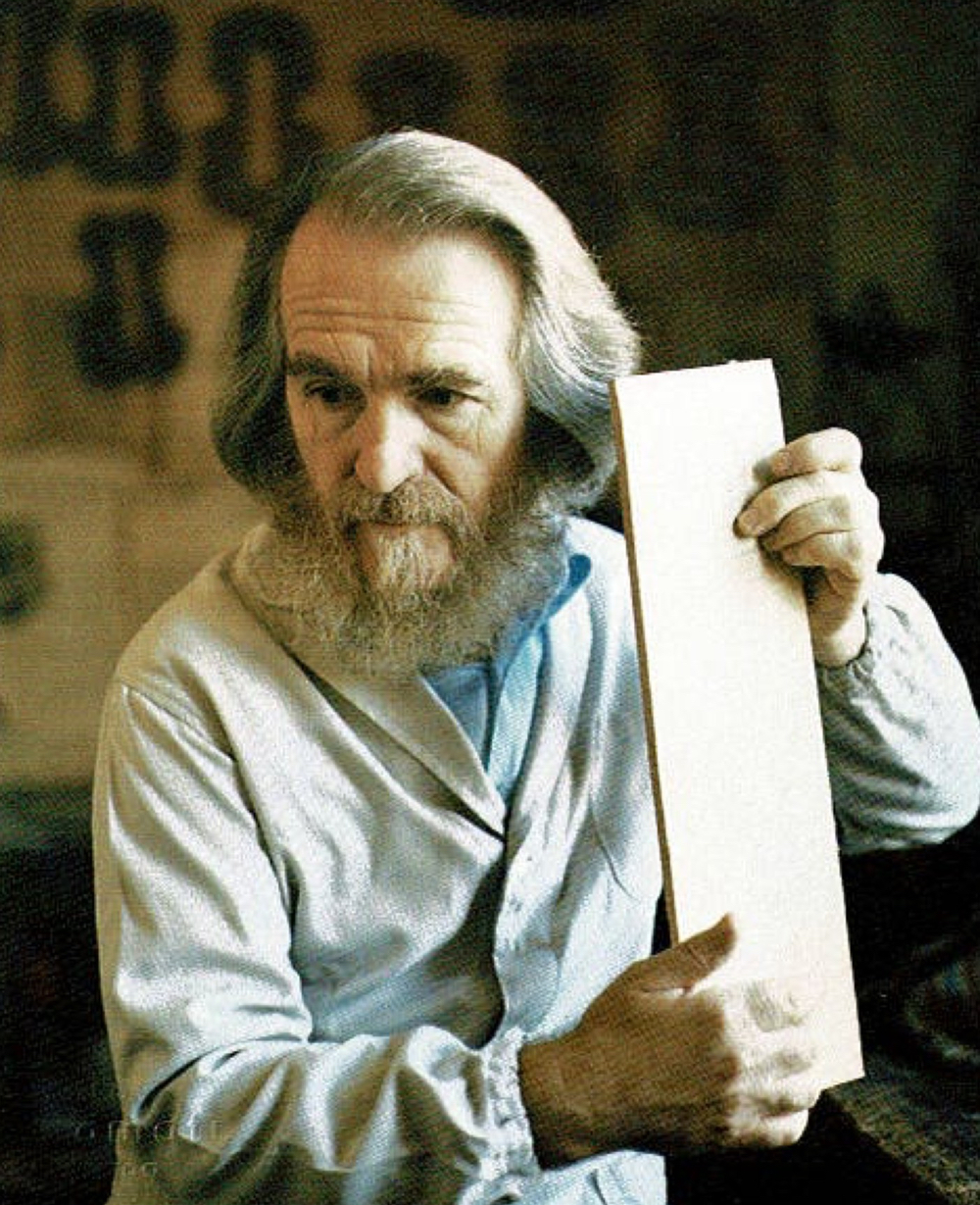

Renato Scrollavezza was a man from another era. He spoke softly but with a directness, avoiding pleasantries and with an almost poetic flourish. With his signature long white hair and beard, you could put him in a top hat and mistake him for Verdi. But this wasn’t pretense or posturing, it was his character.

