As we saw in part 1, Nikolai Kittel appears to have been self taught, using Tourte as his model. Besides more or less copying Tourte bows, he devised some techniques of his own, most famously in the ‘Parisian double eyes’. These eyes were drilled with one drill bit, shown by the continuous grain in the ebony part of the eyes. His French and German contemporaries used a single cutter to drill out the hole for the entire three-piece eye. The fact that Kittel separately made and fitted his eyes is shown by the end grain in the ebony circle.

Another very typical feature on his gold-mounted frogs are the copper doublings under the flat of the ferrule and the heelplate. The underliner and lower heelplate in one piece, à la Tourte, are always fitted in a mitre joint with the back heelplate. We find as a rule three pins in the lower heelplate and two in the back, changing to three in the later-period bows. As there is no technical reason for three pins in either occasion, some have speculated about a connection with Freemasonry symbolism, but there is no real evidence for this theory.

More important, Kittel’s sticks, made mostly of highest quality pernambuco wood, show modern stick dimensions, with a 73 cm length and proportions and graduations similar to those of Tourte. In the upper part of the sticks behind the head we very often see the grain running out of the stick, which strongly indicates that this part of the stick’s curve was cut out of the board rather than bent. In Kittel’s early period we find mostly octagonal sticks, while later we see more round sticks with a lighter choice of pernambuco combined with a more slender execution. This was to save weight, a development that we find all over Europe from the 1860s as a result of players’ demands for a lighter bow that would suit the period’s changing playing technique. The model of the heads also changes from a more masculine Tourte appearance to a rounder, lighter version. Bows with gold mountings usually have a gold faceplate, though we haven’t seen silver-mounted bows with silver faceplates; here ivory or bone was the general rule.

Kittel was already 35 and well established in society when he married Maria Louisa Tornau in 1841 in the Catholic Church of St Catharina. His wife was Lutheran, but after the third call for dispensation they were finally allowed to marry under the rite of the Holy Catholic Church. One of the witnesses was Staatsrat (Consiliarius Status) Jacob Lepunov, demonstrating Kittel’s excellent connections in society. Two years later their first son, Nikolai Jr., was born, followed by a daughter named Katarina in 1844. The 1840s were probably quite prosperous for Kittel’s workshop, as during this period the city grew to over 400,000 inhabitants and the economic woes of the later 19th century were not yet evident.

Left: Kittel’s marriage certificate from 1841; right: his application for a travel permit dated 1858. Photos: Kenway Lee

The Crimean War from 1854 to 1856 marked a turning point in Russian history. Territorial expansion and the richness of the new territories helped Tsar Nicholas to feed the financial needs of the wealthy by granting luxurious credits for vastly overrated properties. This system ended abruptly with the loss of the Crimean War. Tsar Nicholas had died in the middle of the war and his son and successor Alexander II therefore started his reign with the burden of a lost war. Nevertheless, the modern-educated Alexander began a long-overdue transformation of Russian society into a modern state. He made structural changes in his administration, including the military and justice, which resulted in a more open society with emerging civil rights. Another major step was the liberation of the serfs in 1862. However, all these changes came too late. They were both challenged by the elite and considered as not going far enough by a growing opposition. Alexander II survived three assassination attempts but the fourth proved successful.

Prince Nikolai Yusupov… describes Kittel as a ‘capable and conscientious craftsman’

Kittel surely felt the economic downturn to a certain degree, together with increased competition from imported instruments and bows of high quality. Prince Nikolai Yusupov mentions in his 1856 book Luthomonographie that the bows by ‘Bausch in Leipzick’ are especially desired; he also describes Kittel as a ‘capable and conscientious craftsman’. We see many more silver-mounted bows bearing the Kittel workshop brand from the later 1850s and the 1860s in contrast to his earlier period.

