The violin making histories of Brescia and Cremona are fascinatingly different. Both similarly sized towns in Lombardy, they share a mutual rivalry even down to the present day, which dates back to the part that Cremonese mercenaries played in the brutal ‘Sack of Brescia’ by the French army in 1512. Their political history is certainly different. Brescia was the first northern city to align itself with the Republic of Rome in the first century BC and in later centuries it became a part of the Veneto, and a rich and brilliant city loyal to ‘La Serenissima’. It was to Brescia that Isabella d’Este, the great Renaissance patroness of music, came to find viol and lute makers at the end of the 15th century.

The town’s early luthiers are sadly little more than names to us now. Giovanni Maria Lanfranco’s Scintille di Musica, published in Brescia in 1533, is a remarkable early text on music and instrumentation. The names of Jacobo Dalla Corna and Micheli Zanetto are recorded there as instrument makers, and Dalla Corna appears elsewhere in Brescian records as ‘magistro a leutis’ and later is credited with ‘lirii’ and ‘violini’ from 1524, while Zanetto is listed as ‘Ioannettus de li violettis’ in 1527.

The f-holes of this Peregrino Zanetto viola from c. 1560 have typically pointed wings and large eyes. Photos: Tarisio

More photosZanetto is important because a few instruments attributed to him or his son Pellegrino still survive. These are ambiguous, however; they have been cut and remodeled, and it is hard to distinguish their original form although they were all larger than violins and have been subsequently reduced to function as violas. What is more, Zanetto (Micheli or Peregrino), like all the early Brescians, never dated his labels, so placing them historically is a vague speculation at best. The surviving Zanetto instruments are ascribed to dates around 1580, but have remarkably well-conceived archings, not as high or bulbous as many subsequent Brescian instruments. The corners are long and elegant, and the f-holes, like early violin family instruments of almost every origin, have very pointed wings and large eyes. What does seem to set the tone of Brescian school work in general is the free carving of the head, which is not so well defined as Andrea Amati’s work; the pegbox has a distinctive viol-like form, with a fairly flat chin and short throat, and the volute sharply thrown back.

Giovanni Maria da Brescia, treble viol, 2nd half of the 16th century (WA1939.27). Image © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Other makers we know from archival references include Battista Doneda, Francesco Inverardi, Palanzino Palancini, Gugliemo Frigiadi and Giovita Rodiani, all recorded as ‘magister a violinis’, a term used in Brescia from at least 1530, which used to refer to all bowed instruments. There is also Giovanni Maria ‘da Brescia’ whose work from Venice we do know, thanks to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, which contains a beautiful treble viol and a charming small viola da braccia. [1] This list of instrument makers from the 16th century is fascinating and important, and seems to have no equivalent, at least so far discovered, in Cremona.

The Virchi family, master woodworkers and makers of citterns and organs, whose traces can still be found in the many ancient churches of Brescia, are also highly significant. They were possibly the first teachers of Gaspar ‘da Salò’, the most famous Brescian violin maker, since they also had a home in Trobbiolo, a parish of Salò.

Gaspar was thought for generations to have been the first violin maker of all. Even the Hills seem to have been under that impression

Gaspar was thought for generations to have been the first violin maker of all. Even the Hills seem to have been under that impression in 1931, when they discussed the origins of violin making in Cremona in their book on the Guarneri family. [2] They admit to drawing a blank in their researches into Andrea Amati and speculate that he may have received his training in Brescia. It is a reminder of how much progress has been made in research into the lives of the violin makers since then, but even so Andrea Amati remains a very little-understood figure.

By contrast there is a surprising amount of biographical information about Gaspar available to us, a great deal of it through his tax returns, recovered from the city archives. Born Gaspar Bertolotti in Salò on Lake Garda in 1540, he came from a family of musicians, his father Francesco recorded variously as a painter, ‘sonadore’ (musician) and ‘violino’. By 1563 he was living in Brescia in the Contrada delle Cossere in the parish of San Giovanni, and in 1566 was first recorded as a violin maker. At the birth of his son Francesco in 1565, the godfather is given as Girolamo Virchi.

