In contrast to the scarcity of documents about Bernardo Calcagno’s life (see part 1), the plentiful number of surviving instruments from his workshop provide good evidence about his working methods. However, some questions remain, including whether Calcagno used an internal mould for his instruments. While there is evidence of the internal mould in the work of the Genoese maker Paolo Castello, this doesn’t appear clearly on Calcagno’s interiors.

Overall, Calcagno instruments seem to have been constructed according to the usual principles of Italian violin making: the necks were firmly set with the use of two or three nails in the upper block. The blocks are often made of pine; however, in some cases Calcagno used a different type of wood for his corner blocks, such as lime or a similar local species from the Appenine hills. The linings are usually of beech: these were simply abutted against the corner blocks, not mortised into them, and then quickly trimmed. The whole interior gives the impression of a spontaneous and freewheeling approach to violin making: the surfaces of the ribs show marks from a toothed-plane blade; the split surfaces of the corner blocks have not been finished; and the linings appear cut and scraped without any care for the cosmetic result.

The linings are usually made of beech and quickly worked, as seen on an example dating from the 1740s. Photo: courtesy Alberto Giordano

The linings are usually of beech: these were simply set against the blocks without any mortice and then quickly worked. The whole interior gives the impression of a spontaneous and freewheeling approach to violin making: the sides are marked by scratches caused by a tooth-blade plane; the blocks show the split grain; and the linings appear cut and scraped without any care for the cosmetic result.

Two Calcagno violins

Two violins by Calcagno, dated c. 1740–50 (left) and 1743 (right). Photos: Tarisio

Labels

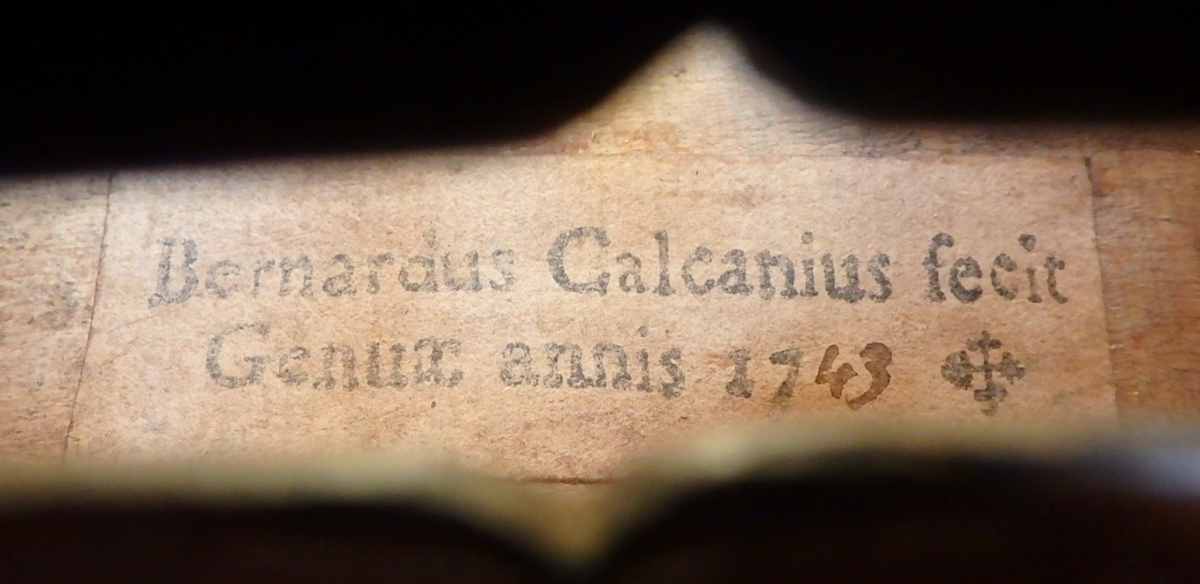

Authentic labels on Genoese instruments are quite rare today. We know that many labels were removed and substituted especially in the 19th century in order to sell instruments as the work of more famous makers, but even so is still surprising how difficult is to find good ones. A possible reason is that many of these instruments were originally sold without a label in order to avoid incurring taxes. As we saw in part 1, the Genoese economy in the mid-18th century was weak, and the working class in particular suffered under the resulting fiscal pressures. The few surviving Calcagno labels show that he used a Latin form of his name: Bernardus Calcanius, with a Greek cross in the lower right corner.

The label in the 1743 example appears to be original. Photo: Tarisio

Archings and edgework

The quality of the wood Calcagno used for his instruments can vary significantly and a substantial part of his production is made with good but not the highest-quality wood. He sometimes chose poplar wood, usually cut on the slab, for the one-piece backs of his violins and cellos. However, there is a series of instruments, particularly from the 1740s, in which we can see beautiful pieces of imported maple with deep, wide flames and tight grain. The arching is always cut with care and control; it is sometimes quite pointed on the bellies, especially where the f-holes are set closer together. The use of the scraper for finishing is always evident, particularly on the backs.

