What we know about Andrea Amati’s work all fundamentally flows from the marvellous ‘Charles IX’ instruments dating from around 1566. What he had achieved before, or indeed after, is hard to know since so few original labels exist, but at this time he was already 60, and had probably been assisted by his son Antonio for at least ten years (see part 1). Nine ‘Charles IX’ instruments survive, all with the motto ‘Pietate et Justitiae’ painted on the ribs. The quality and style of the decoration varies within the set, which presumably took some time and a co-operative effort to complete. There has been much discussion about the authorship of the painted decoration, and the general consensus today seems to be that it was carried out by painters’ workshops within Cremona but is insufficiently distinguished to indicate a particular master working at the time.

Andrea Amati viola from the ‘Charles IX’ set of decorated instruments, c. 1564. Photos: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

More photosThe exact circumstances of the Charles IX commission are still unknown. The first written account comes from Jean Benjamin de la Borde’s Essai sur la Musique published in Paris in 1780, which states that Charles ordered twelve large and twelve small violins, six violas and eight cellos. Of these, one full (‘large’) size violin, four small violins, one viola and three cellos exist. Only one document survives to support any of this, however, and that concerns just one violin, paid for by Charles IX through a M. Delinet in 1572, ‘to be played in the French Court’. The connection between the French court and Cremona is clear; Charles’s mother, Catherine de Medici, was a well-known patron of music and she employed the Piedmontese violinist Baldassare di Belgioioso (c. 1520–c. 1587) as a dancing master for herself and her children. Another Cremonese violinist, Girolamo Magarini, also enjoyed a professional position in the French court from 1560. [1] Any one of these people could have brought Amati to the notice of Catherine and Charles.

Portraits by François Clouet of (left) Catherine de Medici and her children (shown with her hand on the future Charles IX’s shoulder) and (right) Charles IX during his short reign

Charles’s reign was short, he died aged only 24 in 1574, and what happened to the set of Amati instruments after this is still largely a mystery. There is no record of their use during the following two centuries. The violinist J.B. Cartier, writing in 1798, claimed that the instruments had been stored in Versailles, and he personally was responsible for saving one of the violins from the revolutionary riots of 1790. [2] In around 1818 another ‘Charles IX’ violin came to the workshop of Nicolas Lupot, where it was restored and given a new label, indicating the perfectly plausible date of 1566 for the original. The collection had clearly been dispersed some time before that, however. The London violin maker John Betts lists two in his notebooks compiled around 1800. [3] One is clearly described with its label of 1564, as having been previously in the possession of the violinist Francesco Geminiani, who lived in London from 1714 until his death in 1762, except for a sojourn in Paris before 1755. Another, the ‘Tullie House’ violin, was owned by the English violinist William Corbett, who died in 1748. Today, these three violins can be found in the Museo del Violino in Cremona, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and the Tullie House Museum in Carlisle respectively.

Andrea Amati ‘Charles IX’ violin with a label dated 1564. Photos: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Another distinctive set of five decorated Amati instruments bears a different motto on the rib garland, ‘Quo unico propugnaculo stat stabique religio’ (‘by this bulwark religion stands’), which is also identified with the French royal family in the 16th century. The meaning of the motto becomes a little darker in the context of the French Wars of Religion and the horrific St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572, which took place directly after the wedding of Charles IX’s sister, Marguerite. Marguerite’s monogram ‘MVA’ appears on the back of one of the violas in this set, although this was probably applied a little later, [4] it predates her marriage in 1572, when her monogram would have changed to incorporate her married name. Three violins have decorations appropriate to Philip II of Spain, brother-in-law of Charles IX and Marguerite.

Last and most intriguing of these ‘Quo Unico’ instruments is the cut-down viola in the Paris Musée de la Musique, which is associated with the description given by Cozio of a cut-down viola originally made with five strings. [5] Renato Meucci suggests the armorials are of the young Philip II of Spain, specifically appropriate to the rank of Prince, and therefore predating his coronation in 1556. [6] If that is the case, it would indicate a very early date, significantly before the instruments of the ‘Charles IX’ set (another cut-down tenor viola, the ex-Stanley Solomon, is also proposed to belong to this earlier period due to the slightly unusual and perhaps primitive form of the soundholes, although the W.E. Hill & Sons certificate dates it to c. 1580). [7] A further half-dozen or so instruments are known without label and decorative additions, giving us a store of around 20 works by Andrea Amati, which continue to reward close study and analysis. Of these the outstanding example is the ‘Corbett, Bowles’ violin labeled 1574, one of the best preserved and purest.