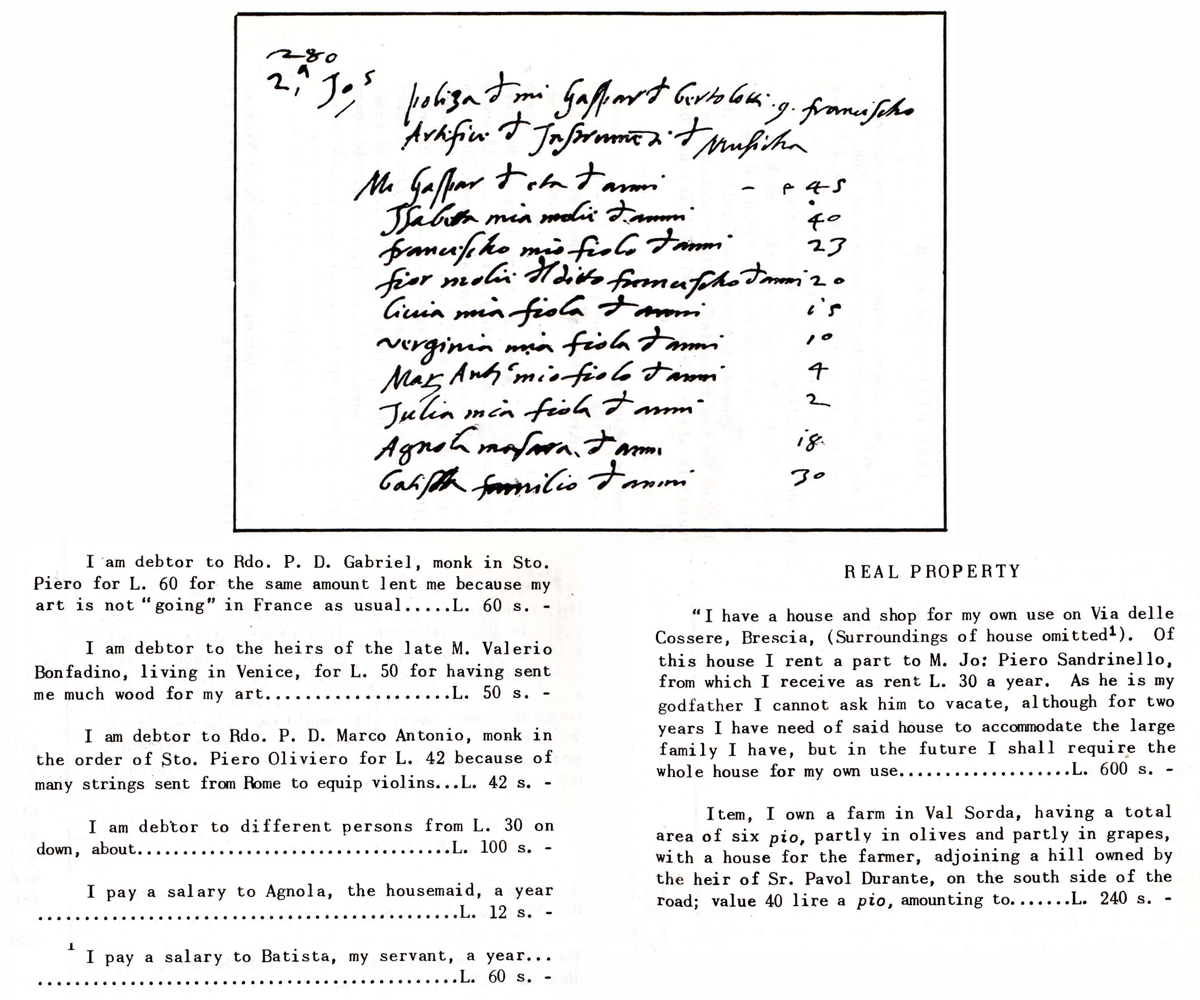

Gaspar’s tax statement for 1588, showing the members of his household (top) and some of his sources for materials (from Robert E. Andrews, ‘Gasparo Bertolotti, Da Salò’)

A tax deposition of 1568 relates Gaspar’s business as ‘maestro di violini’, living in a rented house, with instruments in store to the value of 50 ducati, equivalent to about $1,250 today. By 1581 he was able to buy a house and land outside the city in addition to the workshop. Another tax statement in 1588 shows his circumstances to have improved substantially, with stock worth 500 lire, roughly 100 ducats (or $2,500 today), and copious amounts of beans, wine and olive oil from his farm. An estimated value of one of his instruments held in stock works out to four years’ salary paid to his housemaid. The same statement also reveals that he was accustomed to exporting instruments to France, and that he bought his wood in Venice and his strings in Rome.

The French connection suffered in 1588; the tax statement actually says that Gaspar has had to borrow money to cover for the failure of his exports to France in that year. This is understandable since France was then in the grip of the civil war of the ‘Three Henrys’, Protestant and Catholic rivals to the throne. But the connection to France extended to an assistant working for him in 1578, one Alexandro di Marsilis (Marseilles). At about this time Gaspar’s son Francesco would also have been introduced to the workshop, being by then 13 years old. They were subsequently joined by one Giacomo Lafranchini and the better-known Giovanni Paolo Maggini. In 1599 Gaspar acquired another house in Brescia, possibly as a retirement home. His workshop was obviously a productive and thriving business, and Gaspar an acute and able merchant as well as a craftsman. When he died in 1609, his son became the heir to the workshop, which he continued until his own death sometime around 1620.

