The friendship between Jacqueline du Pré and Charles Beare dated from 1963, when both were beginning to make their mark in the music world – Beare as a leading expert on antique violins and du Pré as one of the finest English cellists of her generation.

‘I got to know her socially as we lived quite near each other, and we became friends,’ he recalls. ‘I was overwhelmed by her on all fronts. She was a terrific girl – very energetic but very sensible.’

At the time, du Pré was playing an early Strad. ‘It was dated 1673, but it might have been a bit later. It was quite a big cello and had a big, full sound, but to her it didn’t have the warmth of a golden period Strad.’

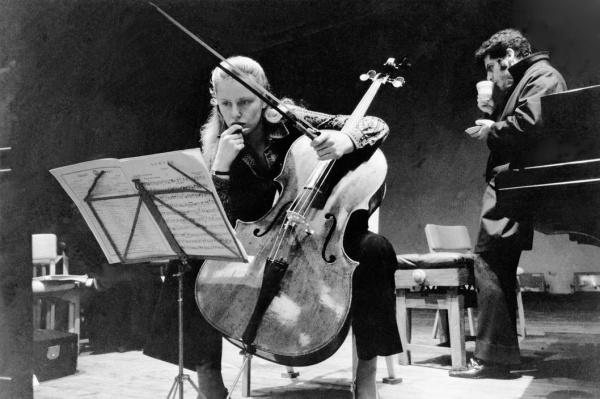

Du Pré recording Elgar’s Cello Concerto with Barbirolli at Kingsway Hall in London, 1965. She used the ‘Davidoff’ for this classic recording. Photo: EMI Classics

The initiative to find a replacement came from du Pré’s benefactor, her godmother Isména Holland, late in 1964. ‘Her career was not yet at its peak and her benefactor wanted her to have the very best. So Jackie came and asked me to look for something.’

Beare knew that the 1712 ‘Davidoff’ Stradivari was with the Wurlitzer firm, where he had trained in the early 1960s, so he phoned Mrs Wurlitzer, who brought the cello to London personally. He was one of those assembled when du Pré first tried the ‘Davidoff’, as was her teacher William Pleeth. After du Pré had played for around 20 minutes Pleeth described it as ‘absolutely the perfect cello. He said, “Whether or not it will suit you, you’ll have to find out, but it’s a wonderful instrument.”’ According to Beare, du Pré herself was ‘overwhelmed by what it could do. It was wonderful – and still is!’

After du Pré had played the ‘Davidoff’ for around 20 minutes, Pleeth described it as ‘absolutely the perfect cello’

So the ‘Davidoff’ was bought for du Pré, who a few months afterwards used it for her classic Elgar Cello Concerto recording of 1965 with Sir John Barbirolli and the London Symphony Orchestra.

The ‘Davidoff’ accompanied du Pré all over the world as her fame grew. ‘She loved it dearly,’ says Beare, but there were two problems. ‘Being a Strad, it wouldn’t willingly take the pressure that she instinctively wanted to apply to an instrument. She really could turn it on with her bow and if you press too hard with an instrument like that you can sometimes come out of the other side of the optimum sound. She was a very strong person and she needed a very strong cello. In retrospect I think a Montagnana would have been perfect for her, but there weren’t any around at that time.’

The ‘Davidoff’ also struggled with rapid changes of climate. ‘We used to have to overhaul it when she came back from her trips. The bridge would be too high or too low and the seams would be open and so on. We didn’t really understand about the atmospheric effects on instruments then and she was traveling all over the place. But give it a couple of weeks in England and it was 100% amazing again.’

Then one morning in 1967 du Pré rang up fresh from an overseas trip to ask if she could borrow another cello to take to Milan that afternoon. ‘She said, “I’ve only just got back with the ‘Davidoff’ and it’s not functioning properly.” So we lent her a Francesco Goffriller and she came back and said “I love it! It’s not the ‘Davidoff’ sound with all its colors but it takes the pressure and it’s survived a tough trip.” She continued to borrow it and a few years later asked to buy it.’

