Little is known of the independent work of Francesco Bertolotti, the son of Gaspar (see part 1) and one of the makers active during the second Brescian school. Although he took over the workshop after his father’s death in 1609, there is only one label of his recorded, in the back of a tenor viola that has been considerably modified. He was completely overshadowed by his father’s apprentice Giovanni Paolo Maggini, who joined them in about 1595, when Francesco was already aged 30.

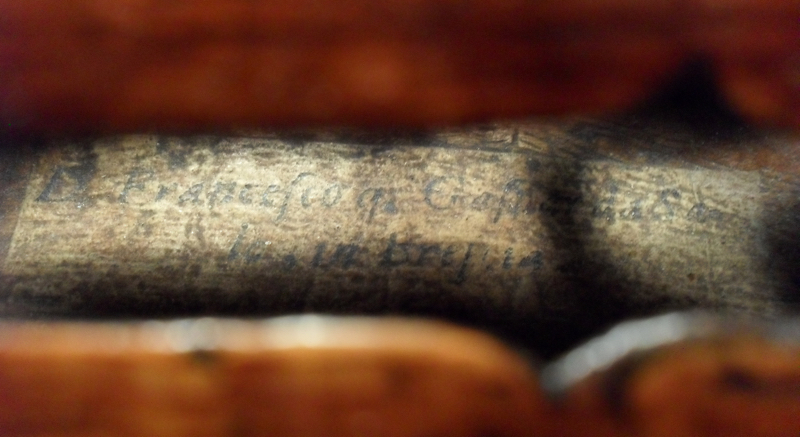

The almost illegible label of Francesco Bertolotti ‘da Salò’ in a tenor viola. Photo: Chi-Mei Museum

Maggini was born in 1580 in Botticino Sera, in the outskirts of Brescia, and gained all his early experience with his master, Gaspar ‘da Salò’. He left the workshop in 1609 to establish his own business in Contrada del Palazzo Vecchio del Podesta, moving to the Bombaserie in San Agata in about 1622, directly in competition with Francesco. His wedding in 1615 was witnessed by Giacomo Lafranchini, his fellow apprentice with Gaspar, who seems to have joined Maggini in his new shop. In 1626 he informed the notary that he had an employee to whom he paid a salary of 300 lire (about $1,500 today), who was presumably Lanfranchini.

Maggini’s output consists almost entirely of instruments of the violin family, which evidently by this date had established their popularity in Italy. Violas both of tenor and contralto size, violins also in two sizes, cellos and basses are known, and Maggini seems to have been fairly prolific. It is often hard to distinguish between his work and that of Gaspar, complicated by the lack of label dates, but this suggests that Maggini’s may have been the dominant hand in the making of violin family instruments in the Gaspar workshop. His technique is altogether more consistent than Gaspar’s, although pure, unrestored instruments from which to observe his methods are very rare.

Stylistically Maggini continued to use doubled purfling on occasion, and more rarely the extra decorative motifs in the back that Gaspar employed. His ‘f’s, often quite slanted across the table, tend to be comparatively slender. Nineteenth-century Maggini copies, particularly by Vuillaume and more commercial German makers, often feature a double spiral scroll, but in fact these are rare in Maggini’s work. His scrolls far more often have the loose spiral of Gaspar, roughly cut and often stopping very short in the eye, with a similar narrow pegbox. There are no instances of the figured pine fronts used by Gaspar, and all his tables show straight, regular grain. The backs can sometimes be of very plain material, but more often feature deeply figured maple, from which his gouge has dislodged small chips in places. The corners are short and quite blunt, following the rib corners, which are also blunt, presenting a very broad chamfered joint.

The ‘Chimay, Sandeman’ Maggini cello, c. 1630–31

More photos

The variation in sizes seen in Maggini’s instruments reflects the output of the contemporary Cremonese makers, who produced small and large violin models as well as small and large violas. The contralto viola is unusual, and Maggini made a small number that are of useful size for modern use, with the ‘F’s set high on the table, giving a further reduced string length. The unique ‘Kievman’ Gaspar contralto viola is actually considerably smaller than the Maggini models. A beautiful cello of Maggini’s, the ‘Chimay, Sandeman’ of c. 1630–31 has a very similar form to the ‘Kievman’, with the same distinctive central f-hole setting. The Hills, in Huggins’ book on Maggini, drew special attention to this instrument as being the direct precursor of Stradivari’s great ‘B form’ cello of the 1700s (Margaret Huggins, Gio Paolo Maggini His Life and Work, W.E. Hill, London, 1976). In outline, the dimensions match to an uncanny degree.

As with the contralto viola and this cello form, Maggini’s basses also anticipated modern trends, and his magnificent flat-backed instruments were widely copied in the 19th century, particularly by influential English makers like Fendt and Kennedy. Maggini also made very large cellos, more typical of the 17th century in general, and his violins also tend to be overlarge. This could also be said to have been an influence on Stradivari’s design of his ‘long pattern’, which he introduced in 1690 but had abandoned by 1700.