A cut-down viola from the ‘Quo Unico’ set of decorated instruments. Photos: courtesy Cité de la Musique, Musée de la Musique (Paris); photo by Jean-Claude Billing

More photosThere is nothing further to anchor the ‘Quo Unico’ set chronologically, unlike those of the ‘Charles IX’ group. It is perfectly possible that they anticipate the ‘Charles IX’ instruments and provide a little more form and sense to what we might imagine about Amati’s career. In this, the main anchor points are 1526, when it seems fair to assume he was the ‘Andrea’ working as a luthier with Martinengo; 1539, when he moved in to his home in San Faustino; 1556, when his son Antonio was working with him; and the period 1564–74, which, including the 1566 cello, covers the only reliably dated works. The 1542 and 1546 instruments recorded by Sgarabotto and Cozio (see part 1) we can take only on trust.

The involvement of Antonio is intriguing, and it has been suggested that he was responsible for a large proportion of the work identified as being by Andrea

In 1526 Andrea was already 21 and by 1564 he was 59. This would normally cover the most productive period of any craftsman, and at the age of 69, as he was in 1574, we might expect him to be faltering. Of his work that I am familiar with, I would venture that the 1564 Ashmolean violin sits comfortably at the zenith of his achievement. The rest of his output can be considered either as examples of his developing maturity or declining powers, and only be somewhat randomly distributed around that central point. The involvement of his son Antonio is particularly intriguing, and it has been suggested that he was responsible for a large proportion of the work identified as being by Andrea. He was certainly active in the workshop by 1556, when he was in his mid-20s. The younger son, Girolamo, was born in 1561, too late to be involved to any serious degree with any of Andrea’s known work; he was aged only 16 when Andrea died and presumably gained most of his training from Antonio.

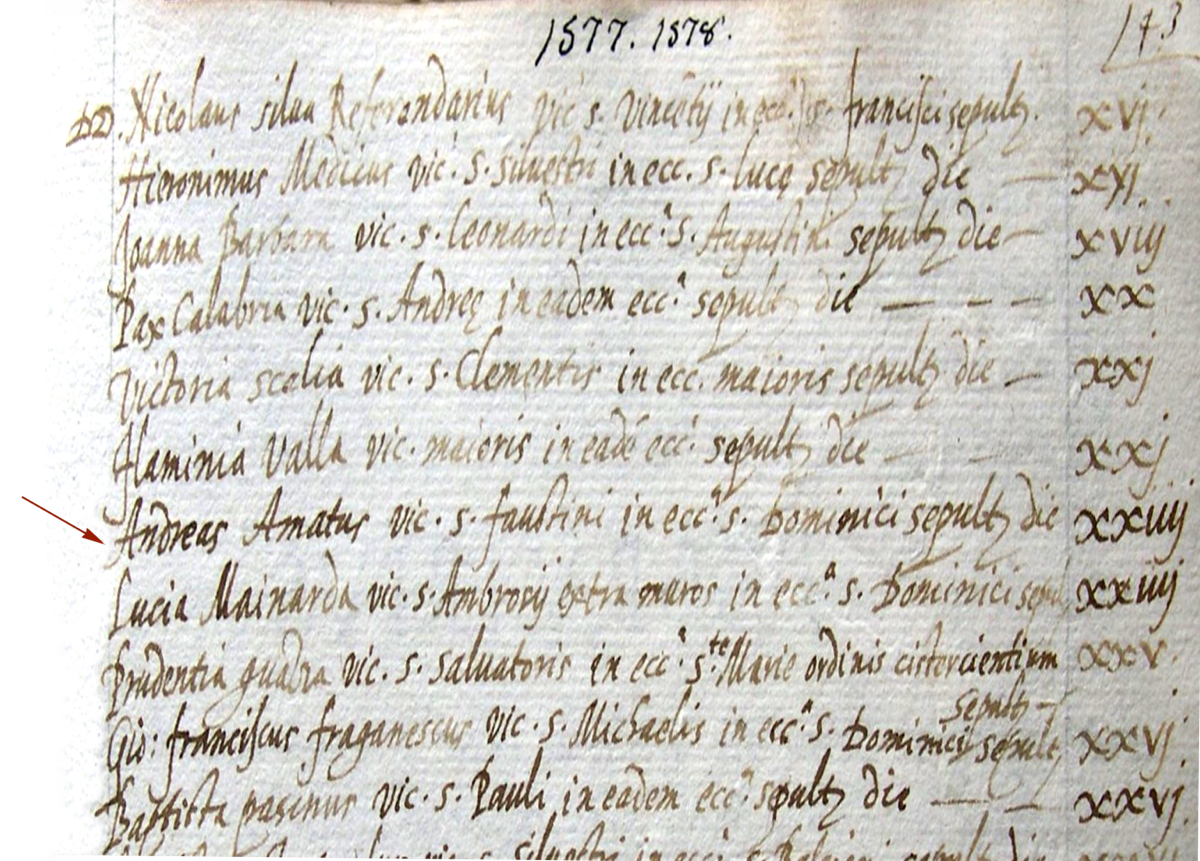

Cremona burial record from 1577. Andrea Amati is seventh on the list, which notes that he is buried in the church of San Domenico. Image: courtesy Carlo Chiesa

What stylistic changes occur throughout Andrea’s work are primarily seen in the form of the soundholes. His most characteristic model has particularly large upper eyes, large central nicks in curved form, a pronounced double curvature to the stem of the ‘f’ and short, very slender wings. All these aspects vary slightly. The central notches of the 1574 violin are noticeably smaller, and formed with two straight cuts, as they are done on instruments signed individually or jointly by the brothers Antonio and Girolamo. The most extreme form of the double curved stem and wide, rounded notches can be seen in the instruments of the ‘Quo Unico’ group and the 1564 ‘Charles IX’ violin of the Ashmolean collection.