His workshop was obviously a productive and thriving business, and Gaspar an acute and able merchant as well as a craftsman

Gaspar’s legacy is a large one, both in variety and historical importance. Although his violins are rare, he made many different forms of stringed instruments, from citterns to violones and double basses, and from violas da braccia to violas ‘proper’. All this was apparently lacking from the Cremona workshops of his contemporaries, the Amati Brothers. Any Amati instrument other than a violin, viola or cello is extremely rare, and it seems to us that their entire work was concentrated on the violin family, as if it was their own personal ‘patent’.

Yet in Brescia, as in Venice in the 16th century, the cittern and viola da braccia were very popular. All sorts of hybrid instruments appear too – whether Gaspar was experimenting himself or merely responding to the demands of local musicians we cannot know. The Ashmolean Museum alone is home to a fine cittern with a carved female head and Adam and Eve depicted on the back, a two-cornered viola da braccia converted into a viola (the Brussels Musical Instrument Museum has a similar, though larger instrument) and a bizarre-looking viola da gamba of curious construction. The range in style and craftsmanship is striking too. This might be because there were several craftsmen at work in the shop, but also, as with the Amati, it’s likely that there were more prestigious commissions among the daily output to which special care was given.

The c. 1562 ‘Ole Bull’ by Gaspar ‘da Salò’ violin perhaps marks his transition to making violin-family instruments

Gaspar’s masterpiece, if one instrument has to be singled out, is the beautiful violin currently held in the Industrial Museum in Bergen, once in the possession of Ole Bull. The level of carving and intricate inlay on this instrument is breathtaking, with a carved and painted cherub’s head surmounting the pegbox (mistakenly attributed to the Florentine sculptor and goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini in many sources), familiar interleaved purfling motifs in the back, and doubled courses of purfling each made up of five individual strands.

The carved heads provide a strong link with Girolamo Virchi, the woodcarver who was godfather to Gaspar’s son Francesco. A beautiful cittern in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna with a brand mark on the back of the peghead ‘Hieronymus Brixiensis’ (Girolamo of Brescia) has very similar polychrome carved ornamentation on the pegbox, in this case a graphic depiction of the Roman heroine Lucretia stabbing herself in the breast. The brand is remarkably similar in form to that of the Ashmolean’s Gaspar cittern. Organ lofts in Brescian churches attributed to the Virchi brothers have similar painted carvings of cherubs and other characters.

The great contradiction in Gaspar’s work is the evidently hurried work of much of it, and the intricacy and detail in others

Whether Gaspar himself trained as a woodcarver or this work was tendered out to specialist tradesmen is difficult to say. The great contradiction in Gaspar’s work is the evidently hurried work of much of it, and the intricacy and detail in others. The scrolls of his violins and violas are astonishingly crude by comparison – no two quite the same, and apparently improvised to the loosest plan, the pegboxes particularly slender from the back and front aspects. The purfling, while often doubled and enhanced with trefoil forms, is on close examination very crudely fitted.

Gaspar’s technique is hard to interpret. He probably did not use a form in the same manner as the Cremonese; his violin models are varied in size and outline, but typically rather elongated compared with the Amati. They probably lacked internal linings, as there are some surviving instruments still in this state, while others seem to have linings added later. The bass viol in the Ashmolean has no trace even of a bass bar, merely a thicker area left running down the centre part of the front. The violins and violas were also probably made with a ‘through neck’, that is without a separate top block, the neck simply extended through the upper bouts and secured directly to the back. This can be deduced from the fact that the backs have no flat platform for the location of a substantial block, either at the upper or lower end. Interior surfaces are also finished with a coarse ridged tool, either a toothed plane or more likely a curved rasp. The archings are generally quite full, and although some have very pronounced recurves around the edges, some examples have edges with no relief whatsoever. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Gaspar’s work are the long f-holes, with narrow, pointed wings and circular finials of equal size top and bottom, which are also bevelled on the interior edges, as the soundholes of viols often are. Many of these characteristics are shared among other early northern European schools in Germany, Poland, the Netherlands and England, possibly indicating the extent of the export and popularity of Brescian school work in the 17th century.

Gasparo Bertolotti ‘da Salò’ viol, possibly bass, c. 1580 (WA1939.22). Image © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

While Gaspar made predominantly large, ‘tenor’ violas, one contralto, the ‘Kievman’ is an exceptional example. Cellos are rare and it is entirely possible that those surviving were not made as four-stringed instruments. There are few that retain their original head, and those that are known seem to have been made originally for five pegs. An interesting aspect of Gaspar’s work that may also provide a clue is his wood choice. Much is made of the ‘cedar of Lebanon’ that appears in the fronts of many instruments, including the Ashmolean’s bass viol (pictured). Distinctive because of its very strong cross-grain ‘bear-claw’ figure, this material is most probably not cedar but a local variety of pine. What is striking is that it appears in all his viols, basses and citterns, but not in his violins and violas. The instruments clearly made as members of the violin family all have fronts made of conventional straight-grained Alpine spruce. It may be that he was following an already established convention that this spruce was the best material for violins, while the local softwood was reserved for other classes of instrument. The ‘cellos’ attributed to Gaspar have fronts made from the figured pine.