For Brescia the plague was a disaster that took many years to recover from – there was virtually no-one to continue the tradition of violin making

Maggini lost his life in the plague that decimated Brescia from 1629, and is last recorded in 1630. This was the same outbreak that nearly brought violin making to an end in Cremona. But while Nicolò Amati fortunately survived in Cremona, for Brescia the plague was a disaster; as far as can be seen, there was virtually no-one to continue the tradition of violin making. Recent research using dendrochronology, however, has shown that a number of instruments previously ascribed to Maggini were made after his death. There is a slight possibility that Lanfranchini may have been responsible, as may have been one Matteo Bente, who came from the town of Maclodio in the province of Brescia and is recorded in the city archive as a violin and cittern maker between 1637 and 1661. Bente’s known work is in the Maggini style, but of a very crude level of accomplishment. One modern interpretation of these posthumous Magginis is that they may have been made by Giovanni Battista Rogeri.

Rogeri’s career as a violin maker was entirely a result of the plague. When Nicolò Amati rebuilt his business in Cremona in the aftermath, he recruited apprentices from outside the city to help him – an unprecedented move in the tradition of violin making. Rogeri came from Bologna, where he was born in about 1642, to reside with Amati in 1661. After two years he moved to the parish of San Giorgio in Brescia and had established his own workshop there by 1664. In 1688 he moved to the Corte dei Polini, where he died in about 1705. His instruments are fascinating, made perfectly with the techniques of Amati, but with many distinctive features. The ‘f’s are long and elegant, the edgework strong and the purfling bold and neat. The varnish seems identical to that of Amati, a fine golden coat laid over a very reflective ground, and the materials are of excellent quality.

A Maggini-style violin attributed to G.B. Rogeri. Photos: Tarisio

More photos

Rogeri heads are distinctive, very much in the Amati style, but cut with a very shallow flute on the back of the pegbox and front face of the scroll, and quite narrow across the eye. He did, however, often produce instruments of a lesser grade with plain materials and scratched rather than inlaid purfling, and some experts believe that he made violins that are deliberately in the manner of Maggini, imitating the f-holes and scrolls, and even the raised arching. It would seem that Rogeri was happy to work in these varying styles, which is possibly the first instance of one maker copying another outside his normal practice. It is no stretch of the imagination to see Rogeri making some extremely effective copies in the earlier Brescian manner either as a mark of respect, or simply as a commercial endeavour.

What we do get with Rogeri at last are dated labels, printed in the Cremonese manner, which allow us to follow his stylistic development and trace the arrival in the workshop of his eldest son Pietro Giacomo, born in 1665. The Rogeris made wonderful cellos, to a distinctive small pattern with markedly flat arching, and often with the most beautifully flamed maple. Rogeri corners are characteristically long and slightly hooked, and become particularly exaggerated in the work of Pietro Giacomo. A second son, Giovanni Paolo, was born in 1667 and may have assisted their father, but seems to have died quite young without leaving his own label in any known instrument. Pietro Giacomo lived until about 1740, but died without an heir to continue the workshop, which consequently closed.

What we do get with Rogeri at last are dated labels, printed in the Cremonese manner, which allow us to follow his stylistic development

Gaetano Pasta is a fascinating maker who followed in the course of the Rogeris. He was born in Milan in about 1679, a son of Bartolomeo Pasta. Bartolomeo, like Giovanni Battista Rogeri, was a pupil of Nicolò Amati in Cremona in 1660. In 1673 he settled in Milan, where his sons Christoforo, Domenico and Gaetano were born and worked as violin makers (although no instruments by Christoforo are recorded). Gaetano moved to Brescia in about 1694, and his work is so strongly influenced by Rogeri that it is no stretch to assume that they worked together in some way. On his own labels, however, he calls himself ‘Milanese, allievo dell Amati di Cremona’. His style is of the less refined manner of Rogeri, the detail crude and the purfling sometimes scratched rather than inlaid, but the outline and modelling is fine, robust and classical.

Cello by Pietro Paolo De Vitor dated c. 1730. Photos: courtesy Chi-Mei Museum

More photos

Other makers of the second Brescian school include the wonderfully named Domenico Mezzabotte, who was active from about 1720 to 1766 but was not an obviously well-trained maker. The Venetian Pietro Paolo De Vitor is rarely encountered, but his work in Brescia in the period 1735–40 does seem to be refined and skilful with distinctive similarities to Rogeri and Pasta, but with a rather bloated arch.

In general, as elsewhere in Italy, violin making in Brescia had fallen into decline by the late-18th century. Its influence had been fundamental to violin making throughout Europe, and its pedigree stretched back further than Cremona. The designs of Gaspar and Maggini were probably an influence on Stradivari and Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, and are still seen clearly in modern viola and double bass making. Once celebrated as the inventors of the violin, they were at the very least pioneers with a wonderfully sustained legacy.

John Dilworth is a maker, writer and expert. He has written extensively about fine instruments and their makers, and is a co-author of ‘The British Violin’, ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ and ‘The Voller Brothers’ among other books.