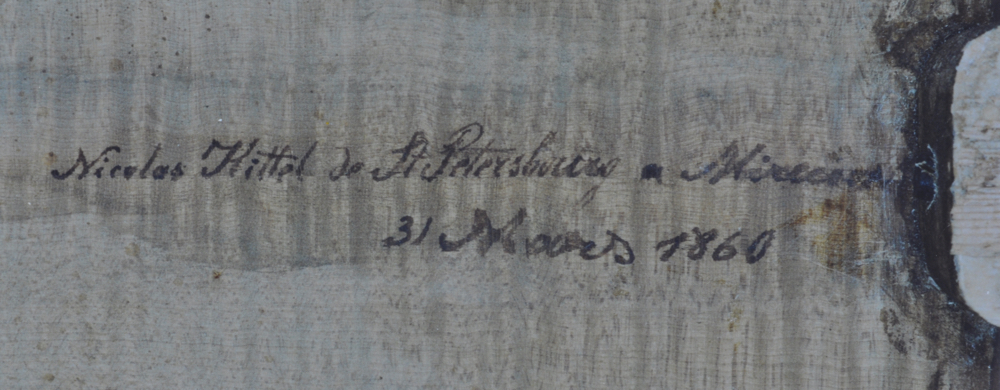

On the other hand, Kittel took advantage of the new freedoms introduced by Alexander II. We are lucky to have a surviving document in which he requests a traveling permit for himself and his son in 1858. A year later he traveled via Germany to France to revitalize his business connections and left his son with Honore Derazey in Mirecourt to study French techniques. A violin obviously from the Derazey workshop bears the handwritten inscription, ‘fait par Nicolas Kittel de St. Petersburg a Mirecourt 1860’, a nice piece of proof supporting the documentary evidence for this trip.

The inscription inside a Nikolai Kittel Jr. violin made during his visit to Mirecourt, 1860

Nikolai Kittel Jr. returned the same year to St Petersburg, where he supported his father in the family workshop. In the previous year the Russian Music Society had been founded by Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna and Anton Rubinstein, concentrating on the education of Russian musicians and composers. This society led to the inauguration of the first Russian music conservatory in 1862 with Rubinstein serving as the first director. The initial staff member for violin was Henryk Wieniawski, who had arrived in St Peterburg in 1860. Heading the cello class was Carl Schubert, who was succeeded after his unexpected death in 1863 by the Latvian Karl Davidov. Musical life in the city was vital and growing in the 1860s, with plenty of demand for instruments, bows and accessories. Kittel’s business was in full bloom when his wife died unexpectedly in 1865. From this time on, according to comments from the family, he became somber and more or less stopped working. He died a few years later, on April 14, 1868.

Violin made by Nikolai Kittel Jr. in Mirecourt, 1860. Photos: Benjamin Schröder

More photos

Nikolai Kittel Jr. continued the family business, making and trading instruments and bows. Here the fruitful connection to the outstanding German bow maker Heinrich Knopf (1839–1875) has to be mentioned. The sheer number of Knopf bows bearing the original Kittel brand suggests that this connection started before 1868. These bows were obviously made according a very specific given model. This is especially evident in the frogs, which appear in many technical aspects very similar to ones from St Petersburg. The heads, even though slightly different in style, clearly show Knopf’s authorship. Knopf crafted only bows of the highest quality and choice wood for the Kittel shop, which indicates a very substantial business connection. The bows were sent unbranded and were then approved and stamped in the Kittel shop. Nevertheless, at the same time we have Kittel bows made in St Petersburg marked with the same brand with the typical bowl on top of the initial ‘K’. In his notes on Kittel, Vitachek mentions the name of the bow maker Ivanov, who supposedly worked in the Kittel shop in the later years. But because we have no surviving bows with Ivanov’s personal brand, we have no reference for his hand in the output of the late Kittel workshop in St Petersburg.

Knopf crafted only bows of the highest quality and choice wood for the Kittel shop, which indicates a very substantial business connection

Nikolai Kittel Jr. continued doing business on the corner of Michael Street and Nevsky Prospekt until 1873, when he sold the desirable and prominently located property to an investment group. The old workshop was replaced by the famous Grand Hotel d’Europe, which opened its doors in 1875 and is still considered the number one address in St Petersburg today.

In 1868, the same year that Kittel Sr. died, the Austro-Hungarian Leopold Auer arrived in St Petersburg, taking over the violin department from Wieniawski. During the following 49 years his teaching at the conservatory created some best violinists of the early 20th century, including Misha Elman, Nathan Milstein, Efrem Zimbalist and Jascha Heifetz. The fact that these soloists all played Kittel bows helped to make his work famous around the world.

With thanks to Yung Chin for our common intensive and exciting study defining the typical features and working techniques to be found on Kittel bows. We are equally grateful to Andy Lim for his thorough research on the musical background of 18th- and 19th-century St Petersburg and for Russ Rymer’s careful editing. Special gratitude to Kenway Lee, an enthusiastic Kittel researcher and admirer of his bows, who died unexpectedly in May 2013. His findings, which he left us so graciously, are the backbone in understanding Kittel’s life. We also thank the staff of the Glinka Museum in Moscow for their kind cooperation, which may lead in time to an addendum to our book.

Klaus Grünke and Josef Gabriel are co-authors of ‘The Bows of Nikolai Kittel’, together with Yung Chin and Andy Lim.