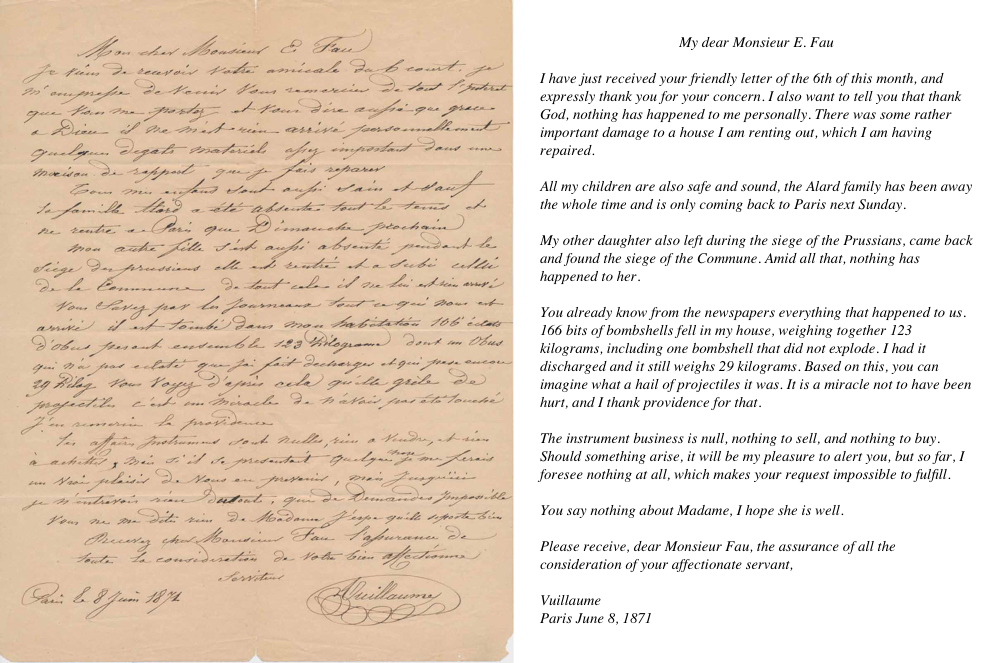

Vuillaume’s letter to Eugène Fau was written just a week after the end of the Commune

‘166 bits of bombshells fell in my house… you can imagine what a hail of projectiles it was. It is a miracle not to have been hurt’

The letter was written a week after the end of the Paris Commune, a particularly bloody period in the political history of France. Less than a century after the French Revolution, the people of France had rebelled against the established government once more. Following the defeat of Emperor Napoleon III against the Prussians in 1870, the troops of the National Guard refused to accept the establishment of the Third Republic, which was still at war with Prussia. Paris was then ruled by the Commune, a radical socialist movement, from March to May 1871, in a period which some consider the first expression of anarchy.

The barricades of the Paris Commune, 1871. Left: the rue du Rivoli, by Pierre-Ambrose Richebourg; right: the Place Vendôme

Many bourgeoise families fled Paris, including the Alards and the Vuillaumes. Jean-Baptiste, however, decided to stay in Ternes, which is now the 17th arrondissement, close to the Arc de Triomphe, where the newly proclaimed German soldiers marched in March 1871. Two weeks later the Commune started, leading to the barricades, the ‘semaine sanglante’ (the bloody week) and the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine by Germany in May.

The revolt was eventually suppressed by the French army, culminating in the massacre of the last resisting Commune troops at Père-Lachaise Cemetery on May 27, and the Commune finally ended on May 28. We know from Georges Chanot’s accounting books that ‘business starts again’ on July 1, but remained meagre until December. This would explain why, on June 8, Vuillaume has ‘nothing to sell’. Surprisingly, however, the production of his workshop does not seem to have been particularly affected, with 34 instruments produced in 1869, 24 in 1870, 52 in 1871 and 39 in 1872, according to his workshop ledger. [3]

In her book Jean Baptiste Vuillaume et sa Famille, Sylvette Milliot follows Vuillaume’s life through the letters he wrote to his family, vividly recounting the events of these difficult times. However, she reports a large gap between the beginning of the Commune in March 1871 and December 9, 1871. This letter therefore helps bring to light a particularly dramatic episode in Vuillaume’s life.

The letter is Lot 1 in Tarisio’s London October auction.

Notes

[1] John Dilworth, The Strad, September 2002, p. 973.

[2] W.H., A.F. and A.E. Hill, Antonio Stradivari. His Life and Work (1644–1737), W.E. Hill & Sons, 1902.

[3] Sylvette Milliot, Les luthiers parisiens aux XIXe et XXe siècles: Jean Baptiste Vuillaume et sa Famille, Amis de la musique, 2006.