The instruments of the 19th-century French school show a great price disparity in today’s market: Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume sits at the very top, far in front of the next cluster of makers. This kind of gap is not seen in other schools of making and I wanted to look at what the market was like in the 19th century in order to understand why there is such a price difference today.

In fact, advertisements and auction records from the first half of the 20th century show that Vuillaume’s instruments were no more sought-after than those of other fine French makers, such as Nicolas Lupot, Gand père or Pierre Silvestre. Moreover, today’s price curve does not reflect the wide range of high-quality craftsmanship available in 19th-century France, as the work of several talented French makers featured in our October sale reveals.

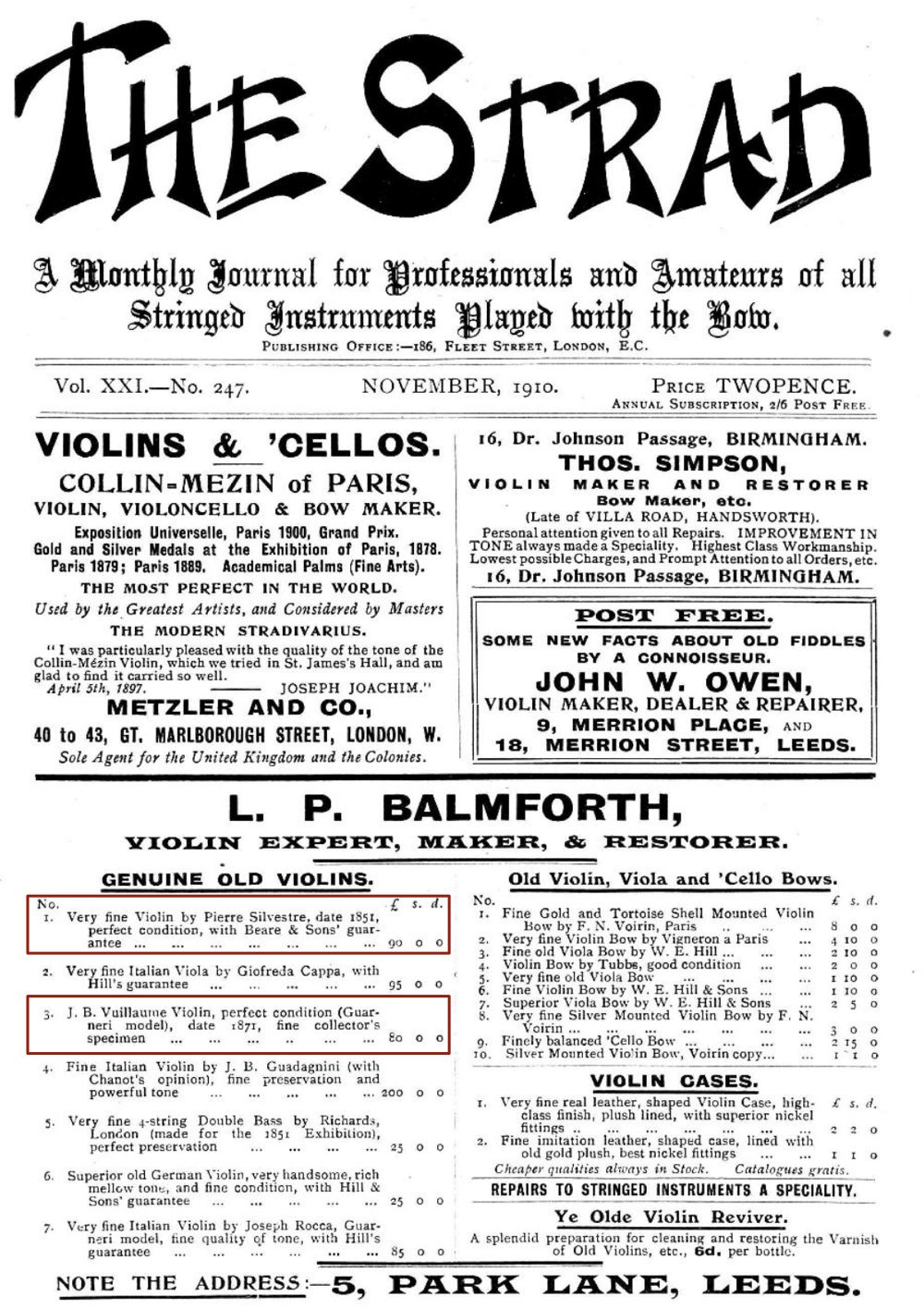

An advert from The Strad in 1910 shows Silvestre valued above Vuillaume

