Jago Peternella (1886–1970) was a man of many talents – a violin maker, sculptor, painter, engineer and inventor – yet he was often hampered by a lack of employment opportunities. Despite the hardship of the times, Peternella met his personal challenges with determination, ingenuity and hard work. When he struggled to make a living as a violin maker he resorted to repairs and restoration as well as working in other fields. As a result he moved around frequently, working in Verona, Venice, Philadelphia, Atlantic City, New York, Hollywood and finally San Diego.

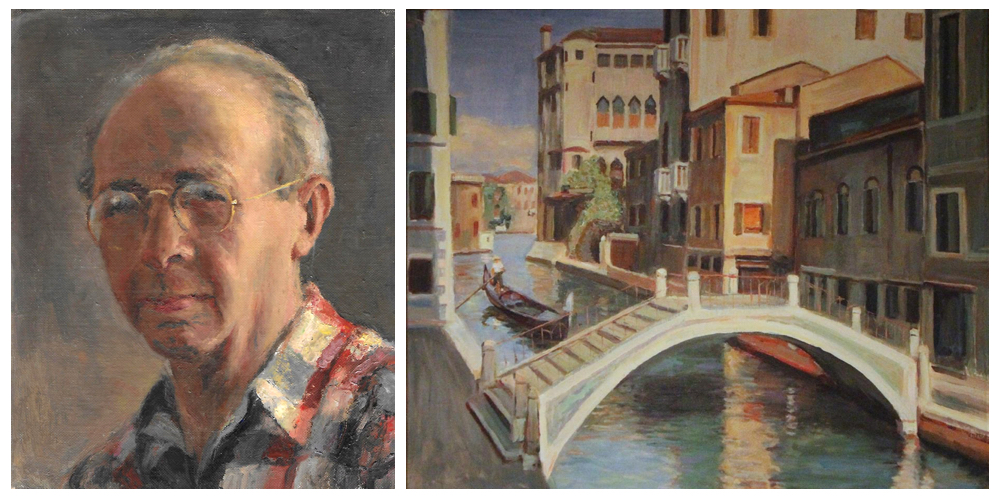

Left: Jago Peternella self portrait, date unknown; right: one of his views of Venice. Images courtesy of the Peternella family

Jago Peternella (at times spelled Petternella) was born on April 29, 1886 in Legnago (near Verona), Italy. He showed artistic gifts at a young age in sculpting, drawing and painting, as well as wood working. He trained as a violinist and became an accomplished player. These interests seem to have merged into an ambition to make violins and, although it is not known where he received his initial training, he appears to have started making instruments in Verona as a teenager. One example exists of an instrument he made dated around 1904, which was donated to UNI School of Music of Northern Iowa upon the death of its owner, Ruth Nordskog Strohbehn, in 2009.

Peternella is thought to have perfected his violin making in Venice with Giulio Degani. [1] While there is no known documentary evidence that he was Degani’s pupil, they were both violinists who played and taught professionally while practising their craft as violin makers in Venice, and presumably would have had mutual friends. Moreover, in 1912 we know that Peternella’s family lived at 3872 Cannaregio, while Degani’s shop was around the corner at Campo San Marziale.

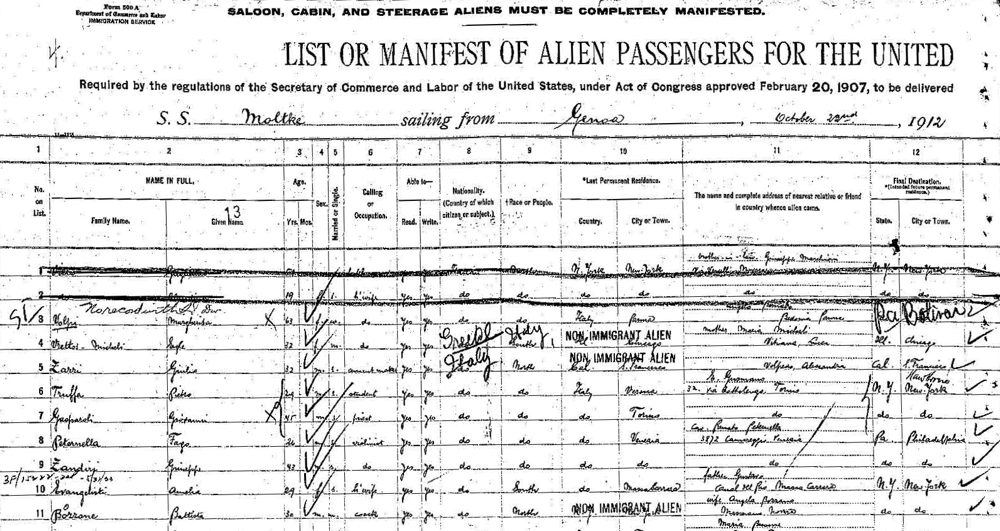

Ship’s manifesto from 1912 showing Peternella’s first entry into the USA (row 8)

