In the 19th century Belgium punched above its weight musically in the Franco-Belgian violin school, and one of its chief champions was Henri Vieuxtemps. When Vieuxtemps introduced his E major Violin Concerto in Paris in 1841, Berlioz wrote: ‘He does things that I have never heard from any other; his staccato is brilliant, delicate, radiant, dazzling; his double-stop singing rings extremely true.’ [1] Vieuxtemps also played this concerto for the Philharmonic Society in London, leading one critic to call him ‘the Beethoven of all the violinists known to us’. [2]

Born on February 17, 1820 in Verviers, a Walloon town in Liège province, Vieuxtemps was ten by the time Belgium achieved independence in 1830. His father, a weaver who played the violin in his spare time and also made fiddles, was his first teacher but soon passed the four-year-old on to the excellent violinist Joseph Lecloux.

Portrait of Henri Vieuxtemps in 1828 by Barthélemy Vieillevoye. Image: Wikimedia Commons

At six Henri played Rode’s Fifth Concerto and a Fontaine Air Varié in public with orchestra; the following year he went on tour with his father and teacher. When he played for the Grétry Society in Liège on 29 November 1827, he was presented with a François Tourte bow – the first of many such gifts over the course of his career.

In Amsterdam the boy was heard by Charles de Bériot, who got him a scholarship from King William of the Netherlands and took over his tuition. It was probably at this point that Vieuxtemps obtained his first quality violin, the 1618 Brothers Amati that still bears his name and is now part of the Smithsonian collection. Originally small, it was enlarged at some stage and Nicolas Lupot has been suggested as the maker responsible. However, this is highly unlikely as Lupot died in 1824 and the young Vieuxtemps – who even in adulthood would be a slight figure – needed a small violin.

The family moved to Brussels, where Vieuxtemps became de Bériot’s protégé. ‘De Bériot was a second father to me,’ he recalled. [3] At one of de Bériot’s Paris concerts in February 1829 Vieuxtemps played Rode’s Seventh Concerto, inciting François-Joseph Fétis to write that he ‘possesses an assurance, an aplomb and a precision truly remarkable for his age; he is a born musician’. [4]

In 1831 de Bériot left for Italy and from then on Vieuxtemps taught himself, although he was influenced by Louis Spohr. The next winter he spent in Vienna, where on March 16, 1834 he played Beethoven’s Concerto, having learnt it in 15 days. The first performance of the work in the city since the composer’s death, it caused a sensation.

Vieuxtemps in 1846. Image: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, via Wikimedia Commons

Vieuxtemps’s tours with his father took him to Russia in 1837 and 1839. He was taken up by musical scions of the Russian and Polish nobility such as Prince Alexei Lvov and Prince Nikolai Golitsyn. He played Beethoven quartets with his noble friends and also got to know Glinka, Dargomyzhsky, the Polish violinist Karol Lipiński and German pianist Adolf von Henselt.

Through Count Mathieu Wielhorski, Vieuxtemps was appointed court violinist to Tsar Nicholas I, soloist in the Imperial Theatres and teacher of music classes in St Petersburg, where he lived from September 1846 to September 1852. He also taught many Russian aristocrats who were keen amateur musicians, and his pupils included Prince Nikolai Yusupov.

By this time the violin making hierarchy was established, with Stradivari at its apex and Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ often the connoisseur’s choice. Yet although such artefacts were regarded as costly, their prices had not yet become inflated. Music-loving aristocrats, especially in Russia, often owned dozens of Italian fiddles. So popular was Vieuxtemps with the Russians that fine instruments were showered upon him: according to his biographer Lev Ginsburg, they included three Stradivari violins, one from Lvov and two from Count Stroganov; three Amatis – a violin, a viola d’amore and a cello – from Wielhorski; and a Maggini, which he played a lot, from another aristocrat named Wolkoff. [5] We can identify the Stroganov Strads as the 1710 ‘Vieuxtemps’ and, also from 1710, the ‘Vieuxtemps, Hauser’.

The ‘Vieuxtemps, Hauser’ Stradivari of 1710, presented to Vieuxtemps by the Russian Count Stroganov. Photos: Tarisio

More photosVieuxtemps was also presented with another Tourte bow by the Demidov family at the Tsar’s request, and acquired six (possibly seven) bows by the celebrated St Petersburg maker Nikolai Kittel.

In 1844 Vieuxtemps had married Viennese pianist Josephine Eder, his faithful partner on stage and off until her death. And it was in Vienna two years later that a patron gave him a Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, labeled 1743 but dated to c. 1741 and now known as the ‘Vieuxtemps, Wilmotte’. Vieuxtemps said this violin’s ‘exquisite qualities’ helped him with the conception of his D minor Concerto, [6] described by Berlioz as ‘a magnificent symphony with principal violin’. [7]

Of several ‘del Gesù’ instruments associated with him, he played the ‘Vieuxtemps, Wilmotte’ the longest, finally selling it in around 1870 to the collector André Wilmotte. In 1878 he described it in a letter to Wilmotte as ‘one of the master’s beautiful specimens, and of a powerful and sympathetic sound, all at the same time’. He concluded the letter: ‘I am delighted, my dear Wilmotte, to know that it is in your hands… From now on I shall, on the one hand, be happy with its fate, and on the other hand, I congratulate you with all my heart.’ [8]

But his favorite Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ was the 1741 ‘Vieuxtemps’, which he bought from London dealers Hart & Son in around 1860. [9] He is likely to have used it for the first performance of his A minor Concerto, in Brussels in September 1861. Fétis, by then director of the Brussels Conservatoire, was most enthusiastic, as was Berlioz when Vieuxtemps played the concerto in Paris the following year. In an 1881 letter to cellist Joseph van der Heyden, Vieuxtemps described this ‘del Gesù’ as ‘a unique pearl’. [10]