A comparison of the ‘Quo Unico’ viola (left) and the 1574 violin f-holes suggests a development in Andrea Amati’s style – or possibly the hand of his son Antonio. Photos: left: Cité de la Musique, Musée de la Musique (Paris); photo by Jean-Claude Billing; right: National Music Museum, The University of South Dakota; photo by Byron Pillow

Nevertheless, we cannot assume that these changes indicate an intervention by the younger man, and the evidence of Antonio’s hand; they may simply show the continuing development of Andrea’s own style. If they do represent a different hand at work, it is worth keeping in mind that the 1574 violin falls outside the ‘Charles IX’ group, made (if the label is indeed correct) in the year of the king’s death and without decoration. Nothing we know necessarily detracts from the idea that the work now attributed to Andrea Amati is indeed primarily from his own hand, and that by the mid 1560s he had virtually perfected the design of the modern violin. These instruments are made in precisely the same way that Stradivari followed, some 150 years later. They were designed with a geometric precision that demanded accurate construction, using a mould to shape the ribs consistently, with linings morticed into blocks, the whole instrument entirely planned and worked with enormous attention to detail. The closely regulated and geometrically poised outline remained the template for all Amati instruments until Nicolò’s Grand Pattern, which he introduced around 1630, while still working for his father Girolamo. It remained the basis for all the work of Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ and for the innovative designs Stradivari developed in the 1690s.

Despite personal variations, every maker in Cremona used the scroll design drawn by Andrea

What is surprising is the subtlety of Andrea’s archings, which are generally lower, flatter and more Stradivari-like than the forms that Antonio and Girolamo, and especially Nicolò, developed later. It is a point worth arguing that Stradivari’s ‘Amatise’ period from 1670–90 was derived from Nicolò’s work, but his ‘golden period’ of 1700–20 owes more to Andrea. One form that remained almost constant throughout the history of Cremona’s classical period is the scroll model. Despite personal variations in the handling of the template and the carving of the spiral, every maker in Cremona used the design drawn by Andrea. One can superimpose the side-view outline of the scroll of the ‘Messiah’ over any of Andrea’s, and the thickness of a pencil line here and there is really all that separates them.

A comparison of the ‘Kurtz’ Amati (left) and ‘Messiah’ Stradivari heads

Andrea Amati founded the Cremonese tradition in its completeness of vision, design and execution, a process that separated it from all other schools of making across Europe, until students of the Amati family itself began to spread the techniques through their own movements in the late-17th century. Andrea died in 1577 aged 72, a venerable age for the period. However, it is unfair to take credit for the magnificent and game-changing ‘Charles IX’ instruments away from him out of plain ageism. His instruments are the foundation of the entire Western orchestral musical culture, and among the most important artefacts we have from this revolutionary period of art and craftsmanship.

John Dilworth is a maker, writer and expert. He has written extensively about fine instruments and their makers, and is a co-author of ‘The British Violin’, ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ and ‘The Voller Brothers’ among other books.

Read more about the Amati family: Carlo Chiesa explores the life of Nicolò Amati, grandson of Andrea

Notes

[1] Cacciatori, F. (ed.), Andrea Amati Opera Omnia; Les Violons du Roi, Cremona 2007, pp. 15–16, 33.

[2] Cartier, J.-B., L’art du Violon, Paris, 1798.

[3] Unpublished private archive.

[4] Opera Omnia, Op. cit., p. 81.

[5] Frazier, B. (ed.), Memoirs of a Violin Collector, Count Cozio di Salabue, Gateway Press, Baltimore, 2007, pp. 12, 155, 278.

[6] Opera Omnia, Op. cit., p. 37.

[7] Ibid, p. 132; Draley, D. (ed.), A Genealogy of the Amati Family of Violin Makers 1500–1740, Bonetti Cremona, 1938, Maecenas Press, 1989, p. 141.

Other Sources

Woodfield, I., The Early History of the Viol, Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Huggins, M., Gio: Paolo Maggini, His Life and Work, W.E. Hill, London, 1892.

Mosconi, A. & Witten, L., Capolavori di Andrea Amati, Cremona, 1984.

Andrews, R.E., Gasparo Bertolotti da Salo, Berkeley, 1953.

Draley, D. (ed.), A Genealogy of the Amati Family of Violin Makers 1500–1740, Bonetti, Cremona 1938, Maecenas Press, 1989.

Strocchi, G., Italia nell’Arte, Florence, 1923.