According to his US draftcard of 1918, Peternella briefly served in the Italian army, but was honorably discharged due to poor eyesight. Then in October 1912, as political turmoil was building up to the outbreak of World War I in Europe, the 26-year-old Peternella fled Italy with $150 in his pocket. [2] He set sail to America on October 22, arriving at Ellis Island on November 6, 1912. [3] In the ship’s manifesto he described his occupation as ‘violinist’ and the only contact in America he provided was a ‘friend, Henry Mastucci of Philadelphia, PA’, which was his final destination; his last place of residence was listed as Venice, Italy. He entered Ellis Island as ‘Fago Peternella’, a spelling that he confirmed later in his 1930 petition for naturalization in the US.

Peternella appears to have spotted the opportunity provided by America’s steel industry, which over the years of World War I saw its profits dramatically rise, and he started his life in the US working as a draughtsman (a steel mill mechanic) for the Southwark Foundry Machine Company in Philadelphia.

Peternella returned to Italy at the end of 1914. During his time back in Europe he also worked as a violinist with a concert orchestra touring Egypt, finally returning to the US in October 1915 on the SS America. This time the ship’s manifesto reveals that he was traveling with Giulio Degani, confirming the close connection between the two makers. They arrived at Ellis Island on October 19, 1915. Degani was on his way to work for the New York branch of the Wurlitzer Co., while Peternella returned to work at the Southwark Foundry Machine Company.

Peternella (seated front right between two cellists) on tour with an unknown concert orchestra in Egypt, c. 1914

The paths of Peternella and Degani crossed again not long afterwards in Atlantic City, New Jersey, where both of them lived with Frank Coviello, a fellow Italian musician who played at the Apollo Theater in Atlantic City. Degani stayed with Coviello from 1917–1918, [4] while Peternella is recorded as renting a room from Coviello in 1918. Peternella also performed alongside Coviello at the Apollo and worked as a violin teacher. [5] It is evident that Peternella sought out areas of potential economic growth, and Atlantic City at this time was a major vacation destination, as well as a huge attraction for theatrical productions headed for Broadway and beyond, providing many musical opportunities.

In 1919, during the Spanish Influenza pandemic, Peternella decided to visit his family in Italy again. He sailed back for a brief visit and returned to the Port of Boston on October 18. This time, the only contact in America he provided was a ‘friend – Mr Frank Coviello of Atlantic City’ and in 1920 he is again recorded as living in Atlantic City. He was still making instruments and I have seen a Peternella violin labeled: ‘Ha fatto questo violino, nel anno 1920 in Scranton Penn USA…’ (the only evidence that he at some point also worked in Scranton).

It may have been Coviello and his sons Marcel and Francesco (who were both violists) who inspired Peternella to produce a considerable number of violas, which today are highly prized by musicians. Coviello was also instrumental in presenting Peternella to William Moennig Sr of Philadelphia, with whom Peternella established a business relationship. [6]

