I set off on the 45-minute drive from Cremona to Parma to interview Renato Scrollavezza not knowing quite what to expect. A quiet, flat, tranquil stretch of land separates this violin maker – a rare thing in the province of Parma – from his contemporaries in the city of Cremona, where in particularly hot summers they have been known to swarm.

Scrollavezza’s residence has a delicate, almost aristocratic charm about it. It is a place where the air is charged with a respect for the way things used to be done and it brings to mind the opening line of L.P. Hartley’s novel The Go-Between: ‘The past is a foreign country, they do things differently there.’

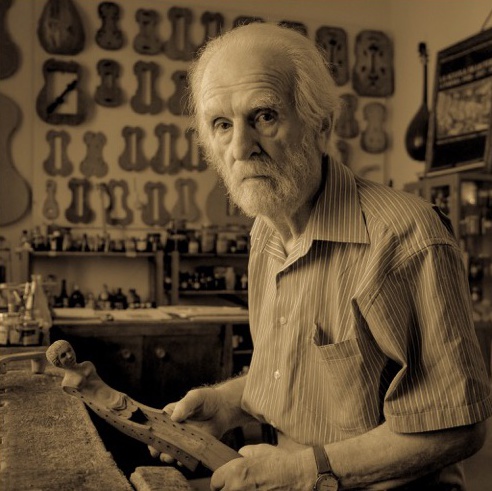

The portrait taken on the day of the interview is not representative of Scrollavezza, the intense, industrious maker of the second half of the 20th century. It is perhaps rather a testament to the resilience and strength of a man who has given his life to the violin and still keeps his workshop in Parma operational, ready to be worked in should the need arise, despite the weathering of age and illness.

I was privileged to bear witness to the intense emotion and fervor that this man transmitted through his now frail and querulous voice – in particular the tears shed in vivid memory of the love his mother had shown seven decades ago as she attempted to protect her children from the physical horrors of war in the fields around Noceto in the province of Parma.

In the following interview Scrollavezza’s words are translated from the original Italian.

I used to imagine the workshop of Stradivari, which has always been of interest to me. You can imagine him as the maestro in charge of the workshop, the absolute boss who knows how to teach and to mould pupils, passing down real knowledge, understanding and imagination. That’s how I like to imagine it. ‘You do it like that, like this,’ he would say.

I’ve always been shy and said very little. That’s why I speak out now, imagining this old approach between the master and pupil. I created a very liberal school – as my daughter can confirm, since she went to it – with master and pupil on equal terms. Even so I managed to create excellent pupils who didn’t lose respect for me despite the familiarity. I created a school in which I spoke about everything – painting, sculpture, architecture and to a certain extent the applied arts. It seems to me that we need to move into the future while always looking to what has gone before.

Renato Scrollavezza’s workshop. Photo: Paul Sadka

I didn’t plan to open a school. I never dreamed of teaching. At that time the president of the Parma Conservatoire was Giorgio Paini. One day I was in the conservatoire and I saw him with the bursar, looking around the building. He caught sight of me and he burst out loudly with, ‘Scrollavezza, come here!’ – he had a very overbearing manner – ‘We must have a violin making school here!’ I was so surprised. But a few days later he asked me to go and talk with him about it in private. Six months later he had the blessing of the government in Rome.

Once I began to teach, a whole new world opened up for me. I would have never believed it because I’m so shy, but I simply fell in love with giving something to others. And I began to understand that one must do things with compassion and love and that whoever puts this quality into his actions has done something good and beautiful.

Violin makers look far too superficially at the flame of the wood – but being that concerned about what the wood looks like is wrong, even if Stradivari did it too. The wood is interrupted by the flame; you get the flame because the wood is interrupted. The fibres are not in line like the walls of a cylinder but undulating and crossing those walls – the pattern is the natural result of cutting the wood that way. So makers are looking for beautiful wood and relying on the players to use their eyes rather than their ears. Stradivari made several instruments, mainly cellos and a few violas, in poplar and willow because it is the best wood for bringing out that rich, outstanding tone.

Stradivari was famous in his lifetime remember, the nobility treated him like a prince. His instruments were as they were intended to be as soon as they were made. They didn’t sound so good because they were old, because they had been seasoned, or played in; they were perfect as soon as they were finished.

‘Violin makers look too superficially at the flame of the wood. Being that concerned about what the wood looks like is wrong, even if Stradivari did it too’

To be a violin maker you need the sensitivity of the musician – you need to understand the thicknesses, the curves. In Milan when I was young in the 1950s, there were the best violin makers in the world but the instruments didn’t sound the way the soloists wanted. They were made really well, with a beauty to die for, like Greek sculptures. However, when a musician picked one up to play, no warmth came out – it was rigid and didn’t speak or vibrate. They’ll end up hating me, but I was selling violins when the greats couldn’t. They were living off bridges, soundposts, tailpieces.

The violin maker’s quality stimulates his individuality – it’s then that you can recognise the hand, the style and the character without the label. The tendency now is to make them all the same, they’re copying each other. There’s an accepted style and that’s fine for as long as it lasts.

It was easier in the old days. I’ve lived through crisis – the extreme poverty that was handed down from century to century since the middle ages. There was only a renaissance for the gentry, for the wealthy. The masses for centuries lived in wretched poverty. I am a part of the mass – but the truth is that these days we’re all too rich and throw everything away, how disgusting!

During the Second World War we escaped from the bombing to the fields. My mother fled there at night time with her sons. She died young partly because of the fear – she cried all the time. Hiding with us in the irrigation ditches alongside the fields, she cried. There was an aeroplane – Pippo it was called – with search lights scanning the fields at night, where there were no military targets, shooting the people. War is horrendous. Anyway, there was a famine, and I was 50 kilos when I went for my military medical at 18. I had no teeth; they were wrecked due to the poverty. Wwe used to gather the ears of wheat that fell from the harvested sheaves in the fields. However, in the old days there was always the joy of living itself – we were happy playing with a ball made of rags.

Renato Scrollavezza keeps his workshop tools and materials in constant readiness despite his now frail health. Photos: Paul Sadka

I ate in a restaurant for the first time in 1963. Actually, I have always eaten hardly anything, as I preferred to buy something beautiful with the money, something from the 18th or 19th century. I got the contents of my house together piece by piece.

I’ve had various jobs. I started work aged seven – it wasn’t just me, everyone did that. Anyone learning a trade went to a workshop in town. And for 20 years I worked on Sundays and holidays. When I got married at 39 that’s what I did. But I felt the need to respect the responsibility of having children and I did my best to do weekends, become ‘normal’. I used to take my family to the seaside and then come back to work. I found it boring on the beach. I’ve done everything to be normal, not be too original. However, my hair was shoulder length and in 1961 I had a beard. There wasn’t another soul with a beard, it took courage. But then it became the fashion in the 70s.

In the old days, you obeyed your father – it was simple, you could say. There have always been the rebellious ones, but their protestations were drowned at birth. Few actually rebel when they are trying to be themselves, to do something that appeals to them, but their father wants them to do something else. There are many more now, but in the old days it was far easier to get smothered. Knowledge and tradition was a way of understanding your culture, your surroundings. However, now thanks to television everyone thinks they know, that they understand.

Renato Scrollavezza died in October 2019.

Paul Sadka is an award-winning bow maker currently working in France.