Purfling

Calcagno typically set the purfling quite close to the edges, between 3.0–3.3 mm from the outside edge. He used beech for the white parts, with a long and pronounced fleck, while the black can be walnut; the overall effect is quite peculiar, since the black is quite pale and there is low contrast between the strips. Due to oxidation, the color of the black strip has in some examples turned to a gray hue.

The purfling typically has no joint in the upper or lower bouts, as seen in the 1743 violin. Photo: Tarisio

The three strips are almost of the same width and are not always perfectly joined together, suggesting that they may have been inlayed as three separate strands and without any joint in the upper and lower bout, a typical feature of Calcagno purfling.

Corners

Calcagno’s purfling corners are short and do not have an over-extended bee-sting, although they are slightly elongated (probably deliberately) with the cut of the knife. Signs of the purfling cutter are visible in the corners, which are kept short, converging and well rounded.

The 1743 example shows the purfling corner slightly elongated with the cut of the knife. Photo: Tarisio

The scoop is delicate, quite flat and well balanced, with a classical appearance: from the chipping marks all around it is evident that Calcagno used to cut the scoop before setting the purfling.

The chipping marks around the arch reveal that Calcagno used to cut the scoop of the arching before setting the purfling, as seen on the 1743 example. Photo: Alberto Giordano

The edges are generally quite slim – between 3.2 mm on the bouts and 3.5 mm in the C-bouts, although in some violins are as narrow as 2.6 cm. The section of the borders is consequently quite oval and pointed, cut with a confident hand that has left some knife marks around the contour, especially on the back. (foto 6).

Calcagno had a confident hand and often left knife marks around the edges, shown here on the 1743 violin. Photo: Tarisio

Soundholes

Calcagno’s f-holes show great personality and are intriguingly unpredictable in design. It is difficult to come across two of his violins with exactly the same f-hole shape and it seems that he had quite a ‘del Gesù’ approach towards them. Rather than using a straight f-hole model, he appears to have used a half-model or a kind of flexible template with which he could create different outlines using the same pattern. His models can be generally divided in two: one is his personal design, which is usually quite upright and slim; the other, rounder and wider, seems inspired by Jacob Stainer’s work, which was fashionable in Italy at the time.

The marks of the scraper can be seen in the scoop of the f-hole on the 1743 violin. Photo: Alberto Giordano

The carving of the f-holes is always undertaken with great skill and confidence using a sharp knife, which Calcagno also used for the upper and lower holes. The nicks were cut with two quick strokes of the knife, and are usually quite wide and barely rounded; the scoop of the wings is carelessly cut and irregular, sometimes different between the two f-holes, and finished with a scraper; the wings are always well pointed.

The f-hole flanks appear to have been slightly chamfered before varnishing, as the 1743 violin reveals. Photo: Alberto Giordano

The flanks of the f-holes appear to have been slightly chamfered: this was caused by an abrasive action with a kind of sandpaper – perhaps some pumice powder on a rag? – before varnishing, which has also left minor scratches in other parts of the instrument.

Scroll

Calcagno’s strong personality is reflected in his scrolls, which always bear the marks of his idiosyncratic attitude. On the side view of this example one can see the peculiar elongated and swinging pegbox: large at the nut, it narrows up to the throat, which has been left opened and quite high. The scroll itself has a classical charm. It is well balanced and cut with confidence; the chamfer was cut with a chisel and then slightly rounded; the eye is quite consistent and well rounded; the chamfer is painted black, demonstrating that Calcagno was well informed about this Cremonese fashion.

The remains of the blackened chamfer is visible on the c. 1740–50 example. Photo: Tarisio

The black stain is still visible in many places on the chamfer of this scroll and it was laid at an early stage.

The c. 1740–50 violin demonstrates how the scoop of the volute turns starts quite flat then deepens towards the scroll. Photo: Tarisio

The scoop of the turns starts quite flat and then deepens towards the button. The front view shows the tapered pegbox, which narrows at the end; the ‘fan’ of the scroll; and the bold, smartly rounded chamfer.

Varnish

While many 18th-century Genoese instruments show a quite simple varnish, in Calcagno’s instruments we often see a more sophisticated one. The texture is sometimes quite thick and even rich, the colors ranging from a yellow-brown to a more orangey brown-red of good consistency. The ground is always well reflective with some penetration in the grain. The effect of this can be quite strong, as it reveals a strong oxidation of the grain, with a gray-green hue; it seems likely that Calcagno, like his slightly older contemporary Cordano, was seeking an antiqued finish for some of his instruments.

Violin maker Alberto Giordano is an expert in Genoese making and assistant curator to the Paganini ‘Cannon’ violin.

The violin dated c. 1740–50 is Lot 242 in our March London auction. The violin dated 1743 is available in our New York Private Sales department; please direct inquiries to Carlos Tome: ctome@tarisio.com.