By the end of the 19th century Turin was at a junction between two quite different eras. In 1859 it was the capital of a nation and its largest city. By 1870, with the final unification of the Italian peninsula, it had ceded its capital status to Rome, and its population, which had always been smaller than that of Milan, Naples and Rome, made it just a mid-sized Italian metropolis. Its opera house was still justly famous, but was now overshadowed by the much more celebrated La Scala in Milan. However, its role in the nascent automobile and aviation industries was beginning, and the city remains a great industrial center to this day.

It was similar with violin making. In the late 19th century the most important shops were those of the Guadagnini, last of a celebrated dynasty, and that of Rinaldi, heir to the Pressenda tradition. Violin making in the next century would be dominated by two figures, neither of them, however, from the old traditions.

Annibale Fagnola (1866–1939) was a native of Montiglio, near Asti, and worked briefly as a baker there before leaving for Turin in 1894. He arrived at a time of flux: the Guadagnini shop was in transition after the death of Francesco’s mother, while Marengo-Rinaldi had just assumed directorship of the Giofredo-Rinaldi shop. Enrico Marchetti had recently moved away and the elderly Enrico Melegari was in his final months of life. According to correspondence from Rembert Wurlitzer, who met Fagnola in the early 1920s, he was actually self-taught, a remarkable achievement.

Fagnola’s first documented instruments were guitars, but he quickly began to make violins, and it was with these instruments, sold in his own shop and through agents in London and elsewhere, that he quickly gained celebrity as one of the finest makers in Turin. In 1906 his instruments were praised and rapidly sold when they were displayed at the International Exposition held that year in Milan. He also earned a gold medal for a quartet he submitted to the Exposition in Turin in 1911.

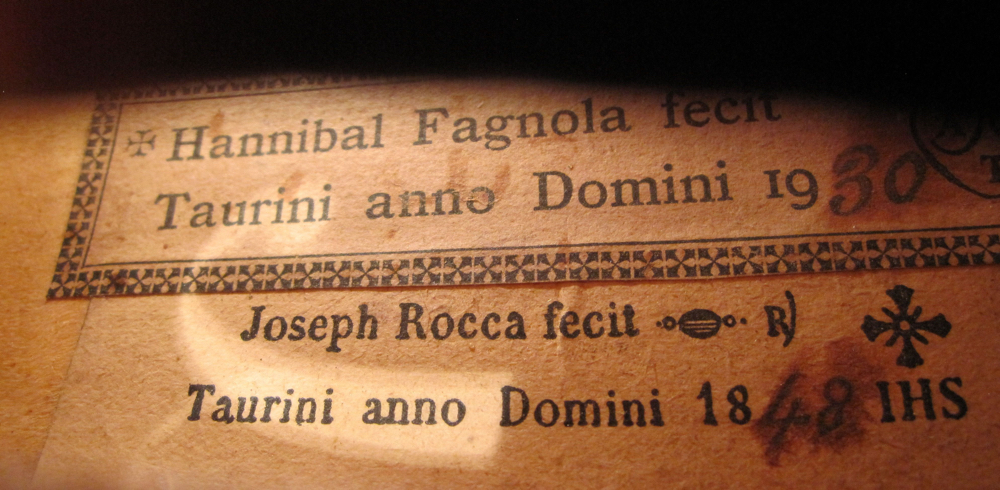

The label of the Fagnola above shows his practice of using double labels, with a facsimile copy of the label of his model. Photo: Tarisio

The earliest Fagnola violins were personal interpretations of the Pressendas and Roccas he would likely have seen locally. Over time, his production settled into a pattern of what he termed ‘models’ and ‘copies’. The models were invariably the same three: Pressenda, Rocca and a Guadagnini violin of 1773. These he made as straight ‘new’ instruments, with smooth finishes. They always bore his own label as well as a facsimile of a label of his model, and he signed and dated the interiors, in time always on the upper bass ribs. His copies were the same as the models, but with antiqued varnish to imitate the originals. In some of these instruments the maker’s own labels were removed by the unscrupulous so that they could be presented as ‘authentic’.

Fagnola’s shop remained active up to his death, just a month and a half after the onset of World War II. Because of the cut-off of communication between England, his leading market, and Italy during the war, word of his death did not reach the rest of the world until many years later, his actual death date being published only in the 1990s.

Because of the cut-off of communication between England and Italy during the war, word of Fagnola’s death did not reach the rest of the world until many years later

A number of fine makers received their training under Fagnola, most notably Riccardo Genovese (1883–1935), who was the only Fagnola student to make an appreciable number of violins. He was a native of Montiglio and spent almost his entire life there, except for a period in which he worked in the town of Lecco. A mattress maker and pianist by profession, he may have come to know Fagnola in the early 1920s, and by 1922 declared himself to be a violin maker. His career was not very successful financially, but a number of fine instruments exist from the 1920s that attest to his skill.

Fagnola trained his nephew Anibalotto Fagnola (1910–1984), who made a very small number of violins. He also probably trained Stefano Fasciolo (1878–1944), a professional cellist who seems to have worked with him during the 1930s, after Anibalotto had left for military service.

