The medieval street dedicated to Saint Mary Magdalen in Genoa has always been a working class neighborhood. Today still a crowded place in the historic center of the city, it is delimited on the north by the Strada Nuova, the aristocratic street of bankers and tycoons built in the mid-16th century, and on the south by the commercial and business core of the old town. During the 18th century the majority of the instrument makers in Genoa lived there.

At this time the economic situation in Genoa was particularly difficult, due to a long political and financial crisis. The city had been a great military and commercial power in the Middle Ages, and since the Renaissance it had been the most important financial center in Europe. Genoese bankers loaned money to kings and emperors such as Charles V, Philip II and Louis XIV among many others. But the traditional caution of the Genoese government – its strategy of neutrality, a lack of investment, the loss of business in the Mediterranean, the lack of a fleet, and allowing private interests to overrule those of the city – had all weakened the Republic of Genoa both politically and economically. As a consequence the town was humiliated by the easy invasion of the Austrian troops in 1746 after the Siege of Genoa.

Genoa engraving ‘View of the buildings on the Sea Wall’, 1769, designed by A. Giolfi, engraved by G.L. Guidotti; Collection of the Cassa di Risparmio di Genova e Imperia. Image: courtesy Alberto Giordano

In spite of all this, Genoa’s musical life was highly active during the 18th century. The Teatro del Falcone and the Teatro Sant’Agostino were thriving, thanks to the support of aristocratic patrons; meanwhile the old theater ‘delle Vigne’, founded in the 17th century, offered less sophisticated types of shows at reasonable prices. It seems that the Genoese audience was an important one, always up to date with the latest fashions and entertainments. This is the environment in which Bernardo Calcagno plied his craft as a violin maker and, a few decades later, the young Paganini started playing the violin.

Violin and guitar making had originated in Genoa during the early 17th century with the arrival of a community of German makers from the Füssen region. They were mainly guitar and lute makers – instruments that were more expensive than violins, due to the use of precious materials such as ebony, ivory, tortoiseshell and mother-of-pearl. Among this community were Cristoforo Bittig (1640–1695) and Martinus Heel (1630–1708), who worked in Genoa for many years; a few good-quality violins and a cello by these makers are known today.

Although we know nothing about Calcagno’s apprenticeship, we do know that in 1730 he was sharing a house (and probably the attached workshop) with the German maker Andreas Statler

Bernardo Calcagno [1] was born in the 1680s and is often recorded as a sonatore (a player or musician) and a paggio (a valet), employed by wealthy families. His services probably also included giving music lessons to the members of the family he was serving; this was quite a demanding role during the period, as it also involved giving dance lessons. Information about Calcagno’s life is scarce, but his career in violin making appears to have begun in the early 1730s, when he was over 40.

Although we know nothing about Calcagno’s apprenticeship, we do know that in 1730 he was sharing a house (and probably the attached workshop) with the German violin maker Andreas Statler or Stanzer [2] (1674–1732). [3] Statler claimed to be a pupil of Girolamo Amati II, according to a label on a violin of his from 1723. He was also close to Filippo Cordano (1660–1732), [4] who is considered to be the first Genoese-born violin maker active in the 18th century. Statler was the witness at Cordano’s marriage in 1707 and it seems likely that the relationship between the two makers was a long-standing one; meanwhile Calcagno’s son married Cordano’s daughter, deepening the connections between these makers. Certainly Calcagno’s work appears to have been influenced by both Statler and Cordano: their instruments share the same basic making technique and show similarities in the ground of the varnish, as well as a general taste in finishing the instrument.

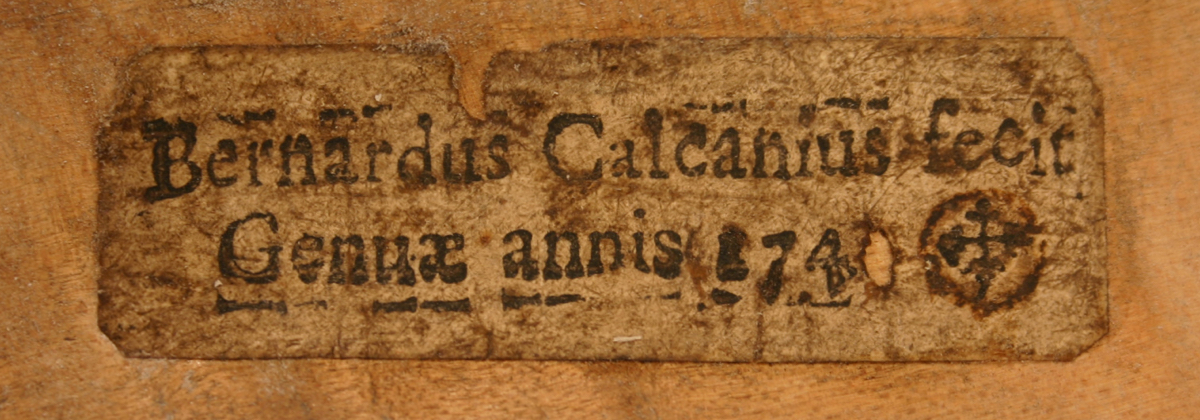

Rare example of an original label from a Calcagno violin. Photo: courtesy Alberto Giordano

Cordano and Statler both died in 1732, leaving the violin market to Calcagno, who by then was experienced enough to satisfy his customers. His output of instruments was significant: he produced not only violins and cellos, but also plucked instruments, violas d’amore and probably other instruments. The 1740s were a particularly productive time for him as the city’s senior violin maker. It is intriguing to see that the demand for musical instruments was increasing in a city experiencing financial stagnation. Yet despite this the music world was thriving, stimulated not just by the increasing activity of local theaters but also the growth of a new kind of market: that of the dilettanti, typically amateur players from the middle class, who enjoyed spending money on their musical passion.

A violin by Bernardo Calcagno, Genoa, c. 1740–50. Lot 242 in our March London auction. Photos: Tarisio

More photosThis may explain the use of fine wood that we sometimes see on Calcagno’s instruments: during times in which many instrument makers in northern Italy were using local wood for the production of cheaper instruments, Calcagno could afford to buy expensive imported maple. Presumably this was for the satisfaction of wealthy buyers, who he could have come across through his roles as valet and musician.

Calcagno died in Genoa in 1756. He appears to have been in good health almost until the end, as his production continued into his last years. Although we do not know whether he trained any pupils, it seems likely that in his final years he was assisted by a neighbor, Angelo Molia, who lived next door and whose instruments show technical and stylistic similarities to Calcagno’s work.

Thanks to Philip J. Kass, Benjamin Schroeder, Maria Rosa Moretti and Maurizio Tarrini.

In part 2, Alberto Giordano explores the characteristics of Bernardo Calcagno instruments through two different violins.

Violin maker Alberto Giordano is an expert in Genoese making and assistant curator to the Paganini ‘Cannon’ violin.

Notes

[1] Calcagno used the Latinisation ‘Calcanius’ on his labels and is often referred to as Calcani; however, his name in the contemporary records is spelt ‘Calcagno’, a typical Genoese family name that remains common today.

[2] It is difficult to find this name spelt twice in the same way in archival records: variations include Stassler, Stasser, Stanzer and Stanza.

[3] Parish records of Santa Maria Maddalena, Genoa.

[4] Curiously there are two violin makers named Jacopo Filippo Cordano recorded in the Genoa archives. The second one was active in the 1770s; it is not known if this second Cordano is from the same family, and the work of this maker is still under investigation.