One thing we know about Andrea Amati is his name. Or at least we think we do. Actually it may have been Amadi, as he wrote on at least one of his labels. But that aside, knowing his name is no small matter. In European history before the Renaissance, there was a clear pecking order with names. We know the names of kings and queens, generals, priests and then a few poets and artists. In Chaucer, the Canterbury pilgrims are identified only by their trades, not their names. We have to come a long way in history before we learn the names of the workers who constructed and supplied the elements of everyday civilised life. We don’t know who made the flutes of the ancient Egyptians, the lyre of Apollo, King David’s harp or the trumpets of the Romans. Many of them would have been slaves. The Bible offers the only example I am aware of: the half-brothers Jubal and Tubal-Cain. Jubal, ‘the father of all musicians’, and Tubal, a blacksmith and the ‘forger of all instruments of bronze and iron’, appear in Genesis.

It took the Italian Renaissance in the 15th century to raise craftsmanship to a more exalted level, but even so, although a vast iconography of elegant and wonderously shaped instruments appear in early Renaissance painting, we have no clue who made them. Eventually names do begin to emerge, and in our field of instrument making Linarol, Ciciliano, Zanetto and others associated with Venice and Brescia appear in the mid-16th century. Andrea Amati of Cremona was among this new and rarified group.

Imagining the workshops of the earliest musical instrument makers is a challenge, and so it is even for Cremona at the beginning of the 16th century, when Amati was born. There is a wonderful engraving of Jubal’s Stall by the Antwerp artist Jan Sadeler from the second half of the 16th century, which is fascinating. [1] Like much Flemish art of the period, it shows a biblical scene in an authentically detailed contemporary context.

Jubal and his Musical Instruments, engraving by Johann Sadeler I, 1583

Jubal’s workshop is a thatched, two-storied wooden building, with the horizontally hinged shutters that seem to be characteristic of medieval shops or ‘stalls’, the lower part providing a display counter or shelf and the upper a shelter for the customers viewing the wares. Living space for Jubal’s family is an attached building to the right. An open doorway leads into what is essentially a showroom, hung with various instruments, but most of the hectic activity is taking place in the street, with three workmen and two children all stripped to the waist and laboring over lathes and saws, Jubal himself finishing a long-necked viol in the foreground. There are bagpipes and all sorts of wind and stringed instruments underway and displayed for sale. In the background, the street leading to a castle is filled with dancers and musicians enjoying the benefits of Jubal’s labor. The whole picture is crammed with activity; labor, trade, music and dancing all shown within the closed moralistic frame of industrial endeavor and its resulting pleasure.

In the Lombardy of Amati, urban architecture was mostly stone and brick, and the storied workshop would have had a tiled roof. We don’t know if Amati’s efforts extended, like Jubal’s, to making bagpipes and shawms, but it is tempting to visualise him in Jubal’s place, with his young sons Antonio and Girolamo in their breeches, toiling away. How he got to his position as the master instrument maker of Cremona is less easy to reconstruct.

There was only one man we know of in Cremona who was capable of making the instruments that these musicians required, and that was Andrea Amati

Cremona in the 16th century clearly had a strong musical tradition and produced a class of professional musicians that were employed in courts around Europe. John Maria Comey and his sons Innocent and George ‘of Cremona’ were members of Henry VIII’s band as far away as London in the 1540s, alongside other musicians from Venice and Brescia. [2] The French court also employed at least two Cremonese violinists in the same period. [3] Professional musicians required professional luthiers to provide their instruments, and took their work with them to the palaces and castles of Europe’s aristocracy. This sophisticated musical culture provided the training for Claudio Monteverdi, who was born in Cremona in 1567. There was only one man we know of in Cremona at that time who was capable of making the instruments that these musicians required, and that was Andrea Amati.

The composer Claudio Monteverdi was born in Cremona in 1567, when Andrea Amati’s career must have been at its height

Amati himself was born in about 1505, and the violin historian Carlo Chiesa has proposed that in 1526 he was living in the house of one Giovanni Leonardo da Martinengo in Cremona. [4] Martinengo is described in the census of that year as a dealer in fabrics and secondhand goods, but his two assistants in the house, one of whom was named ‘Andrea’, are called ‘liuters’ – instrument makers. How he came by his expertise is not known, but significantly he seems to have been Jewish, the son of a convert to Catholicism, and probably one of many refugees of the expulsion of Jews from Iberia in the 1490s. His title, ‘da Martinengo’ may indicate that he arrived in Cremona from Martinengo, a town not far away near Bergamo. The Cremonese viol player at the English court, George ‘de Cremona’, also identified himself on occasion as ‘de Combre de Cremona’, implying origins in Coimbra, Portugal.

There is a strong theory that the whole development of bowed string instruments in Europe sprang from the confluence of Arabic and Jewish peoples in Spain, and their shared musical and technical expertise. Musicians from Venice and Brescia also shared names from Jewish tradition, Cossin (or Gershon), Lupo and Kellim. These names all functioned as passports or identity cards, labeling the individuals as aliens. Amati is by this reasoning identified as a native of Cremona. His name, like Mozart’s middle name Amadeus, is translatable as ‘loved by God’ and, as is revealed in other documents, [5] he was the son of Gottardo (incidentally a Germanic name evoking the ‘strength of God’) of the parish of Sant’Elena. Clearly, we can learn a great deal from names and as more names of craftsmen emerge during this period, they begin to color and shape how we understand it.