A 1905 violin by C.G. Oddone, whose prolific output ran to well over 250 instruments. Photos: Tarisio

More photosThe other maker who dominated the trade in the 20th century had a rather different background. Carlo Giuseppe Oddone (1866–1935) was the same age as Fagnola, but early in his career he went to work for Giofredo Rinaldi. After Rinaldi’s death, on the references of Rinaldi’s widow, he was able to gain employment with Frederick William Chanot, a son of George Chanot Jr., who was both a violin maker and music publisher in London. He worked for Chanot for two years from 1889, gaining valuable experience in the sophisticated and disciplined French methods of the Chanots and in observing fine instruments. After his return to Turin he opened his own workshop in 1892, but it is believed that he continued to produce work for both Romano Marengo in the Rinaldi shop and for Enrico Marchetti. This included not just instrument making but also restoration, in which he was particularly skilled. After a brief return to London in 1899, he settled permanently in Turin and remained there until his death.

Oddone’s distinctive brand stamp

Unlike Fagnola, Oddone followed a number of different models, including Pressenda, Rocca, Guadagnini and several variants on Stradivari, Amati and Guarneri. His approach to ‘del Gesù’ was strongly influenced by the Chanot family models. His earlier varnish was more experimental and could be red, orange, gold or brown, depending on the maker whose work was being followed, but in later years he stuck to a distinctive golden-yellow for almost all of his work. All told he made well in excess of 250 instruments, which he began to enumerate only after 50 or so had been sold. He also adopted a distinctive brand that was placed around the end button as well as inside on the blocks, the back and the top.

Of the other makers who continued to ply the craft in Turin before World War II, Francesco Guadagnini and his son Paolo have already been discussed in part 3. Enrico Marchetti (1855–1930), also mentioned in part 3, opened his own workshop in 1881 and competed in various expositions with the aim of establishing his reputation. His labels thereafter referred to the 15 medals he had received in Italy and other countries. In 1894 he moved to Cuorgnè for almost 20 years. On his return to Turin he continued working much as before right up until his death.

Marchetti trained his son, Vittorio Edouardo Marchetti (1882–1930), who worked independently of his father for a period but died shortly before him. At the end of his life he took on Anselmo Curletto as a pupil.

Romano Marengo (1866–1926) was a native of Alba, where his father, a carpenter by profession, had worked on the organ in the cathedral. He later came to Turin, where he went to work for Giofredo Rinaldi and learned the craft from Rinaldi’s occasional employee Enrico Marchetti. After Rinaldi’s death, Marengo began to work with his widow in the shop, eventually buying it out and running it under the name Marengo Rinaldi. The shop was well known and respected, engaging primarily in dealing and repairs, as had the earlier Rinaldi shop, but it did not survive Marengo’s death.

Anselmo Curletto (1888–1973), having trained with Marchetti, established his own workshop in the town late in the 1920s. His work was very much influenced by that of his teacher. Arnaldo Morano (1911–2007), the last significant maker of the Turin school, received some of his early training in his workshop. He settled in Rosignano Monferrato after World War II.

Enrico Marchetti violin from 1908. His labels refer to the medals he won in various competitions to establish his reputation

More photosFour other Turin makers stand out during these years: Emilio Evasio Guerra, Luigi Azzola, Giorgio Gatti and Plinio Michetti. Guerra (1875–1956) is believed to have worked with both Fagnola and Oddone during the years that each was gravitating to the Marengo Rinaldi shop. While he was a highly capable maker, he was less talented in business and thus spent most of his career working for the other shops in town. The excellence of his work, though, is such that he is regarded as among the finest makers of the period.

Azzola (1883–1973) might have been Fagnola’s last assistant, for he lived at Fagnola’s address from around the latter’s death until 1944. He was a fine maker but made few instruments that have survived.

Gatti (1868–1936) was a man of some means who came to Turin from his native Chieri in 1890. He may have worked briefly with Marchetti, opening his own shop on Marchetti’s departure for Cuorgnè, but there is little similarity between their work to suggest that Gatti received much in the way of instruction. During the first part of his career he apparently engaged in both instrument making and flours and grains. His work is distinctive, ostensibly based on Pressenda but often showing an odd elongated F that suggests late ‘del Gesù’ as much as anyone else.

Lastly, Michetti (1891–1991) was from near Savona, on the Mediterranean, where he received some training from Euro Peluzzi, a maker best remembered today for having written an early primer on violin making. He came to Turin around 1925 (a violin of 1924 signed from Savona is known) to work for a local music shop, making instruments for them and probably for his own account. They are of fine quality, showing a Genoa influence in their construction as well as that of Turin. He died aged 100, and his family is still engaged in the violin trade.

Philip J. Kass is an expert on classical violin making and has contributed extensively to the Journal of the Violin Society of America, The Strad magazine and the New Grove Dictionary of Music. The first three parts of his series on the Turin school are also available to read as Carteggio features:

Part 1: 1650–1770

Part 2: the Guadagnini family

Part 3: the 19th century