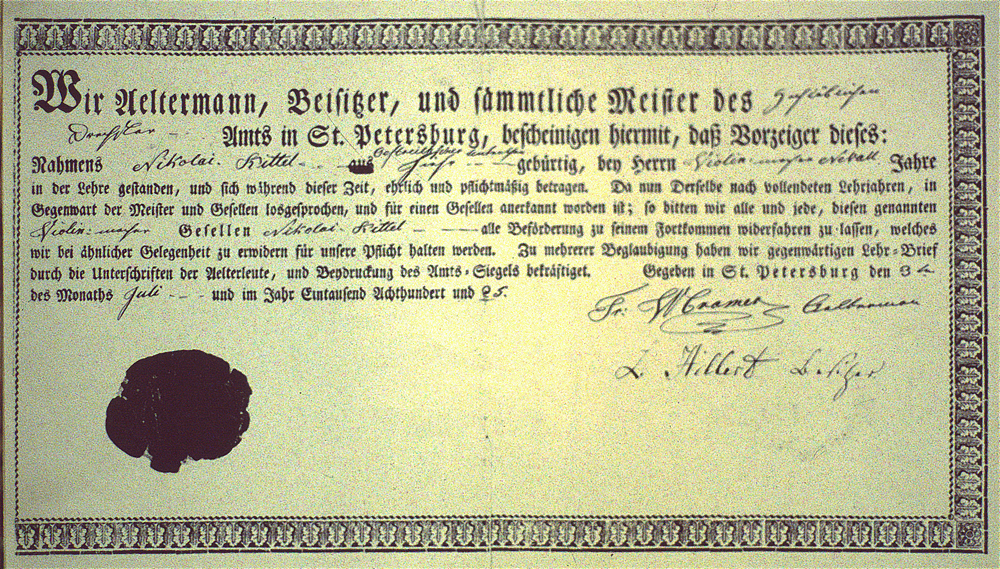

On July 3, 1825 Nikolai Kittel completed his five-year apprenticeship in the St Petersburg workshop of the violin maker Nevall [1], receiving his journeyman certificate. He was now officially a violin maker and was therefore allowed to set up a shop on his own.

Kittel’s advancement came at a critical moment in the history of his native Russia; several months earlier Tsar Alexander I had died and had been succeeded by his brother Nicholas I Pavlovich. Nicholas I’s reign began stormily, when a group of army officers conspired to dethrone him in an uprising known as the Decembrist Revolt, also called the first Russian revolution. Nicholas I brutally suppressed the revolt, having the leaders – mainly intellectuals and young noble officers – executed or deported to Siberia. He ruled the country autocratically for the next 30 years, suppressing social and economic change and concentrating on the expansion of the Russian Empire. As a consequence of his deliberate restriction of the middle class, Russia remained mostly a feudal rural society with a broad mass of poor farmers and serfs and a few very rich nobles.

Nikolai Kittel’s journeyman certificate, which he received in 1825

Nicholas I’s closure to change and outside influence appears to contradict the intentions of Tsar Peter the Great, who had founded the harbor city of St Petersburg in 1703 as a gateway to Europe and modernization. The country’s human and financial resources were concentrated in the development of the city, which was proclaimed the capital of Russia in 1712. The Tsarist court soon became the desired destination of most of the country’s nobles.

The growing wealth of this very European capital soon attracted craftsmen and artists from all over Europe, with a strong contingent from Germanic countries. This important ethnic group within the St Petersburg society had its own German newspaper, formed guilds (as we witness with Kittel’s journeyman certificate) and had its own Lutheran church. The fact that most of the Russian Tsars married German princesses of course strengthened the German influence. The most prominent of those ladies was Sophie von Anhalt-Zerbst, better known as Catherine the Great.