By that time du Pré was married to the pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim and this appears to have influenced her final choice of instrument. ‘Daniel had a problem listening to the “Davidoff” when he was playing with her because the sound in all its glory went out across the hall and, as he was sitting behind her, he couldn’t hear it properly. The Goffriller had a spread of sound, although it didn’t have the same quality as the Strad, and he could hear that better.’

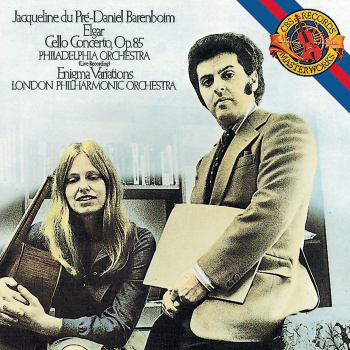

Du Pré with her Francesco Goffriller cello, which features in her 1970 Beethoven trios recording with Daniel Barenboim and Pinchas Zukerman

This was the situation when the couple met the Italian maker Sergio Peresson, who offered to make du Pré a cello. Dated 1970, this cello became her chief concert instrument until her career was cut short by multiple sclerosis in 1973.

‘I heard it on occasion and it didn’t have any colors at all, but it was very loud close to and certainly Daniel could hear it,’ says Beare. ‘I remember her playing the Tchaikovsky Trio in the Royal Festival Hall and I was not as happy as before, and nor were other people who were listening for colors. But by that time she was starting to get quite ill and because Daniel was thrilled to bits with the Peresson no one said anything. That cello did the last live Elgar recording with Daniel and it worked very well for that.’

Du Pré’s Sergio Peresson cello can be heard on this live recording of the Elgar with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Listen to an excerpt from the opening movement below

Du Pré did not demand a lot of adjustments for her instruments. ‘It was often up to me to say I thought something wasn’t quite right, rather than her complaining about the sound. She was completely unfazed by anything really – she was Jackie and that’s the way she played. I remember vividly her way of trying out a cello was to play a note fairly low down on the D string. She played that note for two or three minutes, and you wouldn’t believe the variety of sound and volume and beauty she could get out of it.’

Du Pré’s bows

Beare also looked after du Pré’s bows. ‘She used to come back from her trips with about a tenth of the bow hairs still left,’ he remembers. She preferred strong, heavy bows and used a John Dodd weighing around 90 grams. This lasted until one time when her mother brought it to the Beare shop for a rehair and the car door blew shut on it, breaking it beyond repair. Beare then lent her a Louis Panormo bow, which turned out to be an ideal replacement.

‘Jackie just loved that Panormo. Panormos tend to be heavier than the French bows, and that’s what she liked because she was so strong. She used one of those rubber tubes on it and that particular bow with the rubber was 104 grams, which is overdoing it really! But it was just right for her. If you see her playing in the Barenboim studio recording of the Elgar Concerto in 1967, which Christopher Nupen filmed, you wouldn’t believe the bow could be that heavy because her right hand was so sensitive as well as so strong.’

‘Panormos tend to be heavier than the French bows, and that’s what she liked because she was so strong’

Beare used to visit du Pré after each of her overseas trips. ‘Any time Jackie used to come back from somewhere I used to have an omelette or something in her flat and then cart off the “Davidoff”. She was a wonderful person to be with – she was always such fun.’

He also recalls a time when his phone rang at 3am and ‘a voice announced, “It’s Jackie!” We chatted for a few minutes and then I asked “Where are you?” and she said “Los Angeles”, so I said “You know it’s the middle of the night here?” and she said “Oh golly! I thought it was lunch time!” I can’t remember what the problem was that time but there were all kinds of moments when something happened and she felt like ringing someone back at home.’

When asked about du Pré’s legacy, Beare says simply, ‘She was the most amazing person and the most amazing cellist. I think she was truly an inspiration to everyone.’