Until a few years ago, Tommaso Balestrieri was thought to have been born around 1735. This was based primarily on his emergence as a violin maker in the mid-1750s, when he was assumed to have been in his late teens. However, recent research by Philip J. Kass has now placed his birth in the village of Viustino, south of Piacenza, on November 16, 1713, a mere two years after G.B. Guadagnini was born in the same region. This new research raised an interesting question – what was Balestrieri doing for 25 years from approximately 1730 to 1755, and how did this period affect his subsequent career as a violin maker?

Around 1730, at the age of about 17, Balestrieri left his family and moved to Mantua, where he worked as a valet to the Count Alberiggi di Quaranta, in all probability following in his father’s footsteps. For the next 24 years he worked as a servant for various noble families in Mantua, so what was it that prompted him to undergo such a sudden change of career in the mid-1750s?

In 1741 Balestrieri was in the employment of Count Giuseppe Malatesta Palazzi, who had inherited the instrument collection of Count Vincenzo Carbinelli. Carbinelli was a Mantuan nobleman whose extraordinary collection of fine Italian instruments included ten Stradivari violins, five Amatis and a Pietro Guarneri. The highlight of his collection was the decorated ‘Rode’ Stradivari of 1722. This contact with Cremonese violins may have been enough to inspire Balestrieri to embark on his new career as a violin maker, and by 1755 he had given up his life as a valet and moved into the via Cicogna, the same street where Pietro Guarneri had lived and where Camillo Camilli’s workshop was situated. It seems likely that Balestrieri had some contact with Camilli, although the latter had died in 1754.

The history of violin making in Mantua is undeniably distinguished, yet it was never a busy one. In fact, Mantua seems to have been the violin making equivalent of a one-horse town, unable to support more than one violin maker at a time. Pietro Guarneri arrived from Cremona in the early 1680s, and it was only after his death in 1715 that Antonio Zanotti emerged. Camillo Camilli worked very briefly as Zanotti’s apprentice and two Camilli violins bearing Zanottti’s original label are known, but after Zanotti’s death he was the only maker active in Mantua. Camilli died in 1754, and Balestrieri miraculously appeared on the scene soon afterwards, and was registered as a violin maker by 1758.

What was it that prompted Balestrieri to undergo such a sudden change of career in the mid-1750s?

Balestrieri’s early work bears the hallmark of the Mantuan tradition, dominated as it was by Pietro Guarneri. Balestrieri’s approach was certainly heavier than Guarneri’s and he was no match for him as a craftsman, but certain key features such as the thicknessing pin in the centre of the back, a tradition handed down from Nicolò Amati, suggest a connection. The homage to Guarneri’s model, arching and f-hole pattern is also evident in this period.

Around 1770 Balestrieri’s style undergoes a subtle yet significant change and takes on some of the characteristics of Stradivari’s late work – a squarer approach to the form, a flatness of arch and a preference for locally grown maple. Interestingly, Balestrieri’s contemporary G.B. Guadagnini was also adopting some Stradivarian features in the mid-1770s, under the influence of Count Cozio di Salabue in Turin. Cozio would almost certainly have made contact with Balestrieri when he enquired in 1776 about violin makers in Mantua, so was Cozio possibly responsible for this change of direction in Balestrieri’s work? Or was it simply Stradivari’s growing fame and the consequent demands of musicians for instruments on the Stradivarian pattern?

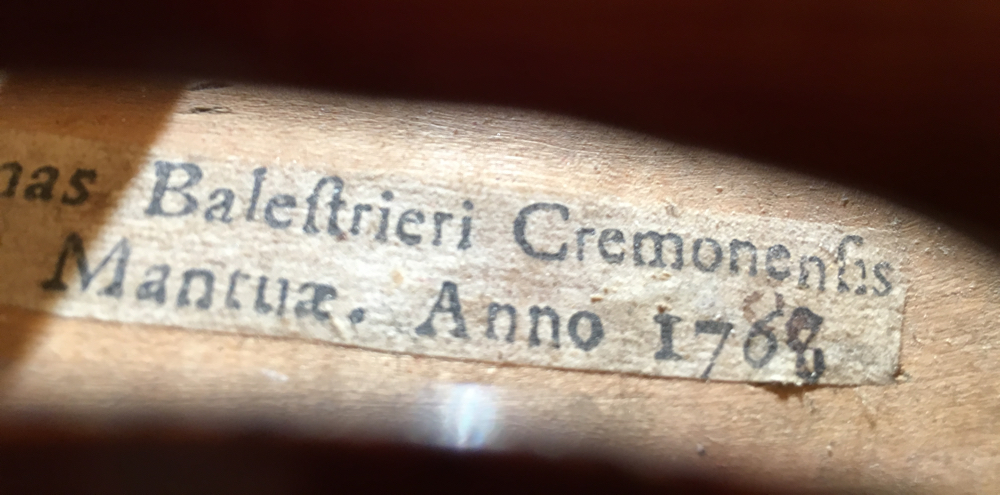

The label shows how Balestrieri amended the original printed 6 to an 8

The 1788 violin featured here is typical of Balestrieri’s late work, and one of its most fascinating aspects is the original label dated 1788. It appears that Balestrieri ordered too many labels in the early 1760s and made the mistake of having the first three digits printed (176). He continued to use these labels through the 1770s, 80s and 90s, amending them each time to suit the new decade. In the 1770s he often obliterated the 6, leaving a space instead; in the 1780s he added a loop to the upper stroke of the 6 to form an 8; and in the 90s the upper stroke was deleted and a lower stroke added.

This violin was in the private collection of the Parisian dealer and expert Albert Caressa in the early 20th century. It passed through the hands of Emile Français and William Moennig before appearing at auction at Sotheby’s in 1997. It has been in the hands of various European collectors ever since.

With grateful thanks to Philip Kass for his assistance with Balestrieri’s biographical information.