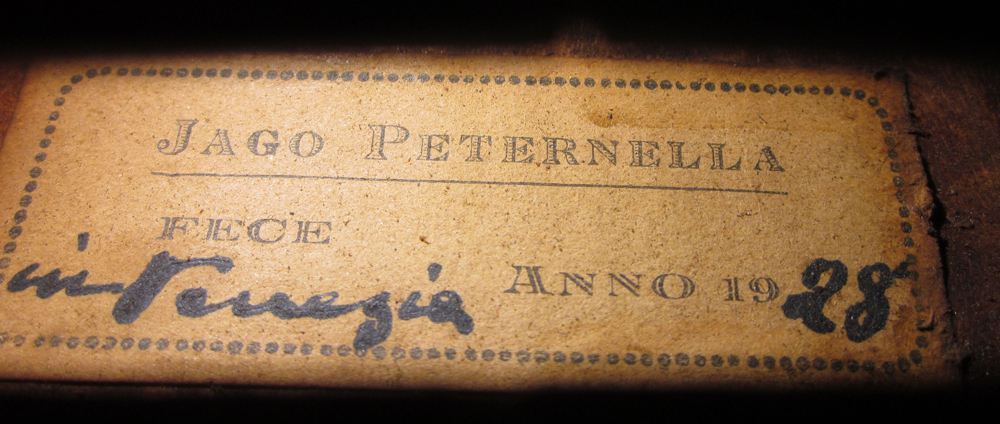

By May 1920 Peternella was back in Venice, where he remained for most of the decade, having set up his shop at Santa Maria del Giglio on the Fondamenta Duodo, not far from the Teatro la Fenice. Perhaps he was encouraged to return by the modernizing influence of Giuseppe Volpi, Count of Misurata (1877–1947), who had helped to bring electricity to Venice. Volpi had built an enormous business empire and had great ambitions to transform Venice into a dynamic, modern city. This period seems to have been a productive one for Peternella and the instruments he made in Venice during the 1920s show a mature and skilled hand. I have seen several examples from 1925, 1927 and 1928 that are very attractive and well made.

However, during this period Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party rose to power in Italy and, according to Dario D’Attili, Peternella was a ‘lifelong communist’. [7] Peternella’s family neither confirm nor deny this suggestion. Nevertheless, it is well documented that anyone who did not embrace Mussolini’s fascist Italy was labeled a communist and it seems likely that at this point Peternella no longer felt safe in his own country.

While in Venice, Peternella had married Rosina (Rosa) Plebani on April 8, 1926. In 1929 Peternella returned with his wife to New York where they settled at 1584 76th Street, Brooklyn. This time, Peternella described himself as a ‘violin maker’ in the ship’s manifesto.

By 1930 Peternella was living at 2511 Pacific Avenue, Atlantic City, a block away from the famous Boardwalk, and had opened his shop a few blocks down at 522 Freeman Bldg (1516 Atlantic Avenue). In the same year he applied for US citizenship in 1930 and received it on December 28, 1932.

A label from a 1928 Peternella violin. Photo: Tarisio

I have come across a viola from this period labeled as made in 1932 in Verona, Italy. Yet by 1932 Peternella had moved once again to New York and was living at 219 East 23rd Street. The same is true of other Peternella instruments that are labeled as Italian yet were clearly made when he lived in the US. Those years were undoubtedly difficult due to the Great Depression and it was probably hardship that led both Peternella and indeed Degani to label some of their instruments as made in Italy rather than the US. It is certain that both understood the value placed on a modern Italian violin versus an American-made instrument.

In New York the Peternellas shared an apartment with Helen and William Johnson, who were to become lifelong friends. Johnson was a violinist who worked in theatre orchestras. Upon moving to his new uptown location at 104 West 52nd Street in 1935, Peternella settled his debts with the Johnsons by offering them two violins he had made that year, one of which Johnson’s grandson Brennan Sweet, Associate Concertmaster of the New Jersey Symphony, still plays (labeled ‘Jago Petternella di Venezia fece 1935’ and signed ‘Jago Peternella’).

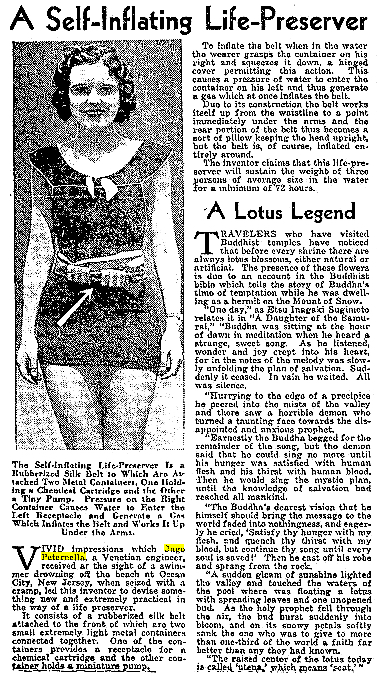

Peternella’s patented life preserver

Peternella was also an engineer–inventor and in 1931 he patented a new style Life Preserver. The Salt Lake Tribune ran a story on June 18, 1933 entitled ‘Self Inflating Life Preserver’: ‘Jago Peternella (a Venetian Engineer) received the idea at the sight of a swimmer drowning off the beach at Ocean City, New Jersey, when seized with a cramp, which led this inventor to devise something new and extremely practical in the way of a life preserver.’ According to his own letters, he was hoping this innovation would change the world and it is indeed an impressive piece of modern gear, described in the article as ‘a rubberized silk belt to which are attached two metal containers, one holding a chemical cartridge and the other a tiny pump. Pressure on the right container causes water to enter the left receptacle and generate a gas which inflates the belt and works it up under the arms.’

Throughout his many relocations Peternella continued his prolific production of instruments. He also maintained a significant connection with Degani and the two makers appear to have established a brief partnership in New York around 1936, as suggested by a business card bearing both their names, probably based at Peternella’s 104 West 52nd Street location. [8] Yet Peternella labels never mention his association with Degani, even though this could have benefited him.

