Two weeks ago Jason Price documented the life of the Chilean collector Antonio Antoncich. This week and next, he profiles two of the extraordinary instruments in his collection, the ‘Naryshkin, Antoncich’ Bergonzi and the ‘Primrose, Lord Harrington’ Guarneri viola both recently sold by Tarisio Private Sale.

New research has identified the first known owner of this Bergonzi violin as Georgiy Dmitrievich Naryshkin. Born in Saint Petersburg in 1848, Naryshkin was descended from a line of nobility which was linked to the Tsar of Russia through the marriage of Natalia Kirillovna Narychkina to Tsar Alexis I in 1671. Naryshkin’s family had several musical connections. His father, Dimitri Ivanovitch Naryshkin (1812-1866), was a close friend of the composer Mikhail Glinka[1] and his grandmother, Varvara Ivanova Ladomirskaya (1776-1840), was the illegitimate daughter of Ivan Rimsky-Korsakov[2] an amateur violinist, courtier in the orbit of Catherine the Great and ancestor of the composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov.[3]

Georgiy Dmitriev Naryshkin in c. 1890.

Georgiy Dmitrievich had moved to London by 1889 and married Elizabeth Harriet Knight the following year.[4] He inherited two estates in Lithuania upon the death of his brother in 1894 and divided his time between Lithuania and London. It’s not currently known where or when Naryshkin acquired this Bergonzi, but he sold it to W. E. Hill & Sons before 1921.[5] He died three years later and is buried in the Brookwood cemetery in Surrey.[6]

This Bergonzi was the first great instrument of Antoncich’s collection and it was such a momentous purchase that he proposed naming his newborn daughter Bergonza.

In March 1922 the Chilean collector Antonio Antoncich purchased the violin from the Hills, and it arrived in Valparaíso in May 1922.[7] This Bergonzi was the first great instrument of Antoncich’s collection and it was such a momentous purchase that he proposed naming his newborn daughter Bergonza. Fortunately, his wife and older children rejected this suggestion. Antoncich owned the violin for more than three decades — the longest that he held onto any of his instruments. Around 1954 the violin was acquired by Francisco Moreno Marco, a fellow Chilean, shortly before Antoncich’s death in 1955.

Antoncich with one of his sons in his home in Valparaíso

In 1975, the violin was acquired by Wilhelm Melcher, the German violinist and founder of the Melos Quartet; it was to become his main concert violin for the rest of his career. After Melcher’s death in 2005, the violin remained in his family for another decade. In 2010, it was exhibited as part of the Bergonzi exhibition at the Museo Civico ‘Ala Ponzone’ in Cremona and was sold in 2014 by Tarisio Private Sales to a distinguished musician and collector.

The Melos Quartet. Wilhelm Melcher is second from the left.

This fine violin dates to Carlo Bergonzi’s last period when he was working in close collaboration with his son Michele Angelo. Its features are striking and the tonewood is of exceptional quality. Handsome, broad flame ascends from the center joint at a steep angle, giving the back a dramatic presence. This same wide-flamed maple was used often during the best years of Bergonzi’s production but typically in the configuration of a one-piece back and typically with flame descending from treble to bass.[8] There are comparatively few Bergonzi violins with two-piece backs, and almost none of those feature this highly flamed wood. The original wing in the lower treble bout suggests that the piece of wood was not quite wide enough to cover half the back and could have been a remnant from earlier days.

Its features are striking and the tonewood is of exceptional quality. Handsome, broad flame ascends from the center joint at a steep angle, giving the back a dramatic presence.

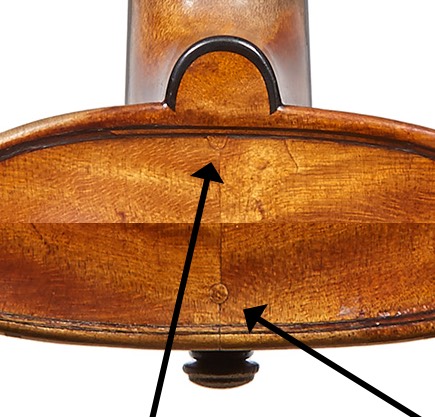

The model of this violin is slightly undersized. Most Bergonzi violins have a back length between 35.1 and 35.3 cm but the ‘Naryshkin, Antoncich’ measures just 34.7 cm. The 1744 ‘Eddy Brown’ Bergonzi is a close match at 34.9 cm, but questions remain: was this smaller model made upon request, or was it a spontaneous variation? A clue to answer this question may come from examining the locating pins at the upper and lower edges of the back. Bergonzi’s locating pins were usually not round but faceted and slightly tapered and their position and size varied over the course of his career. In some examples the pins are set adjacent to the purfling and in others the pins are set inside – towards the center of the instrument – by as much as 3 mm. In most cases, the amount of inset in the upper and lower bouts is the same but in the ‘Naryshkin, Antoncich’ the placement of the upper locating pin is significantly closer to the purfling than the lower pin. This is likewise the case with the slightly undersized 1744 ‘Eddy Brown’. This would seem to indicate that the back outline of this violin (and consequently the purfling position) was finalized after the pin position was set, perhaps as a special request or a deliberate variation.[9]

There are few Bergonzi violins with two-piece backs, and almost none of those feature this highly flamed wood

Usually the locating pins are set the same distance inside the purfling. On this violin, the upper pin (now capped) is much closer to the purfling, perhaps offering some clue as to the slightly undersized back length.

