Giulio Ettore Degani was born on September 15, 1875 into an Italian dynasty of violin makers and artists. He was initially trained as a violinist and became a professional musician and teacher as well as a violin maker.

Giulio was the grandson of Domenico Degani (1820–1887) and the son of Eugenio Degani (1842–1901), who is today considered the founder of the modern Venetian school of violin making. In 1867 the family had moved to Montagnana, where Giulio and his siblings (Rosina, Marina and Melia) were born. During this period his father Eugenio became a maker of global reputation, winning 15 medals internationally. After Domenico Degani’s death in 1888, Eugenio and his family moved to Venice.

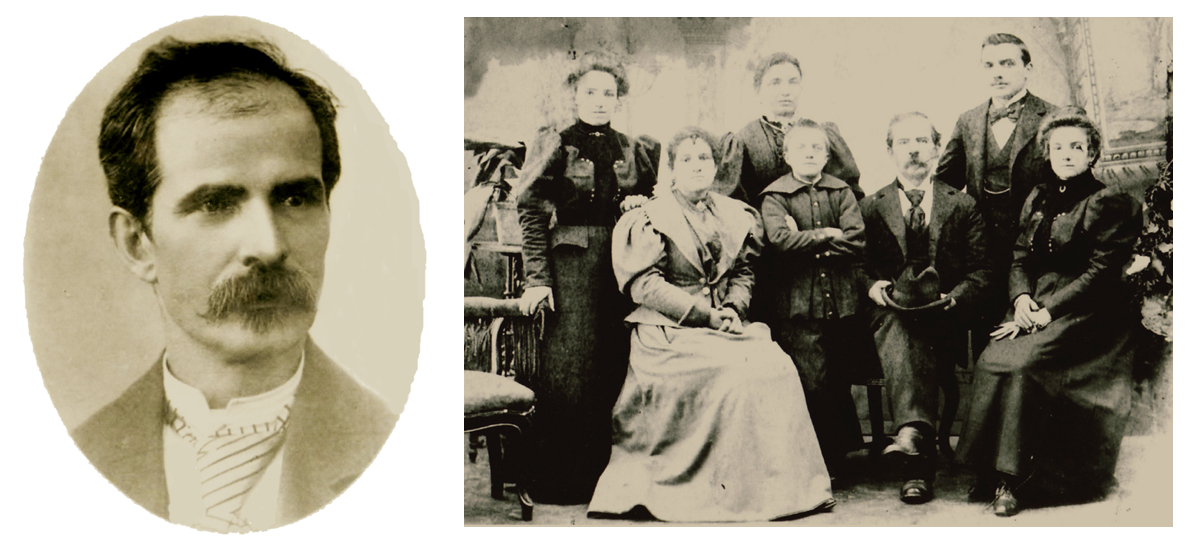

Eugenio Degani (left) and Giulio Degani (right, center) with his family in the 1890s

Giulio started his apprenticeship at a young age. By 1894 he had participated in the Milan Exhibition, winning a ‘premiato con gran diploma d’onore’ along with his father. Some time later, this winning instrument was described as ‘impeccable with a soft varnish of golden brown colour. The tone possessed extraordinary beauty, superb resonance and depth.’ [1]

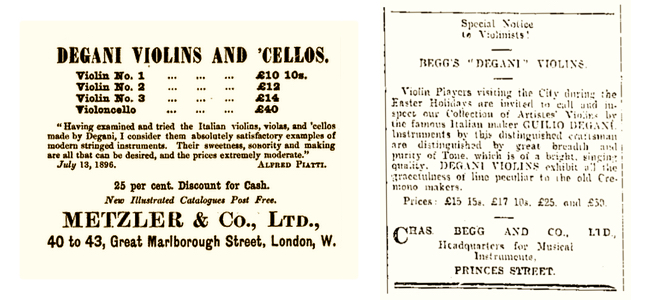

By 1898 the Degani atelier had become ‘Degani e figlio’ and after Eugenio’s death in 1901 Giulio took over running the shop. He won prizes at competitions in Turin in 1898 and Milan in 1906, as well as silver and gold medals at the New Zealand International Exhibition in Christchurch 1906–07 and a gold at Turin in 1911. He developed an international reputation and sold instruments abroad, especially to the UK and US. From the late 1890s his instruments were sold in various shops in England such as Metzler & Co., where they were endorsed by the cellist Alfred Piatti. One advert for his violins by a London shop described them as ‘distinguished by the great breadth and purity of Tone, which is of a bright, singing quality.’ [2]

Early adverts for Degani’s instruments, including an endorsement from the cellist Piatti

As World War I raged across Europe, Giulio Degani received an invitation to work for the Wurlitzer firm in New York and on October 5, 1915 he set sail from Genoa with his friend and protégé Jago Peternella, who was 11 years his junior. They arrived at Ellis Island on October 19. [3] In Degani’s declaration he was described as a ‘Merchant Trader’ and stated his final destination as New York City. As a diabetic, he was not eligible to join up to fight in the war and this condition also explains a lot about his work later in his life.