This block of West 52nd Street, from the 1930s to the late 1940s, became home to jazz clubs such as Onyx, Birdland and Three Deuces; known as ‘Swing Street’ or the ‘street that never slept’, it became the center of the jazz world for more than a decade. It was to Peternella’s West 52nd Street location that the very young Dario D’Attili was sent by Simone F. Sacconi to apprentice with Peternella between 1937–39. It is also where Peternella’s young nephew, Joe Orlando, would visit him for violin lessons. Orlando was friends with David Frisina, concertmaster of the LA Philharmonic 1943–73, who himself had a Peternella violin.

Milt Hinton, the legendary jazz bass player, frequented Peternella’s shop at this location and in 1937 he purchased a ‘Matteo Goffriller circa 1740’ from Peternella. According to Hinton, he was looking to get a better instrument and one day Peternella sat him down and said: ‘Notes on a bass spread the sound of the orchestra, make it sound bigger, give it depth. In your band, the bass is not like other instruments, which play many notes. You play only a few and they must be perfect – round and clear and beautiful. So the best bass player is the man with the best bass. And I have found the right one for you.’ [9] This bass was in Milan and had to be shipped over in pieces in a box; upon its arrival Peternella reconstructed it to its full glory. According to the American cellist and bassist Buell Neidlinger, Peternella also made bass bows.

After the death of his wife in October 1941, Peternella moved to the Dauphin Hotel at 67th Street and Broadway and went to work for a fellow Italian, Roger Nestor Chittolini at 153 West 57th Street, for two or three years.

Around 1943–44 Peternella decided to set up his own shop again, this time down the block from Carnegie Hall, at 130 West 57th Street. This was also Emil Herrmann’s third and final business location. The studio building was built in 1907–08 to provide living and working facilities for artists and the New York City Directory confirms that Peternella was still at this location in 1945.

In the same year Peternella met and married Margaret Agnes Carroll, who was 18 years his junior. By 1946 they had moved to Hollywood, California, and in 1947 they visited Venice for several months. The couple took another trip to Italy in 1949 but unfortunately the marriage was not to last and upon their return Margaret declared herself ‘single’ on the ship’s manifesto.

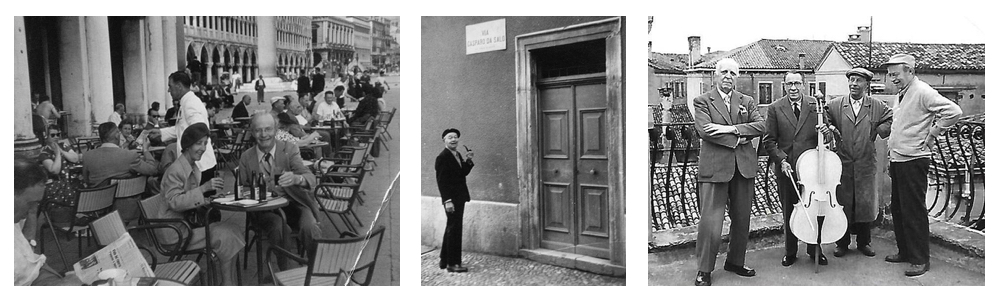

From left: Peternella with Pauline in Venice (1953); Peternella’s trip to Brescia (1953); Peternella (far right) with (from left) Professor Ettore Cassellari, Adolfo Minello and violin maker Luigi Vistoli in Venice in the 1950s

In the 1940s Peternella developed a close relationship with Albert Haines Wallace, a Los Angeles collector who owned four Stradivari violins as well as a Carlo Bergonzi and a Nicolò Amati. He entrusted Peternella with maintenance and repair of his collection and also commissioned him to make several instruments. This is the most likely reason for Peternella’s move to Hollywood in 1946. After Wallace’s death in 1949 his widow, Pauline, a wealthy socialite from Tennessee, became a close friend to Peternella.

Around 1951–52 Peternella contributed to the writing of a book on the Brescian maker Gaspar Bertolotti ‘da Salò’, while still in Hollywood. During the summer of 1953 he and Pauline traveled to Italy, where they visited both Venice and Brescia, including the home of Gasparo ‘da Salò’.

After another trip to Venice in 1955–56 (on this occasion he sailed to Italy with 3 trunks, 4 suitcases, 1 record player and 1 wooden box!) Peternella moved to San Diego. There are many instruments labeled as made in San Diego around this time and it appears to have been a positive period in his life. Peternella finally married Pauline in 1958 and they settled at 3415 Albatross Street in San Diego. At this point his life finally became stable as, thanks to his new wife, he no longer had to worry about finances.