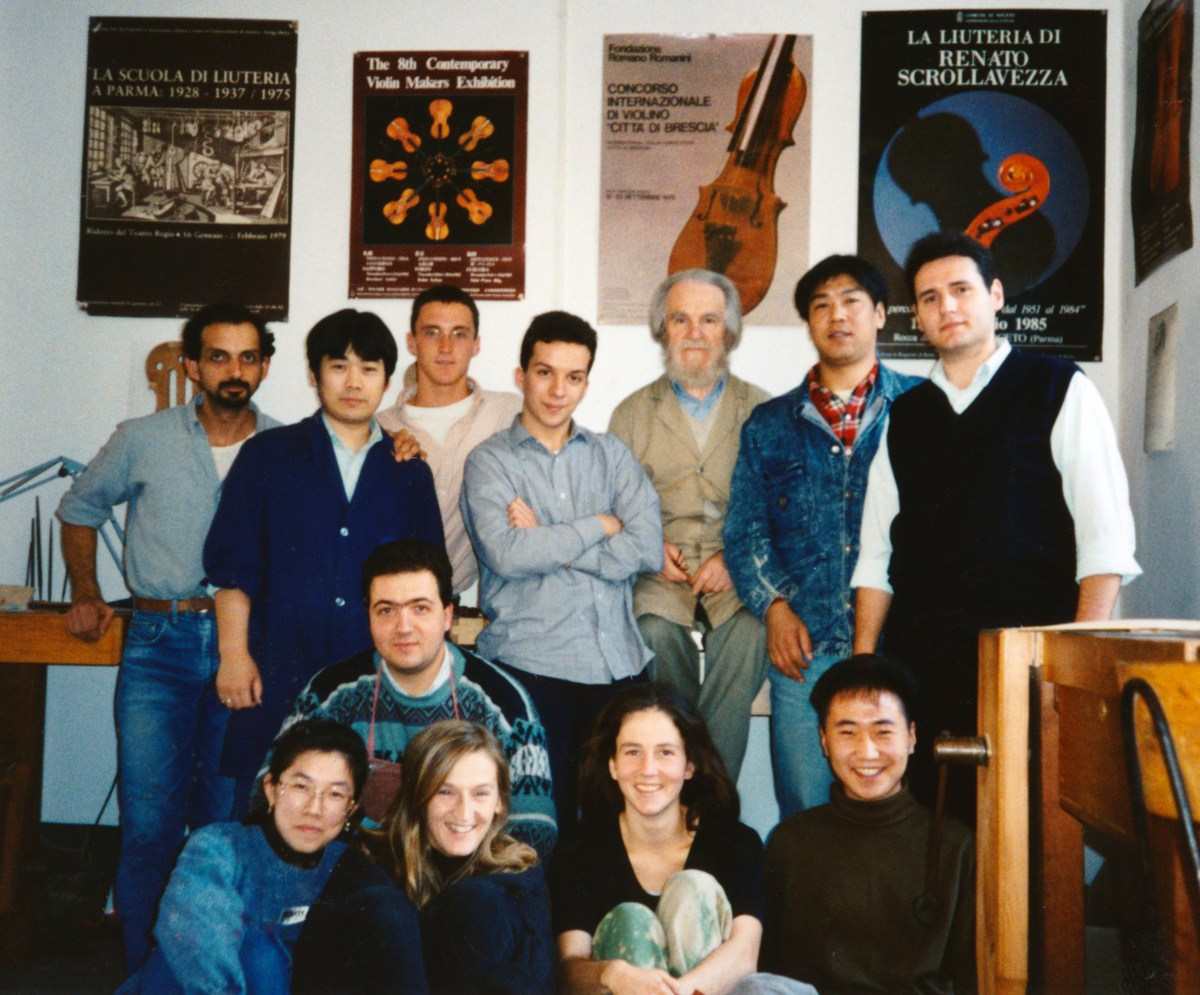

I studied with Renato for one year from September to May of 1995–96. Every Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, Renato held court in his white laboratory jacket when our class met in the small first-floor workshop beside Parma’s Conservatorio Arrigo Boito. There were ten students the year I studied with him: three Italians, two Japanese, one Korean, one Chinese, one German, one Brazilian and me. Renato was warm and generous, teasing the most confident students, sheltering the shy. He called me ‘l’Americano’ long after he knew my name and recommended that the vegetarian in the class try the Parma speciality pesto di cavallo (horse tartar) from the restaurant next door. There was a lighthearted sense of joy in his work and his teaching, even if teaching his craft was a serious and important business.

