The Musée de la musique’s collection shares its origins with the Conservatoire National de Musique, founded during the French Revolution. The musée itself opened to the public only a century and a half ago, in November 1864, exhibiting a collection of instruments that the French state had purchased from the composer, violinist and collector Louis Clapisson. At the time the conservatoire was located on rue Bergère in the 9th arrondissement. Two exhibition rooms in part of the conservatoire’s library were then opened to visitors, but on Sunday afternoons only!

In 1911 the conservatoire moved to another building located on rue de Madrid (8th arrondissement), which soon became too small. The project of a Cité de la musique, located on the southern part of the Parc de la Villette (19th arrondissement) emerged in the 1980s. The collections of the Musée du Conservatoire were transferred to the new Musée de la musique, which opened in 1997 as part of the Cité de la musique.

A gallery at the Musée de la musique, which owns over 7,000 instruments, bows and other artefacts. Photo: Nicolas Borel

Several important private collections of instruments have been added to the musée’s collection, including those of Paul Cesbron in 1934 and Geneviève Thibault de Chambure (a former musical instruments curator at the conservatoire) in 1979 and 1980. Other donors have included the violinists Pablo Sarasate and Teresa Tua, and violin dealer Jacques Français.

Among the instruments from Clapisson’s collection is the only surviving pochette from Stradivari’s workshop. It is said to have been brought to France by Luigi Tarisio, who likely sold it to the Lyonnese maker Pierre Silvestre, from whom Clapisson bought it.

This relatively large instrument ‘en forme de violon’ (length of back 320 mm) is quite similar in shape and dimensions to a paper pattern from Stradivari’s workshop, conserved in the Museo del Violino in Cremona. The pochette was entirely restored by Emile Français in 1942–1944.

The ‘Davidoff’ Stradivari, which was played by the 12-year-old Kreisler in 1887. Photo: J.-P. Echard, Cité de la musique

The ‘Davidoff’ violin, dated 1708, is the first of the musée’s five Stradivari violins to have entered the collection, in 1887. Its previous owner was a Russian general, Vladimir Alexandrovitch Davidoff (1816–1886, no relation to the cellist Karl Davidoff, after whom the 1712 Stradivari cello is named). An amateur violinist, he was the son of the French noblewoman Aglaë de Gramont, who fled Versailles to Eastern Europe in the turmoil of the French Revolution. Davidoff visited Paris (and died there) in the 1880s: he had his violin examined by Charles Eugène Gand in 1880, visited the conservatoire and the musée, and subsequently bequeathed the instrument to the institution. The violin was played at the conservatoire’s 1887 prize ceremony, by the first prize winner of that year… a certain Fritz Kreisler, who was then 12 years old!

The instrument is well preserved: in particular, the one-piece slab-cut maple back and the headstock still reflect the excellent craftsmanship of the Stradivari workshop during this period. It was recently restored to playing condition at the musée’s Conservation Laboratory, and a recording was made by David Grimal at the musée.

Another Stradivari violin in the collection is the beautifully preserved ‘Provigny’ of 1716, bequeathed – along with other important stringed instruments and bows – in 1909 by Madame de Provigny, the daughter of Louis Edouard Besson. This eminent French businessman and politician (1783–1865) was a keen music enthusiast who owned violins, violas and a cello, and attended many of Pierre Baillot’s famous chamber music sessions in the 1820s and 1830s. He was a client of Charles François Gand, the first successor to Nicolas Lupot.

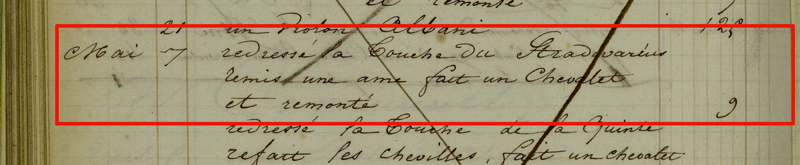

The musée holds extensive archives of this workshop covering 120 years and recently Gand’s work on the ‘Provigny’ has been found recorded in account books as early as May 1827, when its fingerboard was straightened and a new soundpost and bridge were added.

The earliest mention of the ‘Provigny’ violin in an account book from the workshop of Charles François Gand 1816–1831

Three examples by Matteo Goffriller demonstrate some of the new designs created by Venetian makers around 1720 for the lower-register instruments: a large cello (length of back 77 cm) with its head and varnish particularly well preserved; a small double bass (length of back 110.4 cm) with a head of different origin, replaced at the same time as the neck; and a larger double bass with poplar ribs and a viol-like flat back that is bent as well as arched (length of back 115 cm). At this time the technology of wound strings began to allow shorter string lengths for cellos and double basses, increasing the possibility of virtuosity.

