At first glance, the ‘San Lorenzo’ appears to be a typical fine example of Stradivari’s golden period. Its model is broad and graceful; its back is of two pieces of handsome quarter-cut maple; the ribs and scroll are crafted from similar wood; the spruce table is of fairly open and very even grain; the sound-holes are elegantly cut; and the translucent varnish is of a rich orange-brown color on a golden ground. Yet there is a detail that distinguishes it from all other Stradivari instruments that have survived today: the fascinating Latin inscription on its sides.

The faint remains of the original inscription on the treble rib: ‘Gloria et divitiae’. Photo: Jan Röhrmann

On the center treble rib of the violin are still visible traces of the words ‘Gloria et divitiae’, followed on the center bass rib by the words ‘in domo eius’. This inscription appears to be contemporary to the violin but why was it added? And what is the origin and the meaning of this phrase?

The rest of the inscription is on the bass rib: ‘in domo eius’. Photo: Jan Röhrmann

The words come from verse three of Psalm 111. [1] The complete Latin verse reads as follows: ‘Gloria et divitiae in domo eius, et justitia eius manet in saeculum saeculi’, which is translated as: ‘Wealth and riches shall be in his house and his righteousness endures for ever and ever’. Only the first part of the verse is depicted – perhaps because there was not enough space to reproduce the full text, or possibly due to a deliberate choice.

In Stradivari’s day this psalm was famous. Parts of it can be found in paintings, sculptures and music compositions from the 16th century onwards, and it was surely familiar to Stradivari. For example, he might well have heard the Moral and Spiritual Forest (c. 1640) by the Cremonese-born Claudio Monteverdi and he was probably also acquainted with the three Beatus vir that Antonio Vivaldi composed between 1713 and 1719. This psalm also remained popular after Stradivari’s time. Mozart (Vesperae Solennes de Dominica and Vesperae Solennes de Confessore) and Michael Haydn (Beatus vir) set the text to music, to name just a few.

If the provenance of the inscription is clear, let us turn to the reason for using it. Several experts have proposed different theories. At the beginning of the 20th century Arthur Hill suggested that the inscription ‘was ordered directly from Stradivari by one of the noble houses of Italy where it remained until it was purchased by Pichel.’ [2] The catalog from the 1937 Stradivari Bicentenary exhibition [3] erroneously asserts that Stradivari made the instrument for the Duke of San Lorenzo and painted the inscription as a dedication to him, a misconception shared by Ernest Doring. [4] More recently Duane Rosengard has linked the motto to the first known owner of the instrument, the violinist–composer Mauro D’Alay (1687–1757), also known as Maurino Dalay or Dallay. D’Alay got married in October 1717 and, according to Rosengard, ‘the violin was more than likely a wedding gift’ from ‘his father-in-law Giuseppe Venturini, a violinist who had served the Farnese dynasty in Parma for many years.’ [5]

This last hypothesis seems to fit. Nevertheless, the story appears to be more complicated than that. According to Count Cozio di Salabue, when Antonio Stradivari died in 1737 he left ninety-one violins, two cellos and several violas to his son Francesco, who sold some of them and in turn bequeathed what was left over to his brother Paolo in 1743. Later on Paolo, who was primarily a ‘cloth merchant or warehouseman’, [6] sold his father’s last instruments, forms, patterns, moulds and paper drawings from the workshop. Most of this material was bought by Count Cozio with the help of Giovanni Michele Anselmi. Anselmi was also a cloth merchant, who dealt in textiles as well as in musical instruments, and he was Cozio’s primary agent. Letters from Anselmi show that the count tried on several occasions to buy the ‘San Lorenzo’ but he never succeeded.