Renato Scrollavezza, 1927–2019

Renato Scrollavezza was born on April 14, 1927 in Castelnuovo Fogliani, a farming village halfway between Piacenza and Parma. He was initially self-taught and made his first violin aged 17. Six years later, in 1950, he entered the Cremona Violin Making School under Peter Tatar and graduated in 1954. His very early work was personal but slightly naive; in contrast, his mature work reflected the depth of his artistic ambitions. He was greatly admired and considered to be among the most notable modern Italian makers of the post-war era. He won numerous prizes and medals in international competitions and his instruments were sold widely in Europe, America and Asia. In addition to his making, he taught scores of students at the Parma School of Violin Making.

The Parma school was started in 1929 and its first teachers were Gaetano Sgarabotto and his son Pietro. The school closed in 1938 and remained dormant until 1975, when the president of the Conservatorio Arrigo Boito invited Scrollavezza to reopen it. Originally attached to the conservatory, then moved to a workshop across the street and most recently transferred to an impressive building in the commune of Nocetto, the Parma School has educated scores of makers. I was fortunate to study with Renato at a time when his daughter Elisa and her soon-to-be husband Andrea Zanrè were working and teaching beside him. Elisa and Andrea have continued to teach at the school, furthering Renato’s legacy and advancing the level of Parma violin making and restoration; most recently, they have made significant research into the makers of the Mantua school and Guadagnini.

Renato Scrollavezza with his students in 1995. Jason Price is standing, third from left, just behind Andrea Zanrè; Elisa Scrollavezza is front row, second from left. Photo: Jason Price

Renato was born to a humble family and remained modest even after he had achieved success. His tools were not fancy. He used fine materials efficiently and without waste. We were permitted to bring our own wood. I remember as I carved my first scroll that winter I bisected a worm track with my gouge and exposed a white, still very much alive woodworm. Like most earnest beginners I thought too highly of my first creations and I was disappointed to have my first violin blemished by a flaw and less than enthusiastic about excavating a live worm. But Renato was unphased and told me, ‘fai come i vecchi, vai avanti’ (literally, ‘do like the old ones, keep going’, meaning carry on and patch it, as the old makers would have done).

With Scrollavezza we were encouraged to look beyond the right angles, to pursue ‘una bella linea’, to be artists, not technicians

Renato taught us to use simple hoops of spring steel to glue the top and back of a violin to the ribs and he showed us how to modify clothespins to make lining clamps. At the time I didn’t appreciate the elegance of his spartan efficiency. I saw my friends in the Cremona school using fancy clamps purpose-milled from aluminium and brass. In their first two months at the Cremona school, students learned to plane a block of beech into a cube. With Scrollavezza – for better and worse – we were encouraged to look beyond the right angles, to pursue ‘una bella linea’, to be artists, not technicians. For Renato, part of the violin making process was to position a layer of romance over our work. This approach is controversial; many people expect a violin making school to teach you to use your tools and only after that can you learn to make violins. But 23 years later, having seen the myriad styles and approaches of the violin business, I am still envious of Renato’s romantic and elemental attitude towards his craft.

Renato had a profound sense of himself as part of the continuum of violin makers, but also as an artist and an individual. Among his output were lutes and guitars and ancient instruments no longer of practical or commercial use. His instruments demonstrated flair and creativity and often featured carved heads, decorative inlays, unusual outlines and fanciful soundholes.

His poetic vision of the artist–luthier gave individual identity to each of his creations. Like Sesto Rocchi, he named each of his instruments and wrote the name in ink on their label. The names range from the predictably musical (‘Kreisler’) to the historical (‘Michelangelo’) to the mythological (‘Afrodite’ for a viola d’amore). When I studied with him he was still making instruments but had slowed to a handful per year. In his house just outside Parma in the village of Ronco Campo Canneto he had created a museum and filled it with instruments he made.

Renato’s influence casts a long shadow. He leaves many students and followers, too many to name, all of whom are now mourning the end of an era and the loss of one of the giants of 20th century violin making. Thank you, Maestro, for what you gave us.

Read one of Renato Scrollavezza’s rare interviews, published in 2017.