When I started working in Bologna in the 1970s, information about the Tononi family in the various books of the trade was imprecise and controversial. I already knew about the life and work of Laux Mahler, the celebrated lute maker from Füssen, who established himself in Bologna in the early 16th century, and I was curious about those makers who were subsequently involved in the construction of violins in the city. But the publications to which I had access reported obvious misinformation. In particular I remember the encyclopedia Alte Meistergeigen, published in Switzerland in 1978, which included the Tononis in the volume of the Venetian School, while the Bolognese school, among others, was totally missing.

I decided then to make a detailed publication on the Bolognese school one of the missions of my career. At the same time, by a fortunate chance, I met Sandro Pasqual, whose diploma dissertation Il Liuto e il Liutaio nella Società Emiliana in Età Moderna – Il Caso Bolognese immediately captured my attention, and this was the beginning of a long-term and fruitful collaboration. His daily visits to the Bologna State Archive were a vital resource for our task.

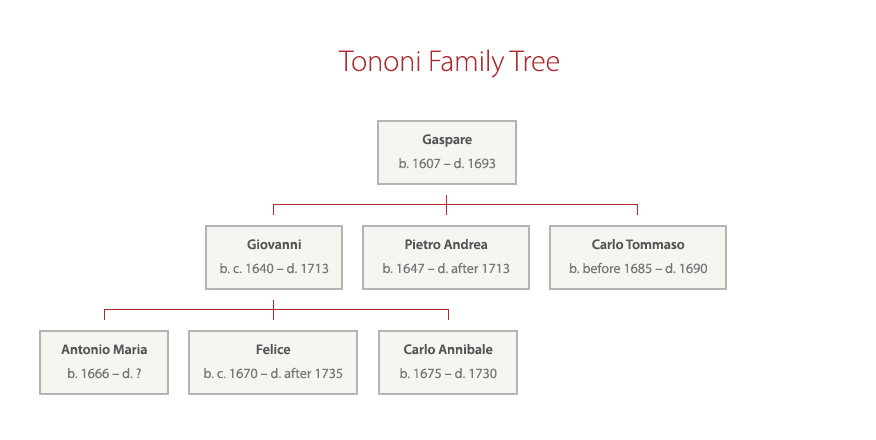

Pasqual discovered that the Tononi family had roots in Imola, very close to Bologna. The progenitor of the dynasty was Gaspare, recorded as ‘scatolaro’ (a case or crate maker), the father of Giovanni, Pietro Andrea and Carlo Tommaso (or ‘Tomaso’, as he is recorded in some papers). There was a close link between the profession of ‘scatolaro’ and that of the ‘liutaro’ or ‘violinaro’; we have other examples of case makers in Italy who ended up building instruments such as violins or lutes. Carlo Tommaso and Pietro Andrea are also recorded as ‘scatolari’, but Giovanni in 1688 had already established himself as ‘gitarraro’, a general term used in this context for a maker of bowed or plucked instruments.

The Tononis’ presence as craftsmen in the city of Bologna from the late 17th century is well documented. The brothers Giovanni and Pietro Andrea are traditionally reported as violin makers, but the former is the one whose existence had never been questioned, perhaps because he was linked to the more famous Carlo Annibale (until quite recently there was confusion about their exact relationship), or because a good number of genuine instruments from him had already been identified at that time. It is possible that Pietro Andrea made some instruments by himself or while helping his brother, but the records suggest that he didn’t put much effort into this, especially after the beginning of the 18th century, when he inherited wealth through his fortunate second marriage. Certainly instruments by him bearing his original label are unknown today.

Giovanni was therefore the first member of the family who appears to have had a stable violin making workshop. Various notarial papers indicate that by 1690 his instruments already had a good reputation, and two later documents support this. Three years before Giovanni’s death a violin belonging to Count Carlo Pepoli was stolen from the Tononi shop; the police report indicates this instrument as ‘valuable’ and the owner claimed a reimbursement value as high as 40 lire. The second document is an inventory from the shop of the Tononi’s colleague Andrea Fancelli around 1700, in which a cello made by Giovanni Tononi is given the highest price listed.