According to the letter of apprenticeship from 1825, written in German and issued by the ‘Wood turner’s Guild of St Petersburg’, Nikolai Kittel had Austrian citizenship but was ‘born here’ – meaning in St Petersburg. From a later document we learn that he was born in 1805 or 06 and baptized as a Catholic. Kittel grew up in St Petersburg’s German community and was well enough connected to apply successfully for the post of the Official Maker of the Imperial Orchestras in 1828. Finally in 1835 he became the official Instrument Maker to the Russian Court – the highest position a violin maker could reach at that time in Russia.

In the same decade that Kittel became self-employed, the Russian-born instrument maker Ivan Andreevich Batov (1768–1839) lived a very different life. Unlike Kittel, who was a free craftsman with a foreign passport, Batov was born a serf and owned by Count Dmitry Nikolaevich Sheremetev. It is recorded that Batov manufactured all kinds of instruments, including violins and cellos and also guitars, harpsichords and clavichords. [2] In 1822 he made a cello for his master that was considered so beautiful that Sheremetev gave him his freedom, together with his entire family. In 1829 he was awarded the Grand Silver Medal for a violin and cello, which were displayed in the first public Industrial Exhibition of Russian products.

This enormous social discrepancy was also to be found among musicians. At the same time that we find free musicians employed in the Imperial Orchestra and well-known soloists from all over Europe paid handsomely to perform concerts in the palaces of the rich, we also find serf orchestras owned by musically interested nobles. It was not unusual for professional musicians and high-ranking noble officers with considerable playing abilities to perform in the same orchestra alongside serf musicians.

‘On sale is a very good musician who plays the viola in instrumental music and the bassoon in brass music; he is also a good footman, of a good height, twenty years old; price 1200 rubles.’

The following newspaper advertisement in the Moskovse Vedomosti from the early 19th century underlines these particular social circumstances: ‘On sale is a very good musician who plays the viola in instrumental music and the bassoon in brass music; he is also a good footman, of a good height, twenty years old; price 1200 rubles.’ Russia was stuck in its feudal system, and the changes introduced by Tsar Alexander II in the second half of the 19th century proved to be too late.

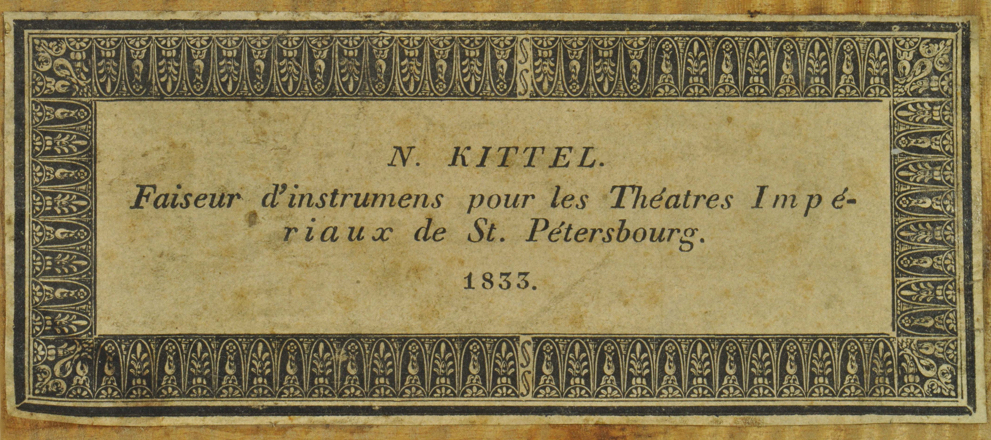

The label of Kittel’s 1833 cello. Photo: Josef Gabriel

Kittel himself established his place in this society and managed a respectable career as a craftsman. The first recorded instrument by Kittel is a cello from 1828. The well-preserved cello displayed here is from 1833, bearing the original label ‘N. Kittel, Faiseur d’instruments pour les Theatres Imperiaux de St. Petersbourg, 1833’, which supports the documentary information about his position at that time. The label is written in French, the common language among the nobles in Russia, as throughout Europe, and a language Kittel appears to have spoken fluently along with German and Russian. [3] The cello’s original pegs have a distinctive double-eye decoration that connects directly to the bows that were to make Kittel famous. These eyes, with a gold circle around an abalone center, have exactly the same proportions as those in the frogs of Kittel’s early bows. Those early bows were obviously inspired by François Xavier Tourte, who was the role model for bow makers across Europe in the 19th century.