Let’s go back to 1806, the year that Nicolas Lupot, the most prestigious French luthier at the time, relocated his shop to the rue Croix des Petits-Champs. The street was right across from the Louvre where his employer, the King of France, resided. In 1810 Charles François Gand père opened his own shop in the same street, at no. 5. Gand was Lupot’s most important apprentice and also became his son-in-law. He took over Koliker’s five-storey building at no. 24 in 1820, then acquired Lupot’s inventory and official title four years later. It’s easy to imagine the prestige of the Lupot and Gand workshops, and how central the rue Croix des Petits-Champs was to the instrument trade in Paris. In the year of his death, Lupot violins cost around four times more than Vuillaume’s, [1] yet in the past decade they have been priced at about 20% less than Vuillaume.

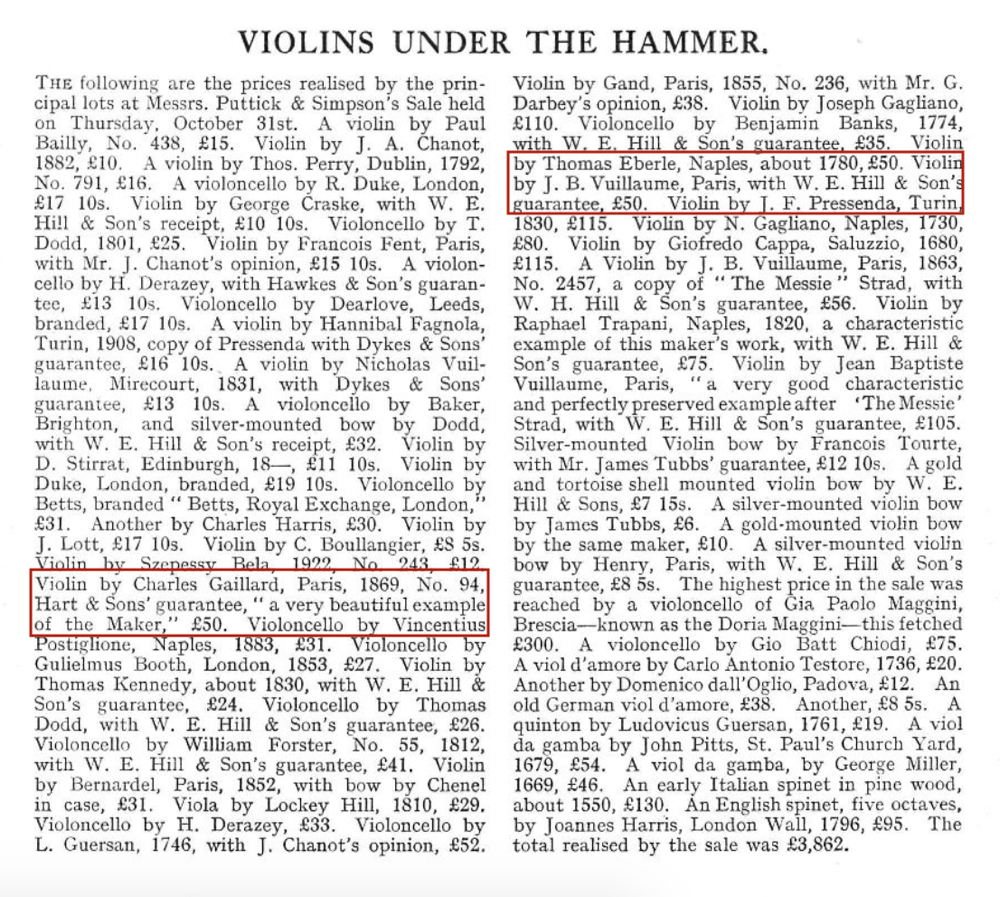

This auction report published by The Strad shows that Puttick & Simpson sold violins by Gaillard and Vuillaume for £50 each in October 1929