Letters from Anselmi show that Cozio tried on several occasions to buy the ‘San Lorenzo’ but he never succeeded

In one letter dated June 25, 1775, Paolo Stradivari explained to Anselmi that it was Francesco who had sold the instrument to D’Alay: ‘acquistò ancora quello del sig. Maurino Delaij, vendutolo anni prima da mio fratello Francesco.’ [7] So according to Paolo, it was D’Alay who purchased the violin, not his father-in-law, Venturini. Furthermore, the sale was apparently made by Francesco. It is well known that Antonio Stradivari used to run the family business personally. And while Francesco’s contributions to the making of Stradivari instruments are widely acknowledged, his involvement in the commercial side of the business during his father’s lifetime is unclear. So why does Paolo mention his brother and not his father? Is it possible that D’Alay bought the violin after Antonio’s death? Was Arthur Hill right in thinking the decoration on the sides of the violin reproduces the motto of a noble Italian family, who commissioned Stradivari with the work but for some reason didn’t collect it? This would also explain why the violin bears an original label dated 1718, although D’Alay got married the previous year. A further supposition could relate the purchase by D’Alay to the birth of his son Gaetano, which occurred in August 1718. We could probably come up with other theories that ‘fit’ the known facts, but at the moment there is no evidence to confirm any of them, as we have no documentary proof of exactly when D’Alay acquired the violin.

Dome of Santa Maria della Steccata in Parma, where the violin’s first known owner, the violinist–composer Mauro D’Alay, was active. It was also home to the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George

So far all we can confirm is that D’Alay was the first known owner of the ‘San Lorenzo’. He was a popular violinist and one of the foremost composers of his time. He was born in Parma, where he was active in the cathedral as well as in the Basilica of St Mary of the Steccata. When the Duchess of Parma, Elisabeth Farnese, married King Philip V of Spain in 1714, D’Alay moved to Spain with the queen’s entourage and remained there for some years at the service of the royal couple. He later traveled on several other occasions to Spain, where he spent a considerable time at the king’s court as First Violinist of his Chamber and amassed a notable collection of paintings. [8]

In 1754 D’Alay made a will and left everything he owned to the Constantinian Order, including his Stradivari violin

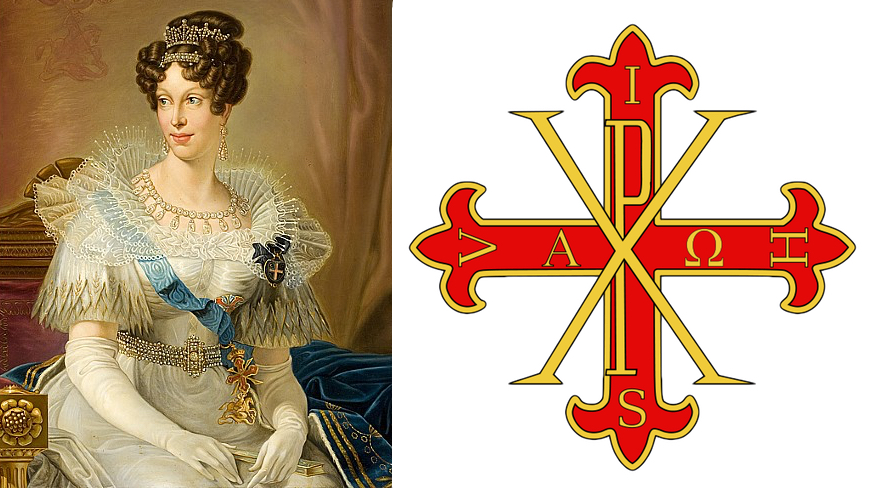

D’Alay also lived and worked in England, Germany and The Netherlands and, despite his marriage, is thought to have conducted a long-standing relationship with the celebrated Italian mezzo-soprano Faustina Bordoni. He returned to Italy for good only in 1747. Two years earlier, in August 1745, [9] he had become Knight of the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George, a distinguished order based in the Basilica of St Mary of the Steccata. This order counted among its Grand Masters aristocrats such as Marie Louise, the Duchess of Parma and Napoleon’s second wife. In 1754 D’Alay made a will and left everything he owned to the Constantinian Order, including his Stradivari violin. He left to his wife Margherita, his son Antonio and the children of his son Gaetano, who had predeceased him, only what was strictly required by law. Tellingly, he stated in his will that the sum resulting from the sale of the Stradivari should be left to the church, with half used for the celebration of masses to pray for his soul, with the other half spent on masses for the soul of Faustina Bordoni.

Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma, who like D’Alay was a member of the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George. In this portrait she is wearing a ribbon with the arms of the order (right)

D’Alay died in 1757 and in the following year the order found a buyer for his instrument in Ferdinando Tondù-Mangani (1713–c.1793). Although of humble origins, the Tondù family had amassed considerable wealth in the 17th century through the production and commerce of textiles. Most of the family members lived in Parma. The Order of Saint George and the Tondù family were related, because the latter held the right of patronage over the Chapel of the Crucifix of the Basilica of the Steccata, the order’s base.

Having acquired the violin, Tondù-Mangani retained possession of it until he died, in spite of all attempts by Count Cozio to buy it. It appears that Eleonora Perego, the widow of Tondù-Mangani, sold the instrument to the Czech composer and violinist Václav Pichl (1741–1805), who, according to the Hills, ‘previous to the year 1800 disposed of it to a man of the name of Frantzel.’ [10] Later on the violin was purchased by the dealer J.N. Durand, who owned other valuable instruments, including at least one viola from the Stradivari workshop, the ‘Cassavetti’ (1727). Not much is known about him. The Hills described him as ‘city merchant’ who ‘appears to have been particularly active, and bought – or had consigned to him – Stradivari instruments from France and Germany.’ [11]

Durand brought the ‘San Lorenzo’ to London and sold it to the foremost violin dealer of his day, John Betts (1752–1823). The list of Betts’ clientele resembled a Who’s Who of society at the time and he can have had no problems in finding a buyer as distinguished as the violin: the Italian virtuoso Giovanni Battista Viotti.

Jerez, home to the Duke of San Lorenzo, shown in c. 1835. Painting: Bibliographic Institute Hildburghausen

It seems that Viotti offered the instrument for sale to the Duke of San Lorenzo in London in 1823, a couple of months before he died. The duke in question was Lorenzo Fernández de Villavicencio Cañas y Portocarrero, Third Duke of San Lorenzo (1778–1859). He had a remarkable art collection in his castle in Jerez de la Frontera and kept this violin, which now bears his name, for the rest of his life. Around the same time the duke was also in possession of ‘another Stradivari dated 1720.’ [12]

The first marriage of the duke with Maria Josefa de Salcedo Cañaveral y Cañas (1783–1837) was childless. Therefore, when the marquise died her husband inherited all her titles. The duke married a second time, Josefa del Corral y Garcia, and had one son, Lorenzo Fernández de Villavicencio y del Corral, 4th Duke of San Lorenzo (1841–1896). Arthur Hill recalled that his brother Alfred made several attempts to meet the duke’s heir around 1895 to obtain definite information concerning the violin, but he was always rejected.

It remains unclear when the violin was sold and by whom. A list of violins sent by J.B. Vuillaume to his brother Nicolas-François on May 6, 1857 includes a violin ‘San Lorenzo’ with a sale price of 1,000 francs, [13] but it seems likely that this was a different instrument, perhaps the Stradivari dated 1720. According to Doring, the duke’s son sold the 1718 violin for a very small sum to an antiquarian of Madrid who, in turn, disposed of it to a dealer and collector of violins called Esclava. [14] [15] Meanwhile the ledger of the French dealers Caressa & Francais lists a Stradivari violin dated 1718 with a Latin inscription on the sides, which was sold by the Duke of San Lorenzo to a M. Sanz for 3,000 pesetas in November 1903. [16] This seems to be ‘our’ violin.