The original pegs of the cello have pearl eyes with dimensions that match those of Kittel’s bows. Photo: Josef Gabriel

How Kittel learned the craft of bow making is currently unknown. Certain working methods indicate that he was self taught, using Tourte’s bows as examples. Bow connoisseur Paul Childs presented to me pictures of a Tourte bow that, according to a Hill certificate, was formerly the property of Nikolai Demidov, a noble Russian who was a diplomat in France during the reign of Napoleon I and was presented with this bow as a gift for his services. In 1812 Demidov returned to Russia, where he became a close adviser of the Tsar. On the request of the Tsar this bow was given as a gift from the Demidov family to the Belgian violinist Henri Vieuxtemps.

Judging from the work, one would assume this particular Tourte bow was made after 1812, but the Demidov family continued their close relations to France after this date and traveled there frequently, leaving their mark not only as businessmen and diplomats, but also as connoisseurs of good food, resulting in the ‘Chicken Demidov’ dish. We can speculate that Kittel, as a rising violin maker in St Petersburg, would have seen this bow at Demidov’s early in his career. If not there, he surely saw it through Vieuxtemps. The celebrated Belgian violinist was a frequent traveler to Russia by 1837 and later became a resident of St Petersburg, where he would have been in contact with Kittel. The first chronicler of Russian instrument making, Evgenij Vitachek, remarked in his notes published in 1952 that Vieuxtemps owned seven Kittel bows. [4]

Violin and cello bows by Kittel. Photos: Josef Gabriel

Vieuxtemps’s Russian period is a good example of the life of a successful musician in St Petersburg during the first half of the 19th century. His concerts with the imperial orchestras performing Mozart, Mendelssohn and Beethoven along with many of his own compositions met with applause from the audiences and praise from the critics. He also performed chamber music at soirées with such celebrities of the time as cellists François Servais and Franz Knecht, violinists Ludwig Maurer, Alexei Lvov and Nicolai Yusupov, and his favorite sonata partner, the outstanding pianist Anton Rubinstein. Finally he was appointed the concertmaster of the Imperial Orchestras from 1846 to 1852, with a very comfortable annual salary of 2,300 rubles. [5]

Vieuxtemps also taught wealthy noble amateurs at their homes in St Petersburg. Besides receiving a good income for this work, he was also rewarded with precious gifts, including three Stradivari violins, a cello for his brother and various other high-quality Italian instruments. We can assume that besides the recorded Demidov Tourte, Vieuxtemps also accepted bows made by Kittel as smaller gifts. Bows made for the wealthy nobles for personal use, private collections or donations explain the high percentage of bows with gold and tortoiseshell mountings in Kittel’s output. These bows, desired not only for their precious materials and tasteful execution but also their playability, deserve closer examination.

In Part 2 the authors examine Kittel’s work in more detail.

Klaus Grünke and Josef Gabriel are co-authors of ‘The Bows of Nikolai Kittel’, together with Yung Chin and Andy Lim.

Notes

[1] This is the only known reference to the violin maker Nevall.

[2] Evgenij Vitachek, Essays on the History of Bow Instrument Making, published 1952, E. Bumarek (out of print).

[3] Letters from Kittel to Vuillaume survive, written in French.

[4] Evgenij Vitachek, Essays, op. cit.

[5] Henri Vieuxtemps, Lev Solomonovich Ginzburg, Paganiniana Publications, 1984.