Vuillaume himself studied in Mirecourt like everyone else. There he met Georges Chanot I, and they graduated and arrived in Paris together around 1818. Georges’ elder brother, François, had a shop in Paris, and Jean-Baptiste and Georges both worked there, helping him to build the guitar-shaped instruments for which he had obtained a patent. Georges was then hired by Gand père in 1821, before setting up shop in rue de la Vrillière, about 200 meters from rue Croix des Petits-Champs. Vuillaume opened his own workshop in rue Croix des Petits-Champs in 1825, first at no. 30, then three years later at no. 46.

Georges Chanot I

Chanot I and Vuillaume remained close friends all their lives and they became the most celebrated copyists of their time. The fine Stradivari copy by Chanot offered in our sale shows his skill. Built at the height of his career, it is in near mint condition. In order to copy successfully, one must have a thorough understanding of the original, and both makers were also the most knowledgeable experts of their time. Vuillaume even worried: ‘When Chanot and I will both be dead, who will know the old Italian instruments?’ [2] Chanot, however, lacked Vuillaume’s charisma and commercial talent and his career was accordingly less successful.

Nicolas Vuillaume

Nicolas Vuillaume was one of Jean-Baptiste’s four brothers, and was invited by Jean-Baptiste to join him in Paris in 1832, after the death of his wife and son in an outbreak of cholera that ravaged the city of Mirecourt. After ten years in Paris, he moved back to Mirecourt to build ‘companion violins’ under the Sainte Cécile and Stentor brands. The Stentor brand was patented in 1850 and likely derived its name from the Greek herald, whose ‘voice was as powerful as fifty voices of other men’ according to Homer. [3] The instruments were made in the white and sent to Paris for Jean-Baptiste to varnish and finish, before being sold all over Europe. These were almost exclusively made on a Guarneri model, [4] and the violin in our October sale is a good example of this.

Pierre Silvestre

Concurrently, Pierre Silvestre was employed as the head of Lupot’s workshop, and Lupot’s influence is evident in the 1862 Silvestre example in our sale. He kept his position when Gand père took over the workshop before establishing himself in Lyon in 1829 with his brother Hippolyte. His instruments are about ten times rarer than Vuillaume’s, totalling about 350 compared with the 3,001 signed by Vuillaume, [5] and show great character and individuality. His work was popular at the time and in 1910 a violin by Silvestre was offered for 10% more than a Guarneri model by Vuillaume (see The Strad advert above)!

Charles Gaillard

Charles Gaillard was the apprentice of Charles Adolphe Gand (the son of Gand père) and later became head of Gand’s workshop until he opened his own Parisian shop in 1851. His work is naturally very close to Gand’s in quality and aesthetics, as shown by the example offered in our sale. In October 1929 a Charles Gaillard violin was sold by Puttick & Simpson for £50, the same price as for a Vuillaume violin, although the condition and model of the latter is unknown. It is worth noting that in the same sale a ‘perfectly preserved’ copy of the ‘Messiah’ Stradivari by Vuillaume sold for £105, thus a rounded-down ratio of 2:1. Note the ratio of 34:1 between the Vuillaume and Gaillard violins in our sale.

Paul Bailly

Paul Bailly was a pupil of Charles Gaillard’s younger brother, Jules, in Mirecourt. He then worked in Brussels for Nicolas-François Vuillaume before being employed by Jean-Baptiste himself from 1864–68, during his last period of making. He proudly mentions his former employer on all his labels, sometimes even above the medals he won for his work in Sydney, Melbourne and Paris – a tribute to Vuillaume’s success. Bailly’s collaboration with Vuillaume took place after the latter’s purchase of the ‘Messiah’, which changed Vuillaume’s aesthetic vision thanks to its unworn varnish; Bailly himself used both shaded and non-antiqued varnish for his instruments.