Giulio Degani (left) in his workshop at Campo San Marziale, Venice, c. 1912–1914 and (right) as a young man in the late 19th century

In New York Degani settled at 15 Christopher Street, not far away from Little Italy, and worked for Wurlitzer’s from the end of 1915 to 1917. In January 1917 Albert F. Moglie (1890–1988), a violin maker and restorer from Rome who had been brought to America in 1914 by Rudolf Wurlitzer to take charge of the restoration department in Wurlitzer’s Cincinnati branch, was transferred to the firm’s New York branch. Whether it was the arrival of Moglie, a younger and highly talented restorer, that prompted Degani’s departure is uncertain, but we know that he decided to leave Wurlitzer’s shortly afterwards. According to personal accounts, Degani was ‘not easy’ socially. He also barely spoke English and later admitted in a letter to his nephew, Giulio Vaccari: ‘to live in USA is very tough, specifically for me that I’m not able to speak English.’ [4]

‘To live in USA is very tough, specifically for me that I’m not able to speak English’

According to the Wurlitzer records, Degani transferred to the Cincinnati branch [5] but on his way there he stopped in Atlantic City, where for a year he lived in a house owned by his friend Frank Coviello, a violinist and fellow Italian; during the same period Peternella was also boarding with Coviello. Degani is listed in the Atlantic City Directory 1917–18 as a violin maker. He supplemented his income by teaching violin and, according to the same letter to his nephew, successfully auditioned for the local orchestra: ‘Some professors suggested me to study to win an audition to play in the orchestra so I studied for seven hours by day and I won.’ [6]

In October 1918 Degani took up his post in Wurlitzer’s Cincinnati branch. He settled at 2232 Boone Street and apparently encouraged his family back in Italy to emigrate. In December 1920 his nephew and niece, Gino and Amelia Bellini (the children of his sister Marina), sailed to join him in Cincinnati.

The following year Degani left the Wurlitzer Co. and moved to a larger house a few blocks from the Ohio River at 2164 Florence Avenue, where he opened his own shop. In the 1922 Cincinnati Directory both he and James Reynolds Carlisle (known at that time as the ‘Stradivari of Kentucky’ and who had also been employed by Wurlitzer) were listed as independent violin makers. Some previous accounts of Degani’s life have suggested that he found himself isolated in Cincinnati among violin makers of largely Germanic origin, but in fact the census records of the time show that his neighborhood was a melting pot of nationalities that included Italian, Russian, German and English immigrants.

