Count Cozio, whose agent Carli was in regular contact with Luigi Tarisio

As we saw in part 1, the ‘Messie’ Stradivari violin appears to have passed from the collection of Count Cozio to that of Luigi Tarisio at some point in the 1820s. It is not until 1839, however, that there is any hard evidence of communication between the two Piedmontese collectors, possibly related to the fact that several sources indicate that Tarisio himself was illiterate.

In the earliest contemporary record of Tarisio’s activities, on December 2, 1839, Cozio received a letter from his agent Carli, informing him that Tarisio had requested a chance to view the Count’s instruments in Milan, which Carli had granted. [1] He adds that Tarisio wants to make ‘new deals’ with Cozio, implying that there had been deals made previously; one presumably being the purchase of the ‘Messie’. Cozio died in 1840, and the contract was subsequently made between Tarisio and Cozio’s daughter Matilde, with Carli as the agent. Tarisio succeeded in negotiating for 13 violins by ‘various makers’, a 1746 Bergonzi cello (still untraced), three old necks and an old violin top, for a total of 2,850 francs, well below Cozio’s original asking price of 4,900 francs, [2] some evidence of Tarisio’s business acumen. The instruments are subsequently identified in the accounts sent to Matilde by Carli as a Pietro Guarneri of 1772 (sic), a Giuseppe Guarneri of 1707, two Carlo Bergonzi violins dated 1733 (now identified as the ‘Kreisler’ and the ‘Salabue’), a violin by ‘A. Sneider’ with a label of Amati, a Francesco Rugeri, a Cappa, six Guadagninis (probably made for the Count by Guadagnini) and the enigmatic Bergonzi cello of 1746.

Tarisio made further approaches to Matilde through Carli in 1842 and 1844. On September 3, 1842 Carli reported that Tarisio had tried to buy some Guadagnini instruments from the collection, but the offer of 100 francs was insufficient. [3] On January 27, 1844, [4] however, he revealed that Tarisio had bought six Guadagninis, and in June of that year [5] made an offer for two Stradivaris remaining in the collection, which was declined. (Count Cozio had made a contract with G.B. Guadagnini in Turin for the exclusive rights to all the instruments he made between 1773 to 1777, which resulted in some 50 or so violins, violas and cellos.)

Cozio received a letter from his agent Carli, informing him that Tarisio had requested a chance to view the Count’s instruments in Milan

Paolo Lombardini’s Notes on the Famous Cremonese School of Stringed Instrument Making, published in 1872/3 is a very useful source in which we learn that from 1840 to 1852 Tarisio was scouring Cremona and its district, accompanied by a local violinist named L. Faja. He had another aide, Leone Fuchs, an amateur violist and owner of a coffee shop in Brescia, who served as his intermediary. Between them these three men found 20 violins in this period, including several Amatis, three Stradivaris and the odd ‘del Gesù’ and Bergonzi. On a last trip to the city in 1852 Tarisio bought another 30 violins from the violin maker Enrico Ceruti (although Elia Santoro in his 1973 publication Traffici e falsificazione dei Violini di Antonio Stradivari has it that Ceruti bought 30 instruments from Tarisio).

By contrast, after Tarisio’s death, in 1859 Fuchs and ‘a one legged French client’ bought several more violins in Cremona, but could find no Strads. Fuchs continued to act as a dealer on his own account up until 1872 at least, when he bought 79 instruments, but all in a very poor state of repair. Lombardini concludes that Tarisio had effectively done Cremona a great disservice in depriving the city of its best instruments. [6]