We see the hand of Michele Angelo in this violin in the short-ish corners, the rounded and slightly ropey edge and, most evidently, in the cut of the sound-holes and the carving of the head. Although elegant and well formed, the sound-holes of this violin lack the discipline and presence of Carlo’s work from the prior decade. The upper and lower sound-hole wings of this violin are narrow and slightly pinched whereas Bergonzi wings from the mid-30s are wide and rectangular.

The sound holes of the c. 1732-34 ‘Earl of Falmouth’ (left) and the ‘Naryshkin, Antoncich’. The position is more or less the same but the wings are dramatically different.

This new model of soundhole, which appeared around 1740 is seen in the 1742-44 ‘Sandler’, the 1743-47 ‘Meinertzhagen’, the 1744 ‘Eddy Brown, the 1743-47 ‘Baron Eichthal, Baron Heath’ and others. The position of the sound-hole and the location of the original drill holes are more or less the same as they were on the violins from the 1730s, but the layout of the upper and lower wings, and the stems connecting them, are different. The purfling on the ‘Naryshkin, Antoncich’ violin is also wider and less precise, and the corners end in blunt, unrefined miters.

(Left to right) The 1742-44 ‘Sandler’, the 1743-47 ‘Naryshkin, Antoncich’ and the 1743-47 ‘Meinertzhagen’.

It is the head of this violin which deviates the most from the earlier work of Carlo and reveals the hand of his son. The unfigured wood is a stark contrast to the dramatically flamed maple of the back and ribs, and the model and workmanship is imprecise and hastily finished. The side views only vaguely resemble the Bergonzi scrolls of the mid 1930s, but interestingly, the front view retains the characteristic Bergonzi splay of the second turn of the volute.

It is the head of this violin which deviates the most from the earlier work of Carlo and reveals the hand of his son.

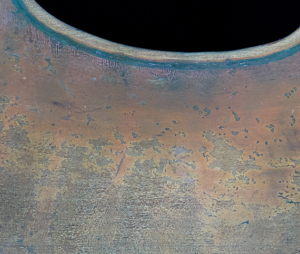

Perhaps the finest aspect of this violin is its exceptional ruby-red varnish. It possesses the same luster, texture and depth of color as the best quality Bergonzi violins such as the ‘Knoop’, the ‘Pennington’ and the ‘Reiffenberg, Brooks’.

The exceptional ruby-red varnish is of the same luster, texture and depth of color as the best Bergonzi violins of the mid 1730s.

An image of the back under UV light shows the fine structure of the varnish and the delicate feathering of its layers.

Tarisio has recently taken consignment of an exceptional Carlo Bergonzi violin for Private Sale. With serious inquiries, please contact Carlos Tome at ctome@tarisio.com.

Notes

[1] S.M. Zagostin, ‘Historical Report,’ Historical and Literary Journal, 1900.

[2] I.M. Dolgorukov cited in ‘The temple of my heart, Literary Memories’, Russian Academy of Sciences, 1997.

[3] Louise-Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, Souvenirs de Madame Louise-Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, de l’Académie Royale de Paris, de Rouen, de Saint-Luc de Rome et d’Arcadie, de Parme et de Bologne, de Saint-Pétersbourg, de Berlin, de Genève et Avignon, Book I (Paris, Librairie de H. Fournier, 1834): https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k208330j/f8.image#.

[4] The National Archives, England & Wales, Non-Conformist and Non-Parochial Registers, 1567-1936. RG8: Piece 0281: 1835-1895.

[5] W. E. Hill & Sons, Business records (unpublished).

[6] “Georgiy Dmitrievich Narishkin,” Geni, accessed on April 22, 2021, https://www.geni.com/people/Georgiy-Dmitrievich-Narishkin/6000000020369925300.

[7] José Pérez de Arce, “Don Antonio Antoncich, musical philanthropist. Valparaíso c. 1920,” Resonances, no. 23 (November 2008), 15.

[8] Interestingly, of the 37 Bergonzi violins with a one-piece quarter-sawn back, nearly 80% (29) have flame descending from treble to bass.

[9] Typically, in the Cremonese system, the outlines of the top and back are more or less finalized while the ribs are still on the mould. In practice there is the possibility for micro-adjustments to the outline by freeing the ribs from the mould prematurely but a deviation of 5 mm would almost certainly require a new mould or a very unorthodox improvisation. In John Becker’s exceptional technical analysis of Bergonzi’s working methods in the catalog to the 2010 Bergonzi exhibition, he points out that there are often facets on the top (visible) edge of the locating pins, indicating that the pins were inserted and trimmed after the arching and fluting was finalized. If the back were positioned on the mould normally and then later the intended back length were shortened, the pin position would be asymmetrical, as it is on the ‘Naryshkin, Antoncich’.