The name Roger N. Chittolini is associated with many fine instruments, including the ‘Lipinski’ Stradivari and various others. He was clearly a tenacious, independent spirit, having built a successful career as a musician, collector and dealer of fine instruments during the most turbulent period of the 20th century. He traded with the most respected and notable dealers and collectors of his time, such as Erich Lachmann, Emil Herrmann, Rembert Wurlitzer, William Lewis & Son and Lyon & Healy. Yet until now almost nothing has been written about his life.

Roger Nestor Chittolini (pronounced key-toh-lee-nee) was born Ruggero Nestore Chittolini in 1881, the son of Francisco Chittolini and Cleonice Minyori. His early years were spent in Brescello, Italy, a commune in the province of Reggio Emilia about 80 km northwest of Bologna. Family and friends called him Nestore (Nestor). He emigrated to America aged 24, departing from Le Havre, France, on January 13, 1906 with his mother and sister Emma and arriving at Ellis Island, New York, ten days later. [1] Perhaps the family realized in the years leading up to World War I that Italy, then a newly unified nation, was in crisis and that it was time to pack up and set sail to a new life in America.

The Chittolini family settled in Kansas, where Roger was soon to meet his future wife, Sarah Pucci. Pucci was also an Italian immigrant who had arrived in America with her family in 1897. They married on May 3, 1908.

As the family was settling in, the first record of employment for Roger Chittolini in America shows him performing as a violinist and director of his own five-piece orchestra as well as teaching violin. In 1908 the Pittsburg (Kansas) directory listed ‘Chittolini’s Orchestra, R.N. Chittolini director, 121 W. Jefferson Av.’ Chittolini also opened a violin studio in Pittsburg where he offered violin lessons. He ran adverts in the Pittsburg Daily classified section in November 1909: ‘Prof. R.N. Chittolini Violin Studio, 611 North Broadway, Over Palace Drug Store.’

That same year his eldest daughter, Geraldine R. Chittolini (1909–1983), was born. She was later known as Geraldine Souvaine and became the Metropolitan Opera’s highly successful radio broadcast producer from 1955–1981. In 1913 his second daughter, Francesca, was born. She became a professional actress known as Francesca Lenni (1913–1967).

With a large family to feed, including his mother and sister, Chittolini found work as a violinist in the orchestra of the Orpheum Theater in Kansas City. [2] The Orpheum was known as the birthplace of vaudeville, with star attractions including Will Rogers, Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor and Sarah Bernhardt.

During the ‘Roaring 20s’ Chittolini was witness to dramatic social and political changes, as economic growth swept the nation. America was becoming an affluent consumer society and there was no better place to be than in a big city. It was at this point that Chittolini must have realized that rather than ‘bowing for dollars’ there was a fortune to be made in the violin trade, and he set his sights on New York City.

A violin by J.B. Vuillaume, Paris 1860, which Chittolini owned in the 1940s. Photos: Tarisio

More photosBy 1925 Chittolini was living at 316 West 71st Street, New York, [3] and shortly afterwards he established himself just across the street from Carnegie Hall, at 153 West 57th Street (what is now the Park Hyatt Hotel) as R.N. Chittolini Inc. Rare Old Violins. The opulence of these ‘années folles’ (crazy years) came to an abrupt end with the stock market crash of 1929. Nevertheless, while the rest of America was slipping into the Great Depression, Chittolini was amassing and trading an extraordinary collection of rare Italian masterpieces and fine French bows, while building up a network of dealers and affluent clients. According to violin historian Philip Kass, he employed at least two Italian violin makers in his workshop: Giuseppe Martino (1882–1970) and Jago Peternella (1886–1970).

During this immense global crisis Chittolini saw opportunity and seized it

It is evident that during this immense global crisis Chittolini saw opportunity and seized it. Although the fine instrument businesses that survived the depression seemed to be mainly the big houses, he remained an independent and successful dealer–collector until his retirement. He owned many fine Cremonese violins and at the height of his career his collection comprised over 35 instruments by Stradivari, Guarneri, Amati, Guadagnini, Bergonzi and Storioni among others. His Stradivari violins included the 1666 ‘Aranyi’, 1683 ‘Madame Bâtard’, 1691 ‘Ginn’ and 1715 ‘Lipinski’. (See Cozio’s list of instruments owned by Chittolini)

The provenance of the instruments that passed through his hands demonstrates that he built solid long-term relationships with clients. As well as the leading dealers of the era, Chittolini’s clients included musicians such as the violinist Milan Lusk (a recording artist for Victor, Edison and Columbia Records), Ben Stad of Philadelphia (a violinist, conductor and avid collector) and Michael Rosenker of the New York Philharmonic.

The ‘Lipinski’ Stradivari of c. 1715 was part of the Chittolini collection from 1937–1941. Photo Michael Darnton, courtesy Frank Almond

More photosHere are some examples:

‘Lipinski’ Antonio Stradivari violin, Cremona, c. 1715

Prior to Chittolini’s ownership, it belonged to the virtuoso violinist Milan Lusk of Chicago. Chittolini owned the instrument from 1937 until 1941, when he sold it to Dr Martinez Canãs of Havana, Cuba.

‘Madame Chappey’ G.B. Guadagnini violin, Parma, c. 1770

This violin came to the USA in the 1930s, when it was acquired by Wurlitzer and illustrated in their 1931 catalog. Chittolini owned the instrument in 1944 and in December of that year sold it to Allen Wertz through Frank J. Callier.

‘Chittolini, Petersen’ Carlo Annibale Tononi violin, Venice, c. 1730

This violin was sold by Nathan E. Posner (a Beverly Hills collector of rare instruments) in 1935 to the collector Thomas C. Petersen, a successful San Francisco textile manufacturer and an avid collector of rare musical instruments, who subsequently sold it to Chittolini.

‘Paganini, Vuillaume’ Carlo Bergonzi violin, Cremona, c. 1720

According to Emil Herrmann, by 1930 this violin was in the collection of Thomas C. Petersen. Petersen sold the violin to Chittolini in 1948, who then sold it via Herrmann to John Corigliano, concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

‘Lachmann, Schwechter’ G.B. Guadagnini violin, Turin, c. 1776

Emil Herrmann sold this instrument to Roger Chittolini, from whom it was then acquired by Erich Lachmann.

‘Chittolini’ Giacomo Rivolta cello, Milan, 1822

This cello was sold to Chittolini by Wurlitzer. Chittolini owned the instrument for nine years and sold it back to Wurlitzer in 1944.

‘Trombetta’ Carlo Bergonzi violin, Cremona, c. 1725–31

Chittolini acquired this excellent example from the prominent Los Angeles collector E. Clem Wilson, subsequently selling it in 1945 to Michael Rosenker, associate concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic. Rosenker owned the ‘Trombetta’ until his death in 1996. According to his son Misha, also a violinist, Rosenker purchased several instruments from Chittolini, as well as bows by Dominique Peccatte and Jean Pierre Marie Persoit.

Misha recalled a story his father shared with him about the ‘Trombetta’ Bergonzi. From the 1930s his father had been friends with David Oistrakh, who tried out the Bergonzi and was so impressed with its playability that he wanted to buy it, but to no avail. Then in 1955 Oistrakh arrived in New York to make his American debut appearance, premiering the Shostakovich Concerto no.1 at Carnegie Hall.

Writing for International Record Review in 2000, the music critic Harris Goldsmith recalled the second performance on December 30: ‘At the Friday afternoon concert, Oistrakh broke a string during the finale and had to swap violins with Michael Rosenker, the assistant concertmaster, while the latter had to re-string the great Soviet virtuoso’s own instrument.’

Next to Rosenker on the front desk was the concertmaster John Corigliano, whose violins included the c. 1716 ‘Baron Wittgenstein’ Stradivari and the ‘Paganini, Vuillaume’ Carlo Bergonzi c. 1720 (sold to him by Chittolini as we have seen). When Oistrakh’s string broke, however, he reached for Rosenker’s violin, perhaps believing it to be the ‘Trombetta’ Bergonzi, and proceeded with the performance. Ironically, on that particular day Rosenker was playing his Pierre Joseph Hel violin.

Chittolini also had notable relationships with affluent private collectors including:

Austin T. Levy of Rhode Island, a successful textile manufacturer, who was a truly progressive reformer of advanced concepts in business and philanthropic contributions.

Alfonso Marconi, an Italian businessman and collector of stringed instruments, most famous for assisting his brother Guglielmo Marconi in his pioneering work on long-distance radio transmission.

Mario Porazzi, a Wall Street businessman, who trained as a violinist with Joseph Allegro and became an avid collector. In 1947 alone he bought six fiddles from Chittolini.

Dr Eugenio Sturchio, an avid collector of many Stradivari violins as well as Guarneri and Guadagnini

Dr F. William Sunderman of Philadelphia, who bought the 1694 ‘Irish, Maaskoff’ Stradivari from Chittolini via Wurlitzer in 1954. He was a doctor and scientist who lived to the age of 104, played his Stradivari violin at Carnegie Hall at 99 and was honored as the nation’s oldest worker at 100. He developed a method for measuring glucose in the blood, the Sunderman Sugar Tube, and was one of the first doctors to use insulin to bring a patient out of a diabetic coma. In World War II he was a medical director for the Manhattan Project, which developed the atomic bomb.

E. Clem Wilson, who made his fortune in the manufacture of patents in oil well tools and machinery and became an avid collector of rare instruments. Many of his instruments are now in the Julliard Collection.

Another important Chittolini client was Ansley K. Salz, a prominent San Francisco businessman and collector of fine instruments, who donated his collection to the Music Department of the University of California, Berkeley, in 1964. Among the instruments Chittolini sold Salz was the ‘Laurie’ Santo Seraphin violin of c. 1740 (which he later sold to Eunice Wennermark Price). An article from May 1947 shows that Chittolini had shipped violins by Nicolò Amati and Francesco Rugeri to Salz. The instruments unfortunately disappeared en route to San Francisco, as the Ogden Standard-Examiner of Utah reported on May 20, 1947:

Two Rare Violins Disappear From Westbound Train SAN FRANCISCO, May 20

The Railway Express Agency reported to police today that two rare violins shipped from New York had been stolen en route to their San Francisco destination. The violins, one a Nicola Amati of Cremona and the other a Francesco Ruggieri (worth $18,000), were shipped by R. N. Chittolini, New York dealer ‘in rare musical instruments’, and were for Ansley K. Salz, a San Francisco collector. Express agents said the violins were checked at Ogden, but were missing when the train arrived here (San Francisco). Special investigators for the Railway Express Agency were in Ogden today investigating the theft or loss. Weber county-sheriffs officers and the representatives of the FBI were cooperating.

Various instruments still bear the Chittolini name, such as the ‘Chittolini’ Giacomo Rivolta cello mentioned earlier. The well-known ‘Lachmann, Schwechter’ Guadagnini was listed as ‘ex-Chittolini’ in the Emil Herrmann catalog. [4] There are other Chittolini instruments listed by Herrmann, such as the ‘Chittolini’ Carlo Giuseppe Testore cello c. 1700, and a ‘Chittolini’ Giovanni Francesco Pressenda violin. Presumably the Chittolini name gave a certain cachet to the instruments that bore it.

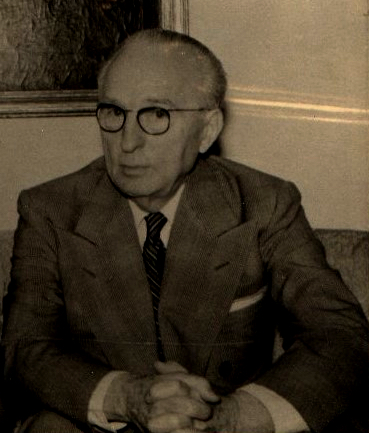

The Chittolini family in c. 1958. Standing from left: John Land Sr, Fannie Hall Land, Roger Nestor Chittolini. Seated from left: Bill Land, Sarah Avaline Chittolini and Sarah Land. Photo courtesy John Land

After the death of his first wife in 1955, Chittolini soon met his second wife, Sarah Avaline Saufley (1903–1978). In 1958, after many fruitful years as a violin dealer, he retired and settled in Christiansburg,Virginia. Philip Kass recalls that Herbert Goodkind had an ornate carved mantelpiece in his home in Larchmont that had come from the Chittolini shop when Chittolini retired.

Chittolini died on June 30, 1959 aged 77 and is buried at Sunset Cemetery in Christiansburg, Virginia. He was survived by his two children from the first marriage, Geraldine and Francesca, his second wife Sarah and his step-children, Fannie Hall Land (1924–1960) and Robert C. Hall (1922–1986).

I was fortunate to connect with John Land (Fannie Hall Land’s youngest son). He writes: ‘…my Grandmother… was married to Roger N Chittolini (whom I knew as Nestor) until his death on 30 June 1959… I remember visiting their home in or near Christiansburg, Virginia, where he had a walk-in safe in the basement, full of violins. I also remember the headboard of their bed was carved wood with violins carved into it… I have only two photographs of Nestor and Avaline, which I have included below… the second photo shows my father John, my mother Fannie, and Nestor in the back, and my brother Bill, Avaline, and my sister Sarah in front. I was probably taking the picture…’

Thanks to John Land, Misha Rosenker, Philip Kass and Christopher Reuning.

Gennady Filimonov is a violinist in the Seattle Symphony and founder of Filimonov Fine Violins.

Notes

[1] Ellis Island records, from the Ellis Island Database.

[2] Chittolini’s Registration Card of 1918.

[3] The US Census of 1930 listed him as the owner of his own dwelling.

[4] Emil Herrmann catalog, c. 1940s, vol. 2, p. 196.

Reference sources

Cozio archive

US Census: 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940

ancestry.com

lifeinitaly.com

New York Times

Radford News Journal, 1959

Rome News Tribune, June 4, 1976

Reference books

Ernest N. Doring, The Guadagnini Family of Violin Makers, Dover Publications, 1949 (reprint).

Ernest N. Doring, How Many Strads?, Bein & Fushi, 1999.

W. Henry Hill, Arthur F. Hill, Alfred E, Hill, Antonio Stradivari: His Life & Work, Dover Publications, New York, 1963.

Horace Petherick, Antonio Stradivari, Scribner, New York, 1900.

Herbert Goodkind, Violin Iconography of Antonio Stradivari, 1972.

The Emil Herrmann Collection, Darling Publications, 2006.

Christopher Reuning, Carlo Bergonzi – A Cremonese Master Unveiled, Cremona, 2010.