The 1741 ‘Vieuxtemps’ Guarneri, which Vieuxtemps described as a ‘unique pearl’. Photos: Peter Biddulph Ltd

More photosVieuxtemps also possessed the c. 1744 ‘del Gesù’ on which the great Karol Gregorowicz later performed, but he had sold it to Wolkoff by 1870. Other violins in his large collection included a 1758 Guadagnini; a Milan period (pre-1740) Guadagnini, passed on to his pupil Madame d’Exarque and later played by Carl Flesch; a Lorenzo Storioni, which he used a good deal in the early 1860s; a Vuillaume dated 1874; and a 1700 Giuseppe Guarneri ‘filius Andreae’. He also loved playing on other collectors’ instruments such as the c. 1731 Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ owned by the Turettini family of Geneva.

Vieuxtemps was also a superb violist and owned a fine 1768 Guadagnini, now played by the Norwegian violist Eivind Ringstadt on loan from Dextra Musica. He also owned a Nicolò Amati until 1867, now part of the Henry Ford collection, and a Brescian instrument formerly attributed to Gasparo ‘da Saló’, which he sold to the Duc de Camposelice.

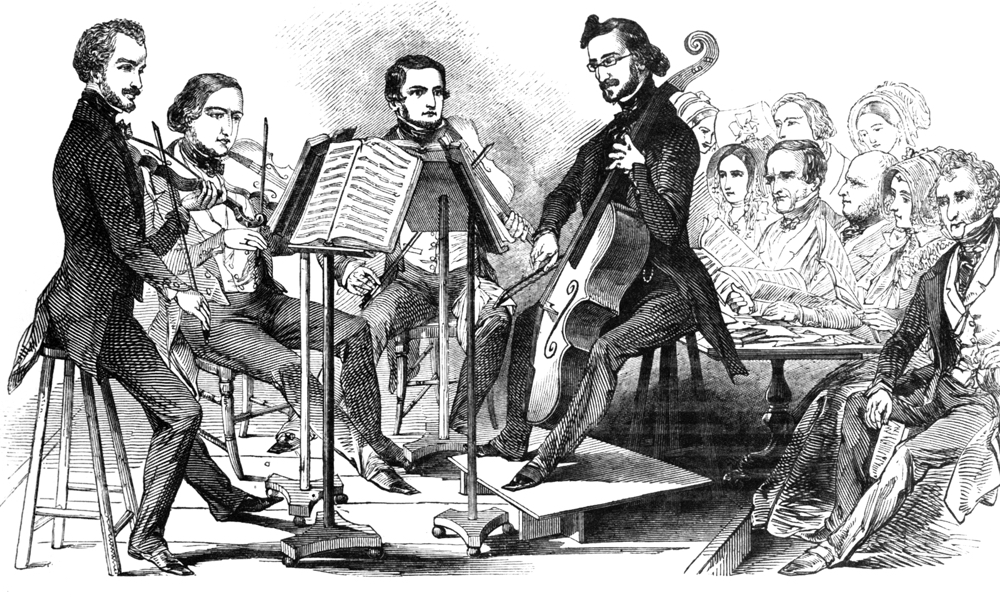

Even more influential in Russia than his solo concerts was Vieuxtemps’s quartet, with brothers Carl and Gustave Albrecht and Benjamin Gross: besides Haydn, Mozart, Mendelssohn and Schubert, they played Beethoven’s late quartets publicly in St Petersburg for the first time. Vieuxtemps also always played quartets on his London visits. An Illustrated London News etching shows him at the Musical Union in June 1946: Vieuxtemps sits on a high four-legged stool while opposite him Alfredo Piatti’s similar stool rests on a raised platform. Below them on chairs are second violinist Jacques Deloffre and violist Henry Hill (see image below).

From left: Henri Vieuxtemps, Jacques Deloffre, John Hill and Alfredo Piatti, with John Ella (far right) at the Musical Union in June 1946. Image: Tully Potter Collection

The death of his wife in 1868, from cholera, was a severe blow. A few years later Vieuxtemps plunged into a new job as professor at the Royal Brussels Conservatoire, but a stroke in 1873 disabled him. He recovered enough to compose – including two cello concertos and his last two violin concertos – and to play quartets at home, but finally resigned in 1879.

Vieuxtemps died on June 6, 1881 in Algeria, where he had gone for his health. His ashes were taken back to Verviers, where thousands lined the streets on August 28. The hearse was drawn by four black horses and his former pupil Eugène Ysaÿe walked in the procession, carrying the 1741 ‘Vieuxtemps’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ with one of the master’s Tourte bows on a black velvet cushion with silver tassels. It was rumoured that Vieuxtemps had even wanted to be buried with his Guarneri, but fortunately it did not meet with this fate. After his death it was played by Ysaÿe and later another Vieuxtemps pupil, Philip Newman.

Tully Potter is a journalist and music critic. He is a regular contributor to various international music journals and has written a biography of Adolf Busch.

Notes

[1] Lev Ginsburg, Vieuxtemps, His Life and Times, ed. Herbert R. Axelrod, trans. I Levin, Paganiniana Publications, New Jersey, 1984.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] John Dilworth, Ole Bull 2010: Guarneri del Gesu Collection, Dextra Musica, 2010, p. 29.

[7] Robert Riggs, ed., The Violin, University of Rochester Press, New York, 2016.

[8] John Dilworth, op. cit, p. 26.

[9] Terry Borman, ‘Unspoiled Charm’, The Strad, May 2018.

[10] Ibid.