In Part 1 we looked at the involvement of Antonio Stradivari’s sons in the workshop during his lifetime. By the time of his death in 1737 it is hard to know with any accuracy what was going on in the Casa Stradivari, but the work we can attribute to the sons after this date shows comparatively strong divergencies.

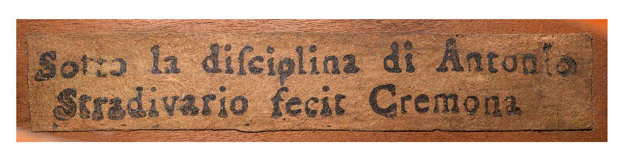

Only a handful of instruments are reliably attributed to Francesco alone. The best-known example is the ‘Salabue’ of 1742, which supplies us with one of the only two authentic labels known: ‘Franciscus Stradivarius Cremonensis / Filius Antonii faciebat Anno 1742’ (although it is no longer in the instrument). Notably it omits the A+S stamp that occurs on Antonio’s labels. Another label states ‘Sotto la Disciplina d’Antonio / Stradivari F. in Cremona 1737’ although here the ‘F’ stands for ‘faciebat’ rather than ‘Francesco’. This is of course the year of his father’s death, and the phrase ‘sotto la disciplina’, although it appears in a few other instruments, may here be a particular sign of his respect.

The 1742 ‘Salabue’ is the best-known instrument by Francesco. Photos: Peter Biddulph Ltd

More photosCount Cozio di Salabue tells us that when he bought the contents of the Casa Stradivari from the last surviving son, Paolo, in 1775, he obtained two masterpieces by Francesco. One was the ‘Salabue’, the other is now lost, or may be one of the few other violins fully attributed to Francesco, the 1734 ‘Le Besque’ or ‘Oliviera’. Stylistically they are quite varied, but one feature linking the ‘Salabue’, ‘Le Besque’ and 1734 ‘Petersen’ is the slender and strongly curved lower wings of the ‘f’s. There is also a curious feature to the eye of the scroll, which has a particularly heavy tail and a wide last turn, recalling the style of Giuseppe ‘filius Andreae’ Guarneri.

There are far more surviving Omobono instruments – between 15 and 20. This comes as a surprise after the role that most authorities have generally ascribed to him as setter-up and adjuster, or roving sales representative. Intriguingly some of these are supposed to date from as early as 1699, several are from 1725 and beyond, but most are rightly or wrongly attributed to the year 1740. Possibly only three bear reliable labels in Omobono’s name; two have manuscript labels stating ‘Omobonus Stradivarius Filius Antonij / Cremone Fecit Anno 1740: oTs’. Even in the printed labels of the sons, the typeface is noticeably poorer than that of the well-known Antonio labels.

The original label of the ‘Blagrove’ by Omobono

After the 1700 ‘Blagrove’, the next fully verifiable independent work of Omobono with an original label is the ‘Powell’ from 1724 and has the form ‘sotto la disciplina d’Antonio’. This has interesting implications. Why did he use this label if he was still a part of the family workshop? Why did Antonio even allow him to use his own name? This would have been impossible in any other workshop, least of all the patently authoritarian Casa Stradivari. Two possible answers are that Omobono was moonlighting away from home, and we know he had left the family workshop on at least one previous occasion, or that the work was of an inferior nature for which Antonio was reluctant to take full responsibility. Yet most of the other instruments ascribed to Omobono bear the usual Antonio Stradivari label, complete with the ‘A+S’ imprint. Made between 1724 and 1737, while Antonio was alive, these eccentric instruments were mostly made from very plain materials, and it’s hard to imagine that they could have received Antonio’s approval. Those made after Antonio’s death, from 1737 until Omobono’s own death in 1742, are in much the same style, although a group consisting of a c. 1727 violin owned by the Royal Academy of Music and the c. 1740 ‘Freiche’ and ‘Quid’ are of a higher quality, with finely figured oppio maple.