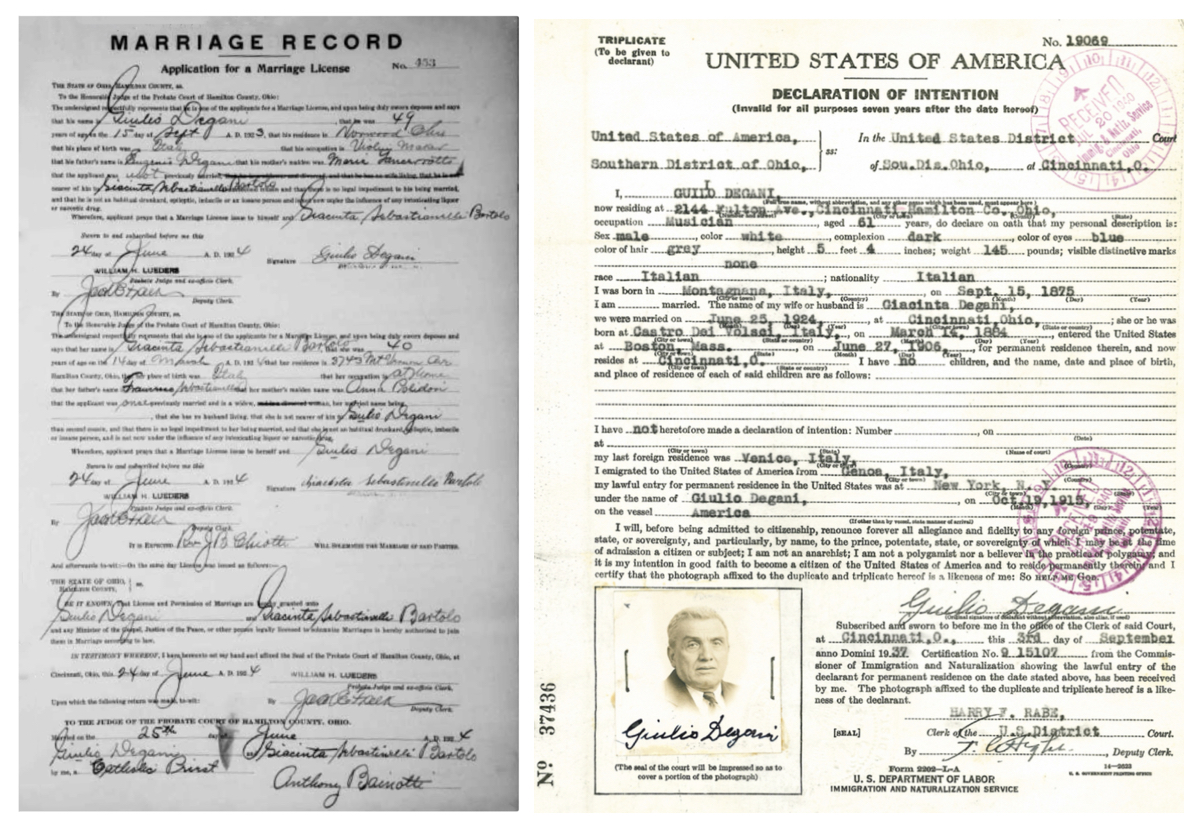

Degani’s marriage certificate from 1924 (left) and his declaration of intent for naturalization dated 1937

During this period Gino Bellini, despite being an artist and lithographer by trade, appears to have helped his uncle in his workshop: in 1921–22 he is listed as a violin maker in the Cincinnati Directory at Degani’s address. After a few years Degani and his niece Amelia briefly resettled in Norwood (now part of greater Cincinnati), where Amelia met Salvatore Buglione. By this time Degani was living with a widow, Giaccinta Sebastianelli Bartolo. Both couples decided to get married on the same day, June 25, 1924, and all four subsequently lived at the same house. In 1925 Amelia gave birth to her first child, Maria, and by 1926 Giulio had moved his growing family to 2144 Fulton Avenue, where the Buglione and Degani families continued to reside together. The following year Amelia gave birth to a son, John, but tragedy struck in early 1929 when Amelia contracted influenza and died soon afterwards, on January 13.

In October of the same year came the worst stock market crash in US history. For immigrants like Degani, their dreams of finding a more prosperous life in America came to a halt. Despite this and the recent family tragedy, Degani continued to produce instruments during this period, including several violins and a cello. According to the US Census of 1930, he already owned his home, which was worth $8,000. But as the Great Depression set in, hardship increased. The Cincinnati Symphony reduced its 1933–34 season to 16 pairs of concerts and introduced salary cuts of one-third for the whole orchestra, while Ohio’s unemployment rate reached 37.3% in 1932. By the end of 1933 Degani had decided to move back to Atlantic City, where opportunities for musicians were more abundant; another factor in his decision may have been the presence of Peternella, who had returned to Atlantic City around 1930 (see our previous feature on Peternella).

In October 1929 came the worst stock market crash in US history. Despite this and the recent family tragedy, Degani continued to produce instruments

Degani opened a shop at 110 South Texas Avenue in the house of a musician friend, Giovanni Musa. The US Census confirms he was still in Atlantic City in 1935 working as a violin maker and violin teacher. Peternella meanwhile had moved to New York in 1932 and, according to Degani’s step-daughter, Lena LaPille Campanella, he invited Degani to work in his shop at 104 West 52nd Street on the corner of 6th Avenue for a brief partnership that seems to have lasted from 1936 to 1937. [7] This was indeed a tough period financially as the US economy took another sharp downturn in mid 1937, which lasted through most of 1938; meanwhile severe drought led to the Dust Bowl of the 1930s in the center of the country. In addition, in early 1937 the Ohio River Flood caused $500 million of damage across the state, with river levels reaching 24 metres in Cincinnati (the highest recorded in the city’s history). Perhaps this prompted the return of Degani, whose wife Giaccinta had remained in Cincinnati during his period in New York, as by the fall of 1937 he is recorded as back at his Fulton Avenue address. [8]

The outbreak of World War II formally ended the years of depression, as millions of men and women went to work for the war effort. Degani joined the Baldwin Factory in the Walnut Hills area of Cincinnati to build wings of airplanes. After the war he worked as a farmer for a Mr Lianisi in Ohio, all the while maintaining his violin shop part time. This explains the scarcity of instruments by him during this decade. Nevertheless, as a maker Degani appears to have been popular with players from the Cincinnati Symphony and he made a fine double bass for Louis Winsel, the principal bass, which is now owned by Paul Robinson. He received his US citizenship on April 29, 1941 and his annual reported income for the year 1939 was $1,560. Given the median income for a man at this time was $956, Degani was doing pretty well.