Bailly’s labels between the years 1868 and 1885 typically do not mention the city in which the instrument was made, as he traveled to (and presumably worked in) Brussels and Chicago during this time. We do know that by 1891 he was established on Wardour Street in London, right next to W.E. Hill & Sons, Hart & Son and Chanot II, [6] while in 1898 he was employed by Harry Dykes of Leeds. This collaboration seems to have been difficult, however, as he moved back to Paris that same year. The example offered in our sale is undated but numbered 851. Judging by Bailly violins inscribed ‘No 824, 1893’ and ‘1898 no. 1027’ in our previous sales, we can assume the example in our October sale was made around 1894.

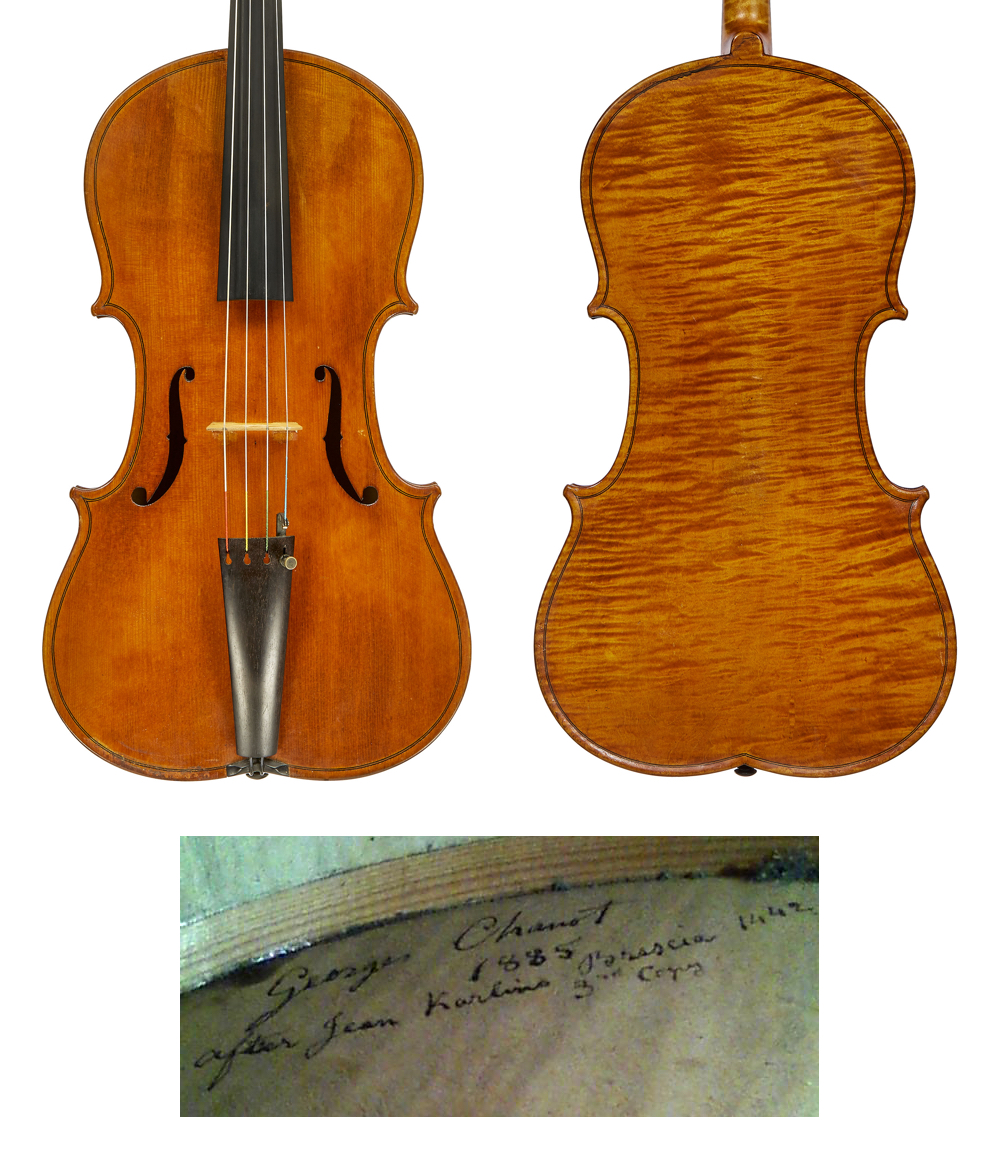

Georges Chanot II

Another – albeit financially more successful – Frenchman in London was Georges Chanot II, son of Georges Chanot I. Georges II was a renowned expert (see the numerous instruments sold ‘with opinion from Mr. Chanot’ in auction catalogs of the time) and a fine copyist like his father. We offer a peculiar Georges II viola in this sale. It is inscribed to the inside back, ‘Georges Chanot, 1885, after Jean Karlino Brescia 1442, 3d copy’ and illustrates an interesting 19th-century error of expertise.