A Matteo Goffriller cello and two basses demonstrate his development of the lower register instruments. Photos: J.M. Anglès

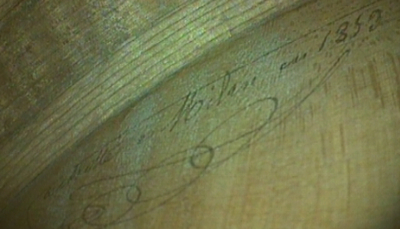

Vuillaume’s inscription and paraph inside the ‘Alard’. Photo: A. Houssay & J.-P. Echard, Cité de la musique

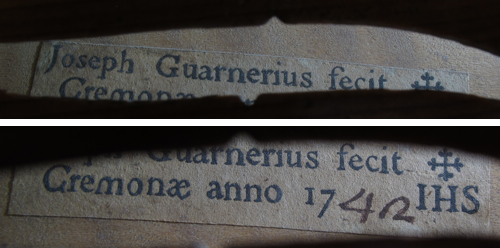

The musée’s 1742 ‘Alard’ violin by Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ is named after Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume’s son-in-law Jean-Delphin Alard, who succeeded Baillot as a teacher at the Conservatoire de Paris. Vuillaume bought this violin before Tarisio’s death in 1854, when it is said that the dealer traveled to Milan to fetch what was left in the old man’s room. Using a fiberscope we discovered Vuillaume’s paraph inside the violin with the inscription: ‘achetté [sic] à Milan en 1853.’

Label of the ‘Alard’. Photos: A. Houssay & J.-P. Echard, Cité de la musique

In 1823 a brand new violin by Nicolas Lupot was given as first prize to a student of the Ecole Royale de Musique, as the painted ribs testify. A violin made by Nicolas’s father François Lupot in Orléans in 1772, in pristine classical original condition, was bought at a sale following Vuillaume’s death in 1880. In 1996 the musée acquired another violin by Lupot made in 1803 from the Français family’s collection, bearing the label ‘Nicolas Lupot luthier rue de / Grammont à Paris l’an 1803’. One can admire the mastery of both father and son, who clearly appreciated the old masters’ work but were able to create their own models for fine instruments.

In 2000 an extraordinary double bass bow by François-Xavier Tourte, with a pernambuco stick, original silver-plated ebony frog and silver head facing attached with four pins, entered the musée collection. It is featured in ‘L’Archet’ by Millant, Raffin, Le Canu and Gaudfroy. The D ring is engraved: ‘Lambert Massart / à son frère Victor / 1842.’ The Massart family included several virtuosos: Lambert taught the violin in Paris, while Victor taught the double bass in Brussels. The bow had been made some years earlier, according to a small label by the hand of the maker, inserted in the mortise: ‘cette archet a été fait [sic] / par tourte agé de 77 / ans. en l’année 1824.’

Pierre Hel ‘Grappelli’ violin. Photo: J.M. Anglès

The ‘Grappelli’ violin by Pierre Hel (Lille, 1924) was given to the musée by the great jazz violinist Stéphane Grappelli. Joseph Hel, who was trained and worked in Mirecourt in the 1860s, was encouraged by Vuillaume to establish his workshop in Lille. His son Pierre also learned the craft in Mirecourt, and he followed the French style, adopting his father’s red varnish and winning a first prize in the Paris 1900 International Exhibition: this violin is also in the musée’s collection, labeled ‘Joseph Hel / Luthier à Lille 1901’ and stamped ‘Grand Prix’. After his father’s death in 1902 Pierre took over as head of the wealthy shop with its international connections, and after World War I his violins became popular with soloists: George Enesco, Eugène Ysaÿe and Jacques Thibaud praised his work, as well as Michel Warlop, the 1930s swing virtuoso. The 1924 violin has a paler orange varnish and more personal, curly f-holes than the 1901 example.

The ongoing centenary commemoration of World War I has created the opportunity to present an instrument made for the cellist Maurice Maréchal (1892–1964) while he was on the Western Front in the French army, soon after graduating from the conservatoire. The cello was made in 1915 by Neyen and Plicque, two woodworkers mobilized in the same regiment with Maréchal. They used fir planks from ammunition crates to make the soundbox, and the oak piece for the neck and headstock may have come from a door frame. The flat soundboard and back are nailed to the ribs. They originally may have been slightly bent by the soundpost (now missing), given the shape of the bridge’s feet.

Maurice Maréchal and his ‘Poilu’. Photo: Musée collection

Maréchal and his ‘Poilu’ – as he nicknamed his instrument – were frequently invited to perform at the division field headquarters, and the marshals Joffre and Pétain, as well as the generals Foch, Mangin and Gouraud all signed the soundboard. This unique instrument is now an invaluable and moving testimony to the role of musical performances and instrument making in the traumatizing, violent and absurd context of World War I. The instrument is currently on view in the exhibition ‘La musique malgré tout’ at the Musée de la lutherie et de l’archèterie françaises in Mirecourt.

We have highlighted here just a few of the stringed instruments and bows in the collection of the Musée de la musique, of which around 100 bowed string instruments and around 60 bows are displayed in the galleries. The full collection now numbers more than 7,000 instruments, artworks, instrument-making tools and archival materials, and is continuously growing thanks to purchases, gifts and bequests.

Jean-Philippe Echard is curator of the collection of bowed string instruments and bows at the Musée de la musique. Anne Houssay is conservation specialist at the Laboratory of the Musée de la musique.

Find out more

The collection of Louis Edouard Besson: ‘Un amateur de musique du XIXe siècle: Louis Edouard Besson et ses violons’, by Echard J.P. and Malecki M., Musiques•Images•Instruments, vol. 15, 2015, shortly to be published

World War I viewed from the Musée de la musique collections