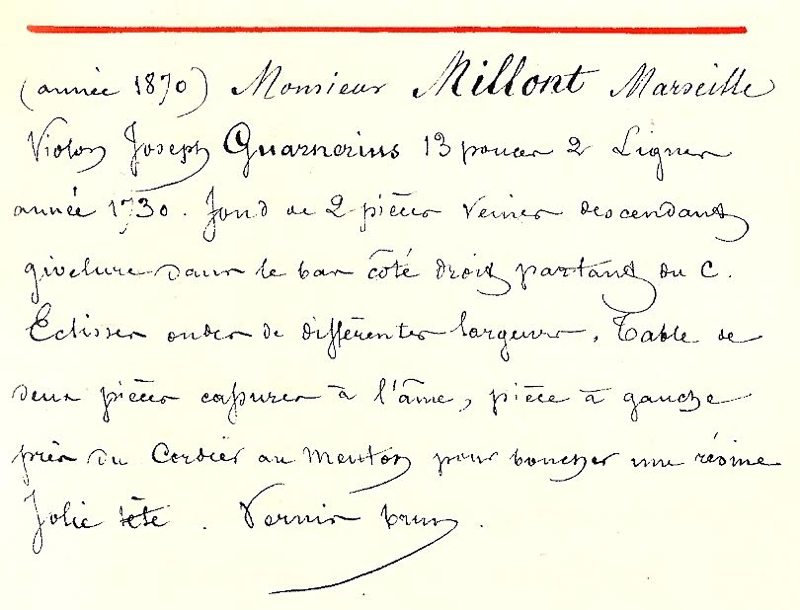

Eugène Gand’s notes from 1870, referring to Monsieur Millont

As with many Guarneri violins, the early history of the c. 1725 ‘Enescu, Cathedral’ Giuseppe Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ remains unknown. It first appears in the notes of Eugène Gand in 1870 when it was purchased from the firm of Gand & Bernardel Frères by Monsieur Millont, a professor at the Conservatory of Marseille. In 1896 the violin was in the possession of a Monsieur Brouzet (possibly Gracchus Brouzet the doctor from Nîmes) who brought it to H.C. Silvestre in Paris in 1896 for expertise. Silvestre certified the violin as being the work of Giuseppe Guarneri ‘filius Andreae’. The ledger of Albert Caressa, who succeeded to the firm of Gand & Bernardel in Paris, notes cryptically in around 1910 that the violin bore a label of Carlo Bergonzi. In 1900 it passed to George Enescu who, according to Caressa, traded in a Stradivari to acquire it. Shortly after Enescu’s death in 1955 the violin was bequeathed to its current owner, the George Enescu National Museum in Romania.

Now acknowledged to be one of the great early ‘del Gesù’ violins from the period of 1722–25, this instrument was owned for over 50 years by one of the 20th century’s most influential musicians, George Enescu, but was left unplayed and almost forgotten in the years after his death until its return to the concert stage in 2008.

The back is in two pieces of handsome quarter-cut maple with an oblique wood-flaw at the lower bass flank. The two locating pins to the back are set on the center-line, bisecting the joint, with the lower pin set several millimeters inside the purfling and the upper pin bisected by the purfle. The arching of the back-plate is remarkably flat at the center and abruptly transitions into the bouts as if the central plateau were left straight off the stroke of a jack plane. This is easily visible with a shadow line to illustrate the contours.

The wood stock used for the ribs of this instrument is mixed: the upper ribs are similar to the back but the center and lower ribs are of different stock with a narrower flame. The upper ribs were originally in two pieces and the lower rib appears to have been a single piece which has since been cut. Interestingly the lower treble rib mitre has been adjusted, most likely originally by the maker, at an extreme angle to connect the differing outlines of the top and back.

Already by the 1720s the gesture of the work was more important than disciplined accuracy. From left: the wood flaw; the oblique angle of the treble rib mitre; the imprecision of the purfling. Photos: Tarisio

One of the fascinating aspects of early ‘del Gesù’ instruments is that they are imbued with unique character despite his youth and the fact that he was working in collaboration with his father. Already in the 1720s the gesture of the work is more important than disciplined accuracy. The purfling of this instrument is at times very imprecise in a way that foreshadows his more mature work of the 1740s.

It is easy to understand how this violin was previously misattributed to Giuseppe ‘filius Andreae’, the father of ‘del Gesù’. During the period 1720–25 father and son were working side by side and distinguishing their work is not always easy. The outline of early ‘del Gesù’ work, with its rounded upper bouts and slightly square shoulders, is derived from the late-period ‘filius’ model. The narrow, high-waisted C-bouts and the protruding upper corners of this instrument could easily pass as the work of ‘filius Andreae’.

The f-holes of the ‘Enescu, Cathedral’ (left) and the ‘Möller, Samsung’ from the same period. Photos: Tarisio

But the clue to distinguishing the two makers often lies in the sound-holes. On this instrument the upper and lower sound-hole wings are very broad and hatchet shaped. The upper wings are a full 8 mm in width and the lower are 9 mm (by comparison typical Stradivari sound-hole wings are approximately 6 and 7 mm). Interestingly, Guarneri’s upper wings are often the same width as his lower wings during this period and occasionally, as in the case of the ‘Möller, Samsung’, they are actually wider. The lower holes themselves are quite small in diameter and not much larger than the upper. Unlike the arching of the back, the top is very rounded in the center section, which serves to further exaggerate the wide setting of the ‘f’s with a dramatic 43 mm between the upper holes.

The head of this violin is of the ‘filius’ type with a concise volute, a very narrow and deep last turn, a narrow chamfer and strong tool-marks from a narrow gauge fanned out like rays on the second turn. The fluting on the back and top of the head is very shallow but becomes deeper and rounded under the chin.

Areas of original varnish give a richness of color to the C-bouts of the back. As with all periods of ‘del Gesù’s work, the violin has toolmarks and character in abundance.

Playing Enescu’s violin: Gabriel Croitoru

Gabriel Croitoru has performed on the ‘Enescu, Cathedral’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ violin since 2008

Gabriel Croitoru (left) with Jason Price and the Guarneri

I won the right to play this marvellous violin through a competition run by the Romanian Ministry of Culture. It was previously owned by George Enescu, who played it for most of his career. When I met Yehudi Menuhin, Enescu’s pupil, he told me that this was the only violin Enescu bought with his own money. His wife was a Romanian princess, Maruca Rosetti-Tescanu, who was very rich and she bought him many instruments. When he died in 1955 he gave his violins to Menuhin, who kept them for one year and then gave them to the princess. She then returned to Romania with the violins and in 1956 she gave them to the Romanian State.

George Enescu, who played the Guarneri for most of his career

The violin had not been played since then. It was kept in very good condition by the George Enescu National Museum and hardly anyone even knew about it. When I touched it for the first time it didn’t seem to need any repairs. I just changed the bridge and of course the strings, but the rest of the violin was intact with no cracks or problems.

I’m very content to play this Guarneri – I prefer it to the Strads I have played because the sound is more round and profound in the bass. When you play such a good violin you have the opportunity to do anything you like – the violin responds immediately. The violin has got used to my style of playing and I have started to understand its secrets. Maybe I will never know all of its secrets, but I would say that my playing has definitely improved since I got it.

Interview by Naomi Sadler