Unusual viola by Georges Chanot II, London, 1885, with an inscription referring to the fictitious Brescian maker Jean Karlino. Photos: Tarisio

More photosIn 1804 François-Joseph Fétis, the musical authority and a close friend of Vuillaume, is said to have seen a violin bearing the label ‘Joann Kerlino, anno 1449’ at Koliker’s shop in Paris. No documentary evidence of a Brescian maker named Kerlino or Karlino has been found. However, Fétis stated in his 1856 biography of Stradivari that ‘an Italian correspondent of Vuillaume who has been dealing in instruments [presumably Luigi Tarisio] confirms there was a luthier named Jean Kerlino in Brescia around 1450,’ following which all sorts of spurious Kerlino labels and inscriptions started appearing on the market. [7] One example was even exhibited in 1873 at the South Kensington Museum, listed in the viola section as: ‘A Joan Karlino, Brescia, said to be of the year 1452, lent by M. G. Chanot.’ [8] This did not fool the connoisseur Charles Reade, however, who writes that the instrument was in fact made by ‘Ventura Linarolli of Venice […] about the year 1520,’ [9] (see example of an original Linarol viola). Koliker was well known for his restoration and modernising of antique instruments, and had probably switched the neck of the instrument seen by Fétis, presumably with the support of none other than Tarisio himself!

Pierre Charles Jacquot

The legacy of the extended Vuillaume family continues with Pierre Charles Jacquot, who was the son of Charles Jacquot and nephew of Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume. He worked in Nancy, which became the most important city in Eastern France after the loss of Alsace and Moselle in the 1870 Franco-Prussian war, and now bordered the newly formed Germany. We previously sold an 1888 Jacquot instrument proudly bearing the city’s crest, and the example offered here is very similar. Jacquot’s fine work won numorous prizes in Europe and the US between the 1860s and 1890s, following which he was awarded the French Légion d’Honneur.

Vuillaume established himself as the most influential violin maker of his time. Given his prolific output and its remarkable consistency in quality, it’s easy to understand why his work has become such a stable investment. An astute businessman, Vuillaume also employed many excellent craftsmen, causing their efforts to fall into oblivion by comparison if we judge by the prices of their instruments today. Most of these fine 19th-century makers simply lacked Vuillaume’s charisma and the financial means to promote themselves. Yet the intrinsic quality of their work is not far from Vuillaume’s, as the selection of 19th-century French school violins in this sale demonstrates. Looking at the evolution in prices for French bow makers contemporary to Eugène Sartory, those who dare to bid off the beaten path may well be rewarded in the future!

Marie Turini-Viard is Tarisio’s London-based specialist.

These 19th-century French school instruments are all available in our London October sale. View the full October sale catalog.

Notes

[1] Sylvette Milliot, S., J.B. Vuillaume et sa Famille, Amis de la Musique, 2006, p. 275.

[2] Ibid, p. 277.

[3] Homer, The Iliad, v. 783.

[4] Rémy Campos (ed), Violons, Vuillaume, Musée de la Musique, Paris, 1998, p. 260.

[5] Towry Piper, ‘Pierre Sylvestre’, The Strad, May 1916.

[6] Advertisement in The Strad, December 1891.

[7] Rémy Campos (ed), Violons, Vuillaume, Op. cit, p. 134.

[8] Carl Engel, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Musical Instruments in the South Kensington Museum, George E. Eyre, London, 1874, p. 363.

[9] Charles Reade, Cremona Violins: Four Letters Descriptive of those Exhibited in 1873 at the South Kensington Museum, Alexander Broude Inc, New York, 1873, p. 9.