According to Doring, the duke’s son sold the ‘San Lorenzo’ violin for a very small sum to an antiquarian of Madrid

In 1904 an individual described only as a ‘Spaniard’ offered the instrument for sale to the Hills. [17] After lengthy negotiations a deal was struck and, shortly afterwards, Caressa & Francais bought the violin from their London colleagues in order to sell it to M. Dufresne, of Logelbach (in north-eastern France), who was a wealthy amateur. Caressa & Francais regained possession of the instrument not long afterwards and, through the violin house of Hamma & Co. in Stuttgart, it was then acquired by the railway engineer and collector Georg Talbot of Aachen (1864–1948) in 1908. It was Talbot who allowed the violin to be exhibited in Cremona in 1937. [18] After having been bought by a private collector in 2012, this instrument finally joined the Munetsugu Collection of Tokyo in 2015.

Thanks to Dr Mario Corbellini, Daniele Maggetti, Professor Giuseppe Martini, Prince Diofebo Meli Lupi, Professor Corrado Mingardi and Roberto Regazzi, for assistance with source materials.

Alessandra Barabaschi is an Italian art historian and has authored several books including the four-volume ‘Antonius Stradivarius’.

The ‘San Lorenzo’ will be exhibited alongside around 20 other Stradivari instruments as part of the Tokyo Stradivarius Festival 2018, to be held at the Mori Arts Center Gallery in Tokyo, October 9–15, 2018. The festival also includes a series of concerts featuring the instruments in the exhibition.

Notes

[1] Known as Psalm 112 in some translations, including the King James Bible.

[2] Extract from the unpublished diaries of Arthur F. Hill dated 2 January 1909, Antonio Stradivari – ‘San Lorenzo’ 1718, Monograph, J.& A. Beare, London, 2015.

[3] Gregori, Giampaolo, L’Esposizione di liuteria antica a Cremona nel 1937, Editrice Turris, Cremona, 1987, p. 89.

[4] Ernest Doring was also falsely persuaded that the duke had been a contemporary of Stradivari, as he recorded: ‘The violin has an inscription on the sides said to have been executed by Stradivari in compliance with the wish of the Duke’ in How Many Strads? Our Heritage from the Master, Bein & Fushi, Chicago, 1945, reprint 1999, p. 216.

[5] Rosengard, Duane, An early history of the San Lorenzo violin, contained in Antonio Stradivari – ‘San Lorenzo’ 1718, op. cit.

[6] Hart, George, The Violin: Its Famous Makers and Their Imitators, First edition 1875, Reprint Dulau & Co., London, 1909, p. 219.

[7] Bacchetta, Renzo; Iviglia, Giovanni, Cozio di Salabue, Carteggio, Carteggio, Antonio Cordani, Milano, 1950, pp. 353–354.

[8] Lasagni, Roberto, Dizionario biografico dei parmigiani, Editrice PPS, Parma, 1999, vol. 2, p. 301.

[9] Letter from Mauro D’Alay to the Order on the day he was knighted, dated Parma, August 10, 1745.

[10] Extract from the unpublished diaries of Arthur F. Hill, Op. cit.

[11] Hill, W.H.; Hill, A.F.; Hill, A.E., Antonio Stradivari. His Life and Work (1644–1737), W.E. Hill & Sons, London, 1902, reprint 1963, Dover, New York, p. 261.

[12] Extract from the unpublished diaries of Arthur F. Hill, Op. cit.

[13] Vuillaume, Jean Baptiste, Letter to Nicolas-François Vuillaume dated May 6, 1857, reproduced in Violons, Vuillaume, Cité de la Musique, Paris, 1998, p. 108.

[14] Doring, E. N., Op. cit., p. 216.

[15] Doring, Ernest N., How Many Strads?, Violins & Violinists, William Lewis & Son, Chicago, September 1940, pp. 55–56.

[16] Sale Book, 1870–1936, The Jacques Francais Rare Violins, Inc. Photographic Archive and Business Records, 1844–1998, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, p. 148.

[17] Extract from the unpublished diaries of Arthur F. Hill, Op. cit.

[18] Gregori, G., Op. cit., p. 89.