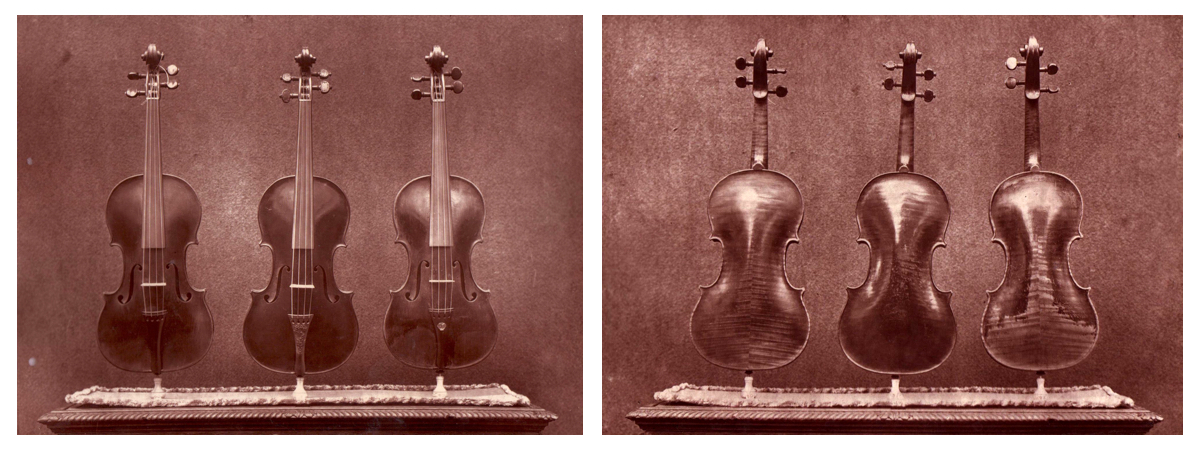

The ‘Kreisler’ Bergonzi – one of the instruments that Luigi Tarisio bought from Count Cozio. Photos courtesy of Dextra Musica, photographer: Richard Valencia

More photosBy 1848 Tarisio had expanded his contacts to London and was in touch with John Hart (1805–1874), then the leading English dealer. In that year Hart bought from Tarisio the small-sized Stradivari of 1720 that he sold to the collector Joseph Gillot, whose name is still attached to the violin. Other dealings with Hart brought Tarisio to another distinguished English collector, James Goding, whom he visited in 1851. Hart tells the story that Goding was amazed by Tarisio’s ability to identify every instrument in his salon, not knowing that they had all been acquired through him. [7]

Tarisio’s presence in England prompted most of the written anecdotes about his personality and working methods. This enigmatic character must have appeared to have come straight out of a Dickens novel to London’s literari. Among them was Charles Reade, a novelist and violin connoisseur who was clearly drawn to Tarisio. In a period invigorated by the Gothic styles of Horace Walpole and Mary Shelley and the romantic poets, he must have seen in Tarisio a perfect subject: an unlettered wandering violin fancier; an almost supernaturally able diviner; a magician of Stradivaris. When it suited him he would present himself as fashionably dressed and mannered; at other times down at heel and road-worn. He might have stepped straight from a gothic novel or a fairytale himself. Reade’s passing description of him as ‘an ephemeral insect’ provokes a dark shudder. [8] ‘He had gems by him no money would buy… The man’s whole soul was in fiddles,’ he wrote, a suggestion of a Faustian pact behind Goding’s remark to John Hart that ‘that man smells a fiddle as the devil smells a lost soul’. [9]

It was an age in which writing about the violin was starting to flourish and dealers were coming to see the advantage in publishing their credentials as authorities on the subject. Nicolas Lupot collaborated with Abbe Sibire in producing the first serious work in this genre, La Chelonomie, ou le Parfait Luthier in 1806. François Joseph Fétis published his biography of Stradivari under the guidance of J.B. Vuillaume in 1856, and in London in 1875, George (the son of John) Hart wrote The Violin: Its Famous Makers and their Imitators, which is the origin of most of the well-known anecdotes and assumed facts about Luigi Tarisio.

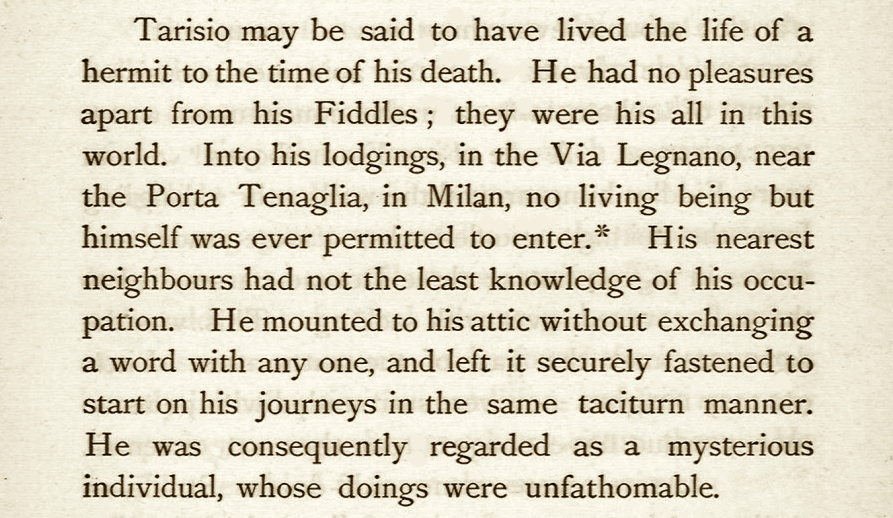

An excerpt from ‘The Violin: Its Famous Makers and their Imitators’ by George Hart, 1875