This c. 1727 Omobono violin features a typical finely figured oppio maple. Photo: courtesy Royal Academy of Music

More photosIn general Omobono’s instruments are not firmly delineated. The edges are slender and flat, the ends of the corners irregular. He seems to have had difficulty regulating the outline itself, with the C-bouts most often distorted and asymmetrical. The scrolls are rather skinny, with a smaller chamfer, a clumsy last turn into the eye and an extended throat. The soundholes are narrow, with crude fluting and constricted upper points and little care taken of the angle of the wings. Generally quite broad, the wings can be long or short, but the terminal angle is quite variable. In truth much of his workmanship suggests a maker not fully in control; most noticeable is the general poverty of his materials, including plain maple and even poplar and beech, not seen since the earliest years of Antonio’s career. Perhaps Antonio was protective of his own hand-picked pieces, but it is surprising that some of these meagre cuts were even in stock in the Casa Stradivari.

By comparison, Francesco’s late work is far more distinguished. The edge is well handled, the work overall is confident and bold, and the heads are barely distinguishable from those of his father, although they have a heavier quality, with broad chamfers and are a little undercut. The soundholes seem to have an exaggeratedly curved stem and the lower wings are narrow and more curved in shape with a consistently steep cut-off angle. Some of them fascinatingly prefigure the later work of Guarneri ‘del Gesù’: the soundhole of one 1732 Francesco violin might easily come from a 1743 Guarneri.

The f-holes of a 1732 violin by Francesco fascinatingly prefigure the later work of Guarneri ‘del Gesù’

What is most obvious in the work of both sons is the startlingly poor purfling. On the ‘Salabue’ the points struggle to meet in the corners. On another late example attributed to Omobono, the purfling is a single strand of dyed pearwood, as is also surprisingly found in the ‘Romberg’ cello of 1711.

To try and untangle the knot of ‘who-did-what’ in the period before 1737 we can look at the Stradivari instruments in definitive stages. Francesco probably joined the workshop around 1684, but he is hardly likely to have been a major influence until his mid-20s, at least ten years later, and this coincides with the remarkable changes that mark the beginning of the golden period. It would be extremely rash to attribute all this to Francesco, but we can certainly imagine a workshop that had been established for over 40 years benefiting from a new charge of energy, enthusiasm and imagination.

During the golden period we can also discern at least three variations in the cutting of the soundholes. In the violins we can see the widely cut, steeply sloping soundholes of the ‘Soil’ and ‘Messiah’ for example, contrasted with the slender, more upright forms of the ‘Tyrell’, ‘Reynier’, ‘Woolhouse’, ‘Leveque’ or ‘Lady Blunt’, which become more dominant in the 1720s. The difference in the width of the stem of the ‘f’ seems to be due to a slightly different angle at which the edges are cut, the wider ‘f’ resulting from a more vertical knife stroke, while the narrower form comes from a slightly inward angled knife cut. Then there is the form which seems particularly dominant in the violas and cellos from 1696 up until the end of the Stradivari workshop, in which the upper wing is cut quite short, with a flatter angle. Does this mean a different hand (Francesco’s?) was responsible for all these? It certainly makes sense to imagine that the cellos in particular were a physical challenge to the older Stradivari, by then in his 80s, and might have been passed to the younger workmen.

Different variations can be seen in the cutting of the f-holes during the golden period, as the ‘Soil’ (left) and ‘Woolhouse’ (center) violins demonstrate, while later violas and cellos such as the 1732 ‘Josefowitz’ (right) show another form again – possibly the work of Francesco

It certainly seems clear that Antonio worked very closely with Francesco and grew to trust and rely on him to an increasing degree throughout his life. Innovations might have come from both or either men, but the decisive role was Antonio’s, and so close were they that it matters little whose hand held the gouge. Omobono’s case is different. His labeled work is clearly of a different order to that of either Antonio or Francesco. There is little evidence of trust between father and son, and his use of his own label while his father was still alive suggests a distance between them.