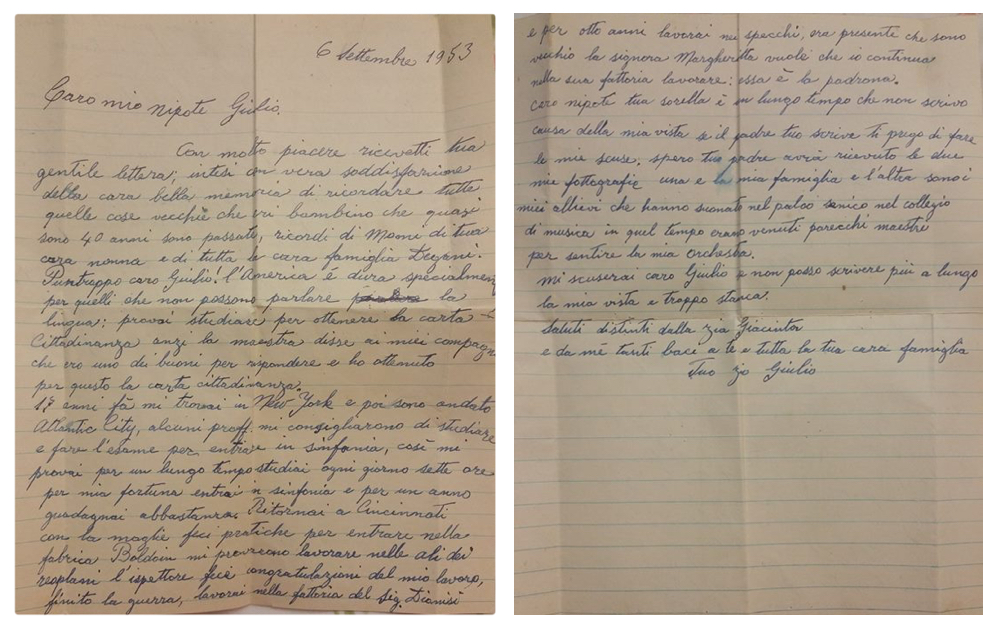

The letter Degani wrote to his nephew in 1953, the year after his retirement, refers to his failing eyesight

By 1946 Degani had moved to 3048 Hackberry Street [9] and started to work for the newly formed ACME Glass company. During these years he continued to run his violin shop part time and in 1949 the Cincinnati Post featured him in an article titled ‘Fine Violin Maker Pursues Craft in Local Workshop’, discussing his legacy of Italian making in the heartland of America. [10] Degani finally closed his Hackberry Street workshop in 1952. By 1953 he had written to Giovanni Musa that he was working for a mirror factory. He was also busy teaching violin and continued working for ACME Glass until the retirement of his violin shop in 1952. [11]

According to family members, after his retirement Degani began to show symptoms of Alzheimer’s. His vision also began to fail due to his diabetes and the letter written to his nephew in 1953 concludes: ‘I can’t write anymore, my eyes are very tired.’ [12] By 1958 he had full-blown dementia. Early the following year Degani moved to 4014 Longford Drive, Dillonville, where he lived until his death. He died aged 83 on May 21, 1959 at Bethesda Hospital in Cincinnati. The Cincinnati Post’s headline read: ‘Death ends Tradition of Degani Family’. [13]

Giulio Degani had great skills as a maker, but he suffered ill health and poor eyesight during the later years of his life; we also now know that due to financial difficulties he worked only part-time as a maker after the onset of World War II until his retirement. Overall his story is one of love of family and the need for personal sacrifice rather than the pursuit of individualistic goals during the hardships of depression-era America.

With thanks to the Degani and Peternella families, Eric Blot, Philip J. Kass, Duane Rosengard and Jim Warren.

Gennady Filimonov is a violinist in the Seattle Symphony and founder of Filimonov Fine Violins.

Next week Dmitry Gindin analyses Degani’s fine instruments and his place in the Venetian school.

Notes

[1] Blackburn Stringed Instrument Collection.

[2] Advert by Chas. Begg and Co. Ltd, London 1917.

[3] Ellis Island Archives.

[4] Letter from Giulio Degani to Giulio Vaccari, September 6, 1953.

[5] Wurlitzer Company Records 1860–1984, NMAH.AC.0469, Smithsonian Institution.

[6] Letter from Giulio Degani to Giulio Vaccari, September 6, 1953.

[7] In the 1980s Duane Rosengard was shown a business card from New York City that featured both Giulio Degani and Jago Peternella’s names and read ‘Corner of 6th Avenue’, suggesting it was situated at the 104 West 52nd Street shop.

[8] His declaration of intention for naturalization was filed on September 3, 1937 in Cincinnati

[9] Cincinnati Directory 1948.

[10] The Cincinnati Post, January 8, 1949.

[11] Letter from Giulio Degani to Giulio Vaccari, Op. cit.

[12] Letter from Giulio Degani to Giulio Vaccari, Op. cit.

[13] Cincinnati Post, May 22, 1959.