Charles Reade first published his observations in the Pall Mall Gazette in 1872, and a collected edition of his essays, Readiana, was issued in 1882. Reade was a popular author in his time and his reputation survived long enough for George Orwell to write in one of my own favourite gems of criticism, that he had ‘the charm of useless knowledge… crammed into books which would at any rate pass as novels’. Several popular books about the violin followed, including the Rev. H.R. Haweis’ Old Violins and Violin Lore (1898) and Franz Farga’s Geigen und Geiger (1930) reiterating and expanding the stories of Reade and Hart. In 1957 William Silverman published a novelised version of Tarisio’s adventures, The Violin Hunter, in itself more of a fairytale than a dramatic story. [10] It is these accounts rather than any serious historical research that still provide the basis for our present romanticized understanding of Tarisio.

They tell us among other things that Tarisio had a deep and passionate regard for the instruments he collected, often reluctant to sell them and eager to reclaim them when the opportunity arose. The story of the ‘Spanish Bass’ was manna to Reade’s imagination and remains probably the best-known story, which Reade tells with enthusiasm. The facts as far as can be discovered are that this 1713 Stradivari cello was retrieved from Spain bit by bit. Tarisio first spotted the table in the Paris shop of Georges Chanot, who had found it in the shop of Silverio Ortega in Madrid. Tarisio bought the table from Chanot and immediately set off for Spain to recover the rest of the cello. Ortega directed him to an elderly widow (in some sources ‘a lady of rank’) for whom he had made a new top to replace the damaged original. Tarisio was able to negotiate the purchase of the Stradivari from the lady and returned with it to Paris, where the pieces of the cello were reunited by Vuillaume. Reade relates Tarisio’s ghastly storm-tossed voyage back across the Bay of Biscay with the precious instrument, ‘the ship rolled; Tarisio clasped his bass tight and trembled. It was a terrible gale… Ah my poor Mr Reade, the bass of Spain was all but lost,’ he apparently told the author. [11]

‘Tarisio was found lying on a tattered sofa fully dressed clasping two violins to his chest as if in a spasm’

Hart’s book provides the dramatic account of Tarisio’s demise, which came about in the winter of 1854 in Milan. ‘One night,’ he relates, ‘he had been seen climbing up to his attic. Then he remained invisible for two days… local officials were sent to force open the door. Tarisio was found lying on a tattered sofa fully dressed clasping two violins to his chest as if in a spasm.’ Hart describes a sparsely furnished room with a bench and some tools, stuffed full with violins including six by Stradivari, violas, cellos and a Gaspar ‘da Salo’ double bass. [12]

In Paris, J.B. Vuillaume heard the news and immediately made preparations to travel to Italy. He amassed as much cash as he could and made for Fontaneto, where he arrived in January 1855. According to Hart, he found Tarisio’s family in a bare, low-roofed farmhouse sitting around a blackened cauldron, another scene which could have been borrowed from gothic fiction. He found six instruments on the farm: Guadagninis, a Bergonzi, a ‘del Gesù’ and two Stradivaris, one of which was the ‘Messie’. The Hills’ informant, M. van der Heyden, told them that the ‘Messie’ and the ‘del Gesù’ (the ‘Alard’ of 1742) were both in the bottom drawer of a ‘rickety piece of furniture, which Vuillaume had great difficulty opening. [13] The next day he set out for the apartment in Milan, where he found another 144 master instruments. Tarisio’s family happily accepted 80,000 francs for the lot. In Hart’s opinion, the haul was worth no less than two million francs. Clerks also found large amounts of cash in notes and gold coins stuffed into a mattress.