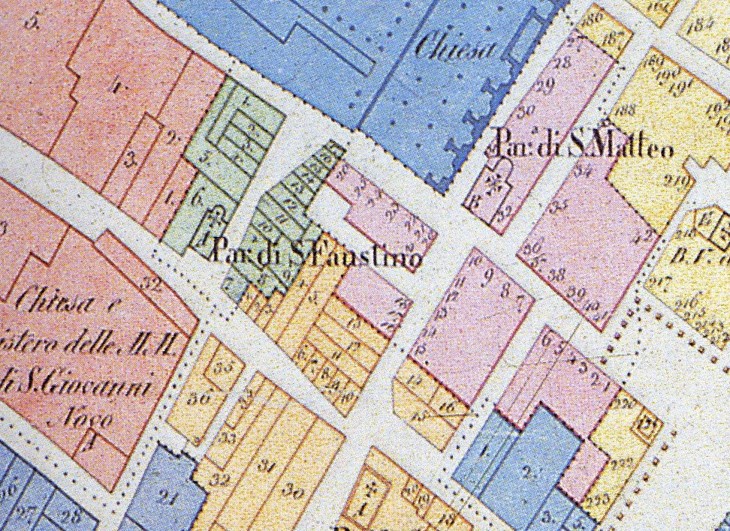

The parish of San Faustino, map of Cremona from c. 1750. The exact location of the Casa Amati is unknown. Image: courtesy Carlo Chiesa

Amati’s ‘Stall’ was the house in the parish of San Faustino that became home to four generations of Amati violin makers, spanning the entire classical period of violin making in Cremona. Andrea is known to have begun renting the property in 1539. At about this time his eldest son, Antonio, was born and Andrea was recorded as a self-supporting ‘Maestro’ of his trade. The only evidence of his activity in this period is documentary; nothing of his early work is known to survive.

Amati’s ‘Stall’ was the house in the parish of San Faustino that became home to four generations of Amati violin makers

Cozio di Salabue, however, noted in 1861 a three-stringed violin of ‘extraordinary model’ dated 1546, [6] and Gaetano Sgarabotto reported another three-stringed violin to Giuseppe Strocchi, labeled 1542. [7] Cozio’s description of his three-stringed instrument is not encouraging: ‘… the workmanship was not done well… purfling poorly executed. Only the top was made by Andrea Amati’, and in another reference, the date ‘looks like it was written in the sixteenth century’. Yet by 1556, according to the census, Amati’s son Antonio was working with him as a luthier and the trade at ‘Amati’s Stall’ would have been in full swing.

A sort of chronological denial existed among early writers about the violin, who saw the primitive qualities in Brescian work as proof of their prototypical status and, although acknowledging Amati’s seniority, saw in the sophistication of his work a development of what they assumed must have gone before. Gaspar ‘da Salò’ – again, his family name of Bertolotti was subsumed into his identity as an outsider when he moved from Salò to Brescia – was generally seen as the earliest violin maker, based on the inconsistent and apparently unrefined nature of his instruments, and possibly the fact that the Brescian makers never dated their work. Lacking proper archival information, early writers relied on speculation. George Hart says that Gasparo worked from 1550–1612; Fetis says 1560–1610. We now know that his career in Brescia did not begin until about 1563. [8] Amati’s career began before that, as early as 1539. Fetis acknowledged that Amati was born in the first 20 years of the 16th century, but suggests he may have been apprenticed in Brescia. [9] Hart even believed that Amati may have served his apprenticeship with Gaspar. [10]

The ‘Corbett, Bowles’ violin by Andrea Amati, Cremona, 1574. Photos: National Music Museum, The University of South Dakota, Byron Pillow, photographer

More photosThe Hills at first subscribed to these views. Their earliest literary ventures were contributions to Lady Huggins’s Life of Maggini, which they published in 1892, and preparation for their own unpublished volume on Gaspar ‘da Salò’. Both these works are reticent about Andrea Amati. In their life of Stradivari published in 1902 he is scarcely mentioned and only as having constructed cellos contemporary and comparable with those of Maggini. [11]

Although the Hills were familiar with the ‘King’ cello, which resided in England from 1812 to 1967, the Andrea Amati instruments that are now the cornerstone of the Ashmolean Museum collection came into their possession only later, and seem to have sparked a delayed appreciation. Arthur Hill encountered the Amati violin labeled 1574 in 1894 (the ‘Corbett, Bowles’, now part of the Shrine to Music collection), and seems to have begun his research with a letter to the historian Giovanni Livi in 1899. [12] By 1917 he was able to acknowledge the instrument, in unpublished documents, as ‘one of the most remarkable violins in existence… Much in advance of Gaspar and Maggini, who actually come after.’ Hill was confident that the label was genuine, and its unique handwritten form using red ink and Roman numerals was without precedent to his knowledge. The only extant instruments that do provide a reliable date for Amati’s work are the violin of the Ashmolean Museum, which has what appears to be an original label of 1564, and the ‘Berger’ cello, which incorporates the date 1566 in its decorative painting.

In part 2 John Dilworth discusses the surviving instruments by Andrea Amati and whether some were made by his eldest son, Antonio.

John Dilworth is a maker, writer and expert. He has written extensively about fine instruments and their makers, and is a co-author of ‘The British Violin’, ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ and ‘The Voller Brothers’ among other books.

Notes

[1] Jan (Johann) Sadeler, Stall of Jubal, 1583, Bibliotheque Nationale de France.

[2] Holman, P., Four and Twenty Fiddlers, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1993, pp. 83–88.

[3] Cacciatori, F. (ed.), Andrea Amati Opera Omnia; Les Violons du Roi, Cremona 2007, pp. 15–16.

[4] Opera Omnia, Op. cit., p. 13; Milnes, J. (ed.), Musical Instruments in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford Musical Instrument Publishing, 2011, p. 364.

[5] Musical Instruments in the Ