To enter Rodolfo Marchini’s home is to enter his world. His life is encapsulated here, particularly in the workshop, where historic violin making documents and photographs, tools, violins and mandolins galore share space with dolls’ house furniture and a collection of toy soldiers. Marchini was a school friend of Giuseppe Lucci’s daughter, Raffaella, and she would later become his wife. They now live in what was the Lucci family home and workshop. It was here that Rodolfo, under the gaze of his master, picked up his tools for the first time and metamorphosed into a master himself. The workbench is not large – less than two metres long – and at its feet, about a metre apart, are two broken floor tiles, their cracks a testament to the decades these two makers spent working alongside each other.

Marchini is in love with the past. He delighted in revealing to me the glories of post-war Rome in which he was born and raised – glories that I felt to him had more in common with ancient Rome, a paragon of culture, architectural splendour and organisational capacity, than anything on offer from his beloved capital today, with its local government in turmoil and its streets crowded with tourists. Secluded behind the double glazing in the stillness of this apartment, one was very aware of the lives that had been lived in these rooms, the walls and furnishings steeped in their memories. And at its epicenter was Marchini, energetic, genteel and eager to communicate, freely allowing his emotions to draw on the reserves of the past.

In the following interview Marchini’s words are translated from the original Italian.

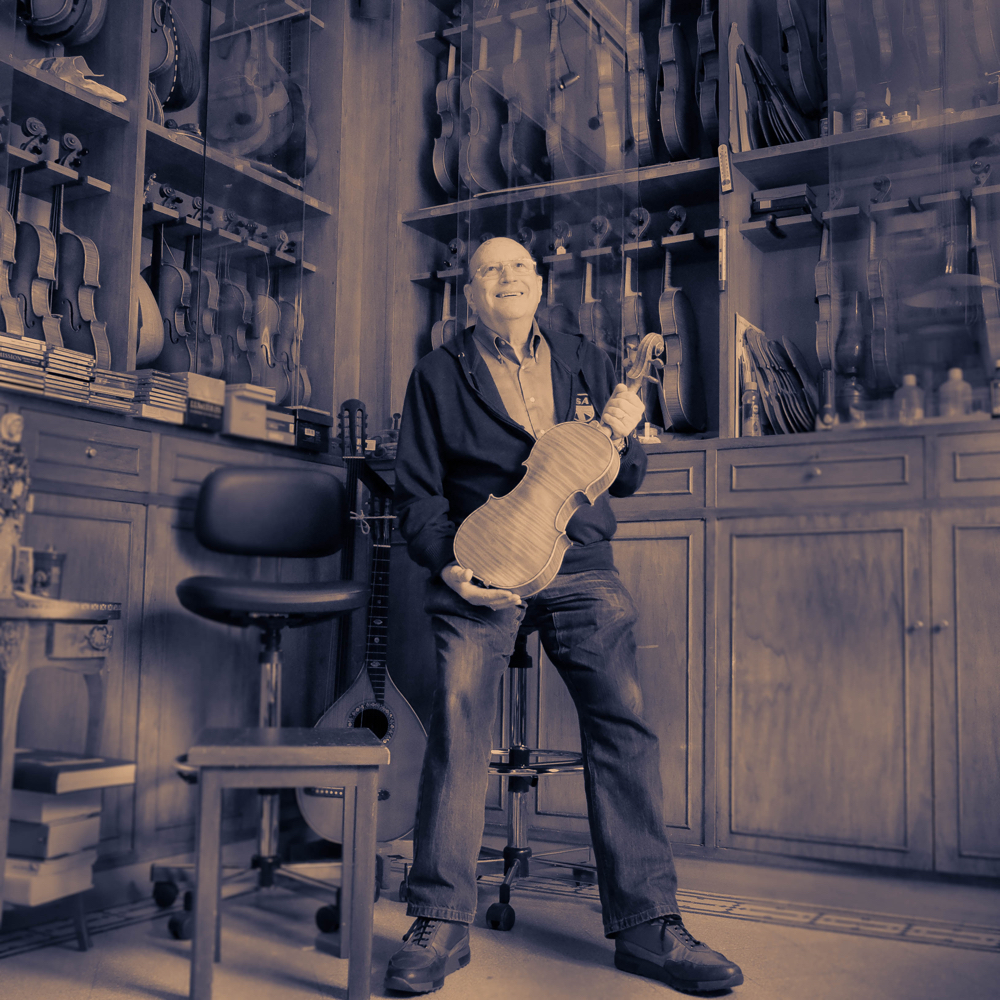

Marchini in his workshop, where he used to work alongside Lucci. Photo: Paul Sadka

My joining Lucci was almost an act of destiny. I used to come to this house when I was dating Lucci’s daughter Raffaella in the 60s. I came one time and he was taking off a cello fingerboard. He was holding a knife and and while he was pulling the fingerboard away it slipped and took his finger off. He had cut the tendon. I was a bit of a specialist when it came to metal because I was studying precision mechanics and he said, ‘Listen, Rudolfo, if you don’t help me here I can’t go on working. At least help me out till I get better.’ So I started to help him and once he’d recovered he said I could go. But I kept coming back to see his daughter, and then he said, ‘But you’re good, you’ve got a good eye – perhaps it’s better if you stay here.’

My parents were angry with me, ‘What are you doing with this violin making stuff?’ But at that time it wasn’t like now, where the instruments are all coming out of the same mould. I’m an expert, but if you show me an instrument from Cremona I can’t tell one from another; they’re all the same. However, at that time there was the Milanese school, the schools of Ferrara, Naples and Tuscany. Each one distinct. Rome had a beautiful school of making. First Giuseppe Fiorini then Giuseppe Rossi, Simone Sacconi and Enrico Politi, and then Rodolfo Fredi and Lucci. It was a nice group of maestri. And Sacconi was the best.

Sacconi came here every year to this workshop. He wanted to take us away with him. ‘Come!’ he said. ‘I’ll take you to Wurlitzer.’

Sacconi came here every year to this workshop. He was a wonderful person, wonderful. He wanted to take us away with him. ‘Come!’ he said. ‘I’ll take you to Wurlitzer.’ But I couldn’t leave my father-in-law, it would have been ungentlemanly. Sacconi bought many instruments from us and he bought back the instruments that he’d made here in Rome. We sold many of our instruments through him and we made our living through the instruments he bought for Wurlitzer. I used to know all the biggest makers of the period. Ferdinando Garimberti – he had kidney stones and went to Fiuggi to do the cure of the waters there, and then he came here to eat with us. Giuseppe Ornati – I’ve got the toys that he made for his daughter. He made all this dolls’ house furniture by hand for her, but she died unfortunately. And so he gave it to my wife. When Ornati died he left a diamond brooch to Lucci in his will, and I’ve got that now. Lucci also got to know perhaps the best pupil of the Bisiachs: Pietro Borghi. He was better than the Antoniazzis, the best by far. And so he got to know Borghi and studied with him. Bisiach, Borghi, Lucci, Marchini – I’m a direct descendant of the Bisiachs.

In the workshop, Marchini’s tools share space with the dolls’ house furniture made by Ornati for his daughter. Photos: Paul Sadka

What sort of relationship did I have with Lucci? Mamma mia, he was nasty! He was a man of the 19th century. He didn’t joke, he was very serious, and until his death we used Lei [the formal version of ‘you’ in Italian] to each other. ‘No pupils,’ he used to say. ‘The fewer pupils you have the better it is. Otherwise you destroy violin making. One pupil, two maximum. When he used to speak to other master makers of the time he used to reproach them. ‘Basta con gli allievi – enough already with the pupils – you mustn’t take them on, it’s a mistake, it will be a disaster later.’

Lucci came here at 8.30 every morning to start work and worked until one in the morning. Even on Saturday. He never stopped working

If the work didn’t go well, he got angry. I remember when I was starting off, he said, ‘You have to make a cello.’ I didn’t know wood much and I took this table blank for a cello and I began to gouge it out. After a while with a thrust of the gouge I broke off one of the corners and it dropped onto the floor. Mamma mia, how he started to swear – everyone was trying to find the piece on the floor. ‘You’ve ruined the whole table!’ he shouted. Finally he found it and it was glued on and you couldn’t tell, but it was hard at the time. Spending 30 years with him made me depressed. You couldn’t live with him, it was impossible! He came here at 8.30 every morning to start work and worked until one in the morning. Even on Saturday. He never stopped working. He died at the bench. He was happy there – he never even went to the bar for a coffee. On Sunday, he went to church in the morning and then he worked till 3 in the afternoon. At 3.30 Raffaella and I were allowed to go to the cinema but then it was straight back to work. This was a luxury he felt he was offering us. No one was watching television here, just work, work, work. It was hard for me.

‘Lucci was a man of the 19th century. He didn’t joke, he was very serious,’ says Marchini. Photo: Paul Sadka

The varnish that I use is the Italian one. Today the varnish that they’re using in Cremona is much more like the French varnish, not the classical Italian one. In the 19th century French makers tried the varnish of the Italians that they’d found in books but couldn’t manage it, and so they made their own varnish, which is really easy to apply. Italian varnish is different – you need to know where you’ve put each brush stroke and you need to put it close to the previous one and you can’t see it because it’s transparent like glass. And if you make a mistake and put it too close you brush the former stroke off. It can drive you mad. I believe that’s the type of varnish Stradivari used. Our varnishes are all natural. A long time ago Lucci bought loads of those natural substances in the east. He bought enough for his whole life. I also have wood for the whole of my life, wood a hundred years old that Lucci bought 50 years ago – and it’s a pity because I won’t be able to use all that wood ever.

I have had a pupil, not one who has worked alongside me but we spoke a lot. And so the line through Lucci will continue. It would have been a shame if it had finished with me. He’s become the violin maker of the Rome conservatoire, so it’s gone well for him. He’s getting pupils. But let’s talk frankly – this profession is finished. For me, it’s finished. No one uses the gouges now. And they‘ve got the machines for purfling. I always handmade my purling from ebony.

Ahhh, how fortunate is he who has seen Rome in the old days. The streets were all free. The carts with the horses were going around for the tourists and the Colosseum was full of grass. It was wonderful, a paradise. There was no danger on the streets. As children we played unaccompanied in the gardens. My first meeting with Raffaella was in the Giardino del Rinascaia. It was all so clean, no litter. Rome in the 60s was like walking into a museum, everyone on vespas. I didn’t have a motorbike because at my house they were afraid for me.

I thank God I got to know Lucci and his daughter because I’ve had the chance to be part of this profession. This house was my life. I lived more with Lucci than with my father and mother. And I was close to the wife of Lucci too, right till the end. When she died recently I was completely shocked. They all died – my father, my mother, Lucci – and then it was only her left. My wife and I haven’t got brothers and sisters or children – nothing. I’ve said to Raffaella, if I get ill I want to die here, in this house, like your father died. It was a good union me and him. Every day I light a candle for him, of course.

Paul Sadka is an award-winning bow maker currently working in France.

Rodolfo Marchini inherited the workshop he had shared with Giuseppe Lucci upon the latter’s death in 1991. A cello made by Giuseppe Lucci in 1974 is among the highlights of our March London auction. Catalog online February 28.