The ‘Messie’ (centre) with ‘La Pucelle’ (left) and ‘Le Violon du Diable’ (right), from the exhibitor’s edition of the Catalogue of the Exhibition of Ancient Musical Instruments at the South Kensington Museum, 1872. Images courtesy Ben Hebbert

This single purchase was the making of Vuillaume’s reputation in Paris. As the new owner of the ‘Messie’, he supervised its display at the 1872 Great Exhibition in London. But through Reade and Hart, Tarisio’s fame was also entering the public imagination.

Even without the accumulated layers of mythology, in real terms Tarisio leaves in the historical record 20-odd Strads, half a dozen ‘del Gesù’ and many other instruments whose provenance begins simply with his name. He left no record of where he found them or from whom they were acquired. Only in a few cases, such as the ‘Messie’ and the ‘Spanish Bass’, do we know something of their earlier history. Nor do we know what he physically did with the instruments he collected. We know he was a woodworker by training and Hart tells us that his Milan attic contained a workbench and tools. A good deal of his education in fine instruments stemmed from an interest in labels, which he collected, as did Count Cozio, as others would collect stamps. How far he allowed himself to tinker with his treasures may never be known, and the status of an ‘original label’ can never be taken fully for granted. The Hills were certainly of the opinion that he raised lesser instruments into greater ones and possibly was originally responsible for the renaming of Gofriller cellos as Bergonzis, an error that became common in the 19th century.

Tarisio leaves in the historical record 20-odd Strads, half a dozen ‘del Gesù’ and many other instruments whose provenance begins simply with his name

By the time the Hills were writing in the early 20th century, the process begun by Tarisio of relieving Italy of its gems of lutherie had long been underway; Cremonese violins were prized in courts and aristocratic homes throughout Europe and now new markets were being found among professional players and wealthy businessmen. Indeed the Hills lamented that London in turn was losing its share of these masterpieces in the wake of the First World War and the growing economic power of America.

Tarisio was undisputably obsessed with the violin, a devoted admirer and collector of the works of the great masters. How much he might be judged today as a sharp dealer would inevitably be unfair. Count Cozio had the same attitudes; he would not hesitate to ‘improve’ an instrument with a better label if he thought that it was appropriate and nor would any of the dealers and repairers through to modern times. The evidence is powerful that Tariso did not see financial gain as his sole ambition. He needed money to get more and better instruments, not to furnish a palace. The violin was his life-long controlling passion.

Makers, restorers and experts John Dilworth and Carlo Chiesa are particularly known for their writings about fine violins. They co-authored ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ among other books.

Notes

[1] Cozio di Salabue, Memoirs of a Violin Collector, Trans. Brandon Frazier, 2007, p.179 & 182; Duane Rosengard, Giovanni Battista Guadagnini, Carteggiomedia, 2000, pp. 156–157.

[2] Cozio di Salabue, Memoirs of a Violin Collector, Op, cit. p.179 & 182.

[3] Cozio di Salabue, Memoirs of a Violin Collector, Op. cit. pp 185–186.

[4] Cozio di Salabue, Memoirs of a Violin Collector, Op. cit. pp 188–189.

[5] Cozio di Salabue, Memoirs of a Violin Collector, Op. cit. p. 90.

[6] Paolo Lombardini, Antonio Stradivari e la celebre Scuola cremonese, Cremona Dalla Noce, 1872/3.

[7] George Hart, The Violin: Its Famous Makers and Their Imitators, Dulau, London, 1885.

[8] Charles Reade, Pall Mall Gazette, 1872.

[9] George Hart, Op. cit.

[10] William Silverman, The Violin Hunter, John Day Co., New York, 1957.

[11] Charles Reade, Op. cit.

[12] George Hart, Op. cit.

[13] W.H. Hill, A.F. Hill, A.E. Hill, Antonio Stradivari, his Life and Work, W.E. Hill, London, 1902, p.263.

Additional sources

Roger Millant, J.B. Vuillaume Sa vie et son oeuvre, W.E. Hill, London, 1972.

Giovanni Accornero, Ivan Epicoco, Eraldo Guerci, Il Conte Cozio di Salabue: Liuteria e Collezionismo in Piemonte, Edizioni Il Salabue, 2005.

Christopher Reuning (ed), Carlo Bergonzi, A Cremonese Master Unveiled, Fondazione Antonio Stradivari, 2010.