Giovanni was the first member of the family who appears to have had a stable violin making workshop. Various papers indicate that by 1690 his instruments already had a good reputation

In the 1680s Giovanni Tononi’s workshop was in Corte Galluzzi, almost exactly where 200 years later Giuseppe Fiorini was located for a few years when he left his father Raffaele. By 1697 his premises were in the very center of the city, in via San Mamolo (today via D’Azeglio) close to Piazza Maggiore, where almost 200 years before the famous lute makers had their workshops. For many centuries before the construction of the Teatro Comunale this was the lively cultural centre of Bologna. Great events such as the Festa della Porchetta, dating from medieval times, were held annually in Piazza Maggiore and quite often involved many professional musicians. Giovanni also benefited from the creation of the Accademia Filarmonica by Count Vincenzo Maria Carrati in 1666, a new institution that promoted musical performances in Bologna and in turn stimulated the art of making fine musical instruments.

Giovanni’s shop was run with the help of his sons, Carlo Annibale and Felice. Some experts – including Stefano Scarampella – have reported seeing labels of an Antonio Tononi, and we can speculate that the workshop may also have included Carlo and Felice’s eldest brother Antonio Maria, although there is no other evidence to suggest that he was a violin maker. When Giovanni died in the summer of 1713 he left his workshop to Carlo Annibale, assisted by Felice. Carlo Annibale took the main responsibility for the shop and continued to produce high-quality instruments, but major changes were soon to take place.

One cello survives with an original Giovanni Battista Tononi label dated 1740. Photos: courtesy Smithsonian, National Museum of American History

More photosAt the end of 1717 Carlo Annibale moved to Venice, where he remained until his death in 1730. He moved apparently for personal reasons, mainly to escape debts, but at that time the lagoon city also offered good opportunities for a luthier. The young Pietro Guarneri moved from Cremona in the same year and Matteo Sellas was already well established there and in need of experienced workers. After Carlo happened to take over the activity of Francesco Gobetti around 1722–23 he was able to work on his own, but he probably continued selling his instruments through the Sellas shop. In Venice Carlo Annibale was exposed to the Cremonese violin culture and this benefited his reputation, in comparison with all the other members of the family. However, he still referred to himself as ‘Bolognese’ in his labels even at the end of his career.

Meanwhile Felice had moved to Modena, perhaps for family reasons, and was living there at the time of Carlo Annibale’s death. Felice received all his tools and shop contents, as stated in Carlo Annibale’s last will of April 1730, but if we rule out all the uncertain Tononi labels, the family was no longer active in violin making after this date. The exception is a single intriguing example of a cello still in its original Baroque set-up, now in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution, which bears an unquestionable label: ‘Joannes Baptista de Tononis fecit Bononiae 1740.’ Until now we have found no evidence of a Giovanni Battista in Bologna in this period, so this instrument remains a puzzle. It could be that other instruments bearing a label with this name were relabeled at a later stage because Giovanni Battista wasn’t found in violin literature, or perhaps he was a descendant of the family but with a very limited output.

If we rule out all the uncertain Tononi labels, the family was no longer active in violin making after 1730

To summarize our knowledge of the remarkable Tononi family of violin makers, the most active members appear to have been Carlo Annibale for at least 35 years (c. 1695–1730, of which about 18 were in the family workshop and 17 by himself), his father Giovanni for about 27 years (c. 1686–c. 1713), very likely assisted for most of this time by two or three of his sons. The other two members documented as makers, Carlo’s brother Felice and his uncle Pietro Andrea, might have had a regular apprenticeship too, but no instruments with their original labels are known to survive. The same applies to Antonio Maria. It is plausible that the workshop in the Bolognese period needed income from repairs and sales of other instruments to remain open, so the work of these members of the family might have been subordinate to the main activity of violin making.

Data from the Bologna State Archive, research by Sandro Pasqual

Carlo Annibale Tononi instruments

Some instruments survive today with original Carlo Annibale Tononi labels or certificates. The varied output of the Tononi family reflects the time in which they were living: the form of the violin was still undergoing development and perhaps for this reason we find a variety of patterns in their instruments. Carlo Annibale was more aware than his father of the innovations coming from other Italian cities, especially Cremona, and his style is generally more mature.

Certainly after settling in Venice, Carlo Annibale became aware of a more personal approach to his craft. A violin made in the final years of his life has a curious label: ‘Carlo Tononi Bolognese fece l’A[nno] 1729 e del 1728 disenij di far prove n’egli istrumenti e principiai a far originali’, which can be translated as: ‘Carlo Tononi from Bologna, made in 1729; by 1728 I ceased to experiment with the instruments and started with my own style.’ If this is true, it is a pity that he had such a short time left to live!

Roberto Regazzi is co-author with Sandro Pasqual of ‘Lutherie in Bologna: Roots & Success’.