In the catalog of Antonio Stradivari’s authentic labeled work there are several late instruments that show the sons’ work clearly, overwhelming the contribution of their father. The ‘Cassavetti’ viola of 1727 is within this group, with rather wayward soundholes, the wings unfluted. Very similar is the ‘Habeneck’ violin of c. 1734, which shows precisely the same soundhole disposition, with the treble side cocked higher than the bass. The 1732 ‘Stuart’ cello, 1728 ‘Wilhelmj’ and 1732 ‘Baillot’ also seem to have the sons’ clear imprint, and the 1729 ‘Defauw’ has Omobono’s characteristic soundholes. In fact it is easier to enumerate the undeniable Antonios from this late period, which would include the 1733 ‘Kreisler’, the 1734 ‘Lord Amherst’ and ‘Lord Norton’, and the celebrated ‘Chant du Cygne’ from his last year of 1737.

A mystery remains in the handful of violins attributed to both brothers from as early as 1698. These are ‘long pattern’ instruments, traditionally ascribed to the period 1690–1700, but clearly of the kind of workmanship associated with the brothers’ very late work. A surprising late ‘long pattern’ violin is the ‘Petersen’ of 1734. These were probably instruments started by Antonio but abandoned after the relative failure of the design and later revived by the sons. The Casa Stradivari in 1737 seems to have been full of complete and half-finished instruments from various stages in the master’s career. According to Count Cozio, there were ninety one violins, two cellos and several violas. It seems beyond doubt that the brothers and Carlo Bergonzi were fully engaged in finishing these last instruments, and the ‘long pattern’ violins of c. 1740 are the result.

Among this vast stock there must have been work rejected by Antonio as flawed or of inferior quality. Dendrochronology by John Topham shows a pattern of these late-period efforts attributed to the sons using wood more usually found in much earlier work, from 1718–1720. This was the material Francesco, Omobono and Bergonzi had to work with in their final years, after having worked in Antonio’s shadow all their lives. It was not the new generation of Stradivaris that Antonio must have hoped for. Omobono died only five years after his father in 1742, aged 63; Francesco followed him the next year, at the age of 72. The craft of violin making had changed irrevocably, partially due to Antonio’s success. Imitators and competitors had set up in business across Italy and beyond, and Cremona no longer had a monopoly. It took Paolo, the last son and heir of Antonio, the best part of 40 years to dispose of almost a hundred remaining Stradivari instruments, selling the last to Cozio in 1779.

It took Paolo, the last son of Antonio, the best part of 40 years to dispose of almost a hundred remaining Stradivari instruments

A great drama could be written about the Casa Stradivari. Antonio, the man with no known past or parentage, marries the widow of a successful citizen who mysteriously has ‘committed suicide with an arquebus’. With Francesca he buys property, has five children and becomes a perfectionist, authoritarian father, and the greatest violin maker of all time. Then Francesca dies and Stradivari swiftly marries the daughter of another wealthy Cremonese, prompting his sensitive son Omobono to walk away from the family home. With his new wife, a new family and new heirs, new rivalries in the workshop develop over the prodigiously gifted Giovanni Battista, who makes one masterpiece, and then dies. The old man takes his final revenge in a will that honours his obedient, loyal son and disinherits the spirited Omobono at a time when the family business is in crisis.

What we know and what we can speculate are very different things. What we can see in a single knife cut in a violin is very limited. But what we have in the legacy of the Casa Stradivari is without doubt one of the great assets and joys of western art, and that includes the contributions of Francesco, Omobono and Giovanni Battista.

John Dilworth is a maker, writer and expert. He has written extensively about fine instruments and their makers, and is a co-author of ‘The British Violin’, ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ and ‘The Voller Brothers’ among other books.