I set off on the 45-minute drive from Cremona to Parma to interview Renato Scrollavezza not knowing quite what to expect. A quiet, flat, tranquil stretch of land separates this violin maker – a rare thing in the province of Parma – from his contemporaries in the city of Cremona, where in particularly hot summers they have been known to swarm.

Scrollavezza’s residence has a delicate, almost aristocratic charm about it. It is a place where the air is charged with a respect for the way things used to be done and it brings to mind the opening line of L.P. Hartley’s novel The Go-Between: ‘The past is a foreign country, they do things differently there.’

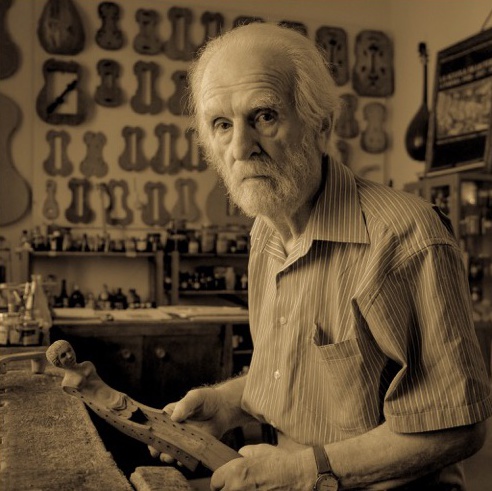

The portrait taken on the day of the interview is not representative of Scrollavezza, the intense, industrious maker of the second half of the 20th century. It is perhaps rather a testament to the resilience and strength of a man who has given his life to the violin and still keeps his workshop in Parma operational, ready to be worked in should the need arise, despite the weathering of age and illness.

I was privileged to bear witness to the intense emotion and fervor that this man transmitted through his now frail and querulous voice – in particular the tears shed in vivid memory of the love his mother had shown seven decades ago as she attempted to protect her children from the physical horrors of war in the fields around Noceto in the province of Parma.

In the following interview Scrollavezza’s words are translated from the original Italian.

I used to imagine the workshop of Stradivari, which has always been of interest to me. You can imagine him as the maestro in charge of the workshop, the absolute boss who knows how to teach and to mould pupils, passing down real knowledge, understanding and imagination. That’s how I like to imagine it. ‘You do it like that, like this,’ he would say.

I’ve always been shy and said very little. That’s why I speak out now, imagining this old approach between the master and pupil. I created a very liberal school – as my daughter can confirm, since she went to it – with master and pupil on equal terms. Even so I managed to create excellent pupils who didn’t lose respect for me despite the familiarity. I created a school in which I spoke about everything – painting, sculpture, architecture and to a certain extent the applied arts. It seems to me that we need to move into the future while always looking to what has gone before.

Renato Scrollavezza’s workshop. Photo: Paul Sadka

I didn’t plan to open a school. I never dreamed of teaching. At that time the president of the Parma Conservatoire was Giorgio Paini. One day I was in the conservatoire and I saw him with the bursar, looking around the building. He caught sight of me and he burst out loudly with, ‘Scrollavezza, come here!’ – he had a very overbearing manner – ‘We must have a violin making school here!’ I was so surprised. But a few days later he asked me to go and talk with him about it in private. Six months later he had the blessing of the government in Rome.

Once I began to teach, a whole new world opened up for me. I would have never believed it because I’m so shy, but I simply fell in love with giving something to others. And I began to understand that one must do things with compassion and love and that whoever puts this quality into his actions has done something good and beautiful.

Violin makers look far too superficially at the flame of the wood – but being that concerned about what the wood looks like is wrong, even if Stradivari did it too. The wood is interrupted by the flame; you get the flame because the wood is interrupted. The fibres are not in line like the walls of a cylinder but undulating and crossing those walls – the pattern is the natural result of cutting the wood that way. So makers are looking for beautiful wood and relying on the players to use their eyes rather than their ears. Stradivari made several instruments, mainly cellos and a few violas, in poplar and willow because it is the best wood for bringing out that rich, outstanding tone.

Stradivari was famous in his lifetime remember, the nobility treated him like a prince. His instruments were as they were intended to be as soon as they were made. They didn’t sound so good because they were old, because they had been seasoned, or played in; they were perfect as soon as they were finished.

‘Violin makers look too superficially at the flame of the wood. Being that concerned about what the wood looks like is wrong, even if Stradivari did it too’

To be a violin maker you need the sensitivity of the musician – you need to understand the thicknesses, the curves. In Milan when I was young in the 1950s, there were the best violin makers in the world but the instruments didn’t sound the way the soloists wanted. They were made really well, with a beauty to die for, like Greek sculptures. However, when a musician picked one up to play, no warmth came out – it was rigid and didn’t speak or vibrate. They’ll end up hating me, but I was selling violins when the greats couldn’t. They were living off bridges, soundposts, tailpieces.