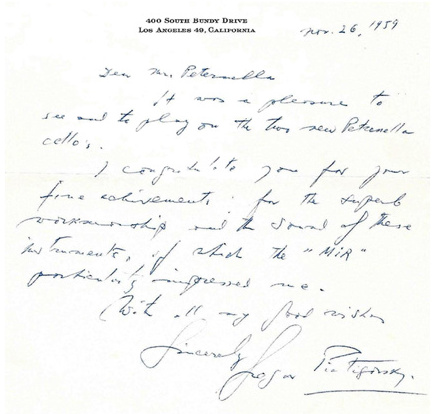

Gregor Piatigorsky’s letter to Peternella, November 1959

Peternella had business relationships with firms such as Lewis & Sons, Kenneth Warren & Sons, Emil Hermann, William Moennig & Son, Metropolitan Music Co., and Rembert Wurlitzer. His musician clients included Bernardo Parrouchi, Alan de Veritch, Signora E. Frank and David Frisina (a former concertmaster of the Los Angelese Philharmonic) as well as Gregor Piatigorsky.

A letter from Piatigorsky dated November 26, 1959 praises Peternella’s instruments:

‘Dear Mr. Peternella,

It was a pleasure to see and to play on the two new cellos. I congratulate you for your fine achievement, for the superb workmanship and the sound of these instruments of which the “Mir” [ “world” in Russian] particularly impressed me.

With all my good wishes

Sincerely Gregor Piatigorsky’

By 1964 Peternella had officially retired from his San Diego business; nevertheless he carried on constructing instruments till the end of his life. According to Jim Warren, between February 1963 and November 1967 the firm Kenneth Warren & Son purchased eight violas and two cellos from Peternella. There were still instruments that were unfinished on his bench at the time of his death.

Peternella’s work during the last few years of his life became heavy handed as his health declined. According to family members, he had always smoked a tobacco pipe and did not believe in visiting the doctor. He was still an avid artist and would spend his free time painting and sculpting. Peternella died in San Diego on June 7, 1970 aged 84. His body was brought back to Verona for burial.

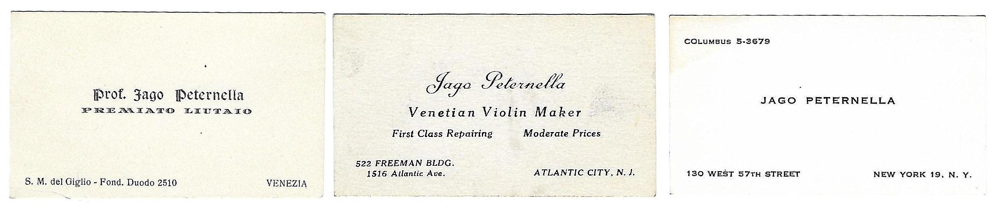

A selection of Peternella’s business cards dating (from left) from the mid-1920s, the 1930s and 1943

Like Giovanni Schwarz (Eugenio Degani’s nephew) and Ettore Siega, Peternella’s work was inspired by Degani and he used personal interpretations of Degani’s models. He considered himself a Venetian maker and described himself as a ‘Violin Maker of the Venetian School’ on some of his business cards. His instruments are described as sweet and robust in tone. Today he is remembered as one of the disciples of the Venetian school.

With thanks to Eric Benning, the Peternella family, Brennan Sweet, Philip J. Kass, Duane Rosengard and Jim Warren.

Gennady Filimonov is a violinist in the Seattle Symphony and founder of Filimonov Fine Violins.

[1] Some experts, including Artemio Versari, believe that Peternella learned violin making with Eugenio Degani, father of Giulio. The Venetian researcher Stefano Pio confirms that there is no written account of Peternella’s formative years, but states that according to the Venetian maker Carlo de March (1904–1993, a pupil of Peternella’s friend Luigi Vistoli), Peternella learned along with Giulio Degani from Eugenio Degani. He would, however, have been very young to do so, as Eugenio Degani died in 1901 when Peternella would have been only 15.

[2] Ship’s manifesto from the SS Moltke, Ellis Island Records.

[3] Ellis Island Records.

[4] Atlantic City Directory 1917–1918.

[5] US Census 1920; Atlantic City Directory 1918–19.

[6] Information from Philip J. Kass.

[7] Information from Philip J. Kass and Duane Rosengard.

[8] This business card was shown to Duane Rosengard by Trieste Rao, the daughter of Giuseppe Musa, in whose house Degani had lived in Atlantic City during the 1930s.

[9] Milt Hinton, Playing the Changes, Vanderbilt University Press, March 2008.