There is, however, a basic problem in defining all these instruments, and even Gaspar’s stylistic development as a whole, in that no Brescian maker ever, to my knowledge, actually dated their labels. Speculative dates attached to various instruments are based on no material evidence, and in most cases rely on imitation labels added in later interventions. We cannot track exactly when Gaspar made his first violin, or whether his citterns and viols predate the violins or were made at the same time. We can barely begin to guess where Francesco’s or Maggini’s hand appears in the work. My own guess would be that the elaborately carved work on various forms of viol and citterns, using the figured pine, is from an early period, while the violins and violas, generally of more restrained appearance and using straight-grained spruce, date from later in his career.

We cannot track exactly when Gaspar made his first violin, or whether his citterns and viols predate the violins or were made at the same time

If this is the case, the Bergen ‘Ole Bull’ violin, which has aspects of both styles and stands slightly apart from his other work, might mark the transition from viols to violins. And here there is some evidence of the actual date of its making. Sara Bull, Ole’s second wife, wrote an account of the violin in 1902 [3] that is thoroughly reported in Robert Andrew’s book on Gaspar. [4] According to this it was made in 1562 for Cardinal Ippolito Aldobrandini of Florence. In 1566 he was appointed Suffragan Bishop of Tyrol, and the violin was presented to the Archduke Ferdinand, who stored it in the Treasury room of Castle Ambras in Innsbruck, where it was later joined by the Girolamo Virchi cittern.

Much of this is disputed, since evidence points to Gaspar still living in Salò in 1562, but the two instruments are described in an inventory of Castle Ambras in 1598, and it is intriguing that the Virchi cittern and the Gaspar violin were kept together. It is also worth noting that the label in the violin is in Gothic type, not the usual Roman type of every other Gaspar ticket.

Violas made by Gaspar (left) and the Brothers Amati. Although there are superficial similarities, it is remarkable how little DNA they share. Photos: Tarisio

Such historical ambiguity contributed no doubt to the idea that Gaspar invented the violin. The underlying reason, though, is presumably that his violins and violas seem to us more primitive in appearance than the highly sophisticated designs of Andrea Amati in Cremona. What is interesting is how little DNA is shared between the two makers. It is plain that they used quite different methods, techniques and materials to make their violins. It makes no sense that Amati could have been a pupil of Gaspar from that view alone. What it may imply is that the familiar template of the general violin outline, with purfled overhanging edges, f-holes and scroll-topped pegbox, was an established form that both men were interpreting in their own differing ways. For early makers and musicians in northern Europe, the Brescian rather than Cremonese models seem to have been the first true violins and violas they encountered and then imitated.

What we do know historically is that Gaspar is unlikely to have made anything of significance before he arrived in Brescia in about 1563, while in Cremona, Andrea Amati was then already about 60 years old. Amati had made three-stringed violins from at least 1542 and the magnificent Charles IX set, which largely defines the classical violin, was begun in 1564. Gaspar’s true contemporaries were in fact Andrea’s sons, Antonio and Girolamo.

In part 2, John Dilworth explores the work of the second generation of Brescian school violin makers, led by Giovanni Paolo Maggini.

John Dilworth is a maker, writer and expert. He has written extensively about fine instruments and their makers, and is a co-author of ‘The British Violin’, ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ and ‘The Voller Brothers’ among other books.

Notes

[1] John Milnes (editor), Musical Instruments in the Ashmolean Museum, OMIP, Oxford, 2011.

[2] W.H., A.F. & A.E. Hill, The Violin Makers of the Guarneri Family, W.E. Hill & Sons, London, 1931.

[3] Sara Bull, Ole Bull’s Gaspar Cellini Violin, Bergen, 1902.

[4] Robert E. Andrews, Gasparo Bertolotti, Da Salò, Berkeley California, 1953.

General references

– Eric Blot, Liutai in Brescia 1520–1724, Eric Blot Edizione, Cremona, 2008.

– Flavio Dasseno and Ugo Ravasio, Gaspar da Salò e la liuteria Bresciana tra rinascimento e Barocco, Editrice Turris, 1990.

– Liuteria e Musica Strumentale a Brescia tra Cinque e Seicento vol.1, Fondazione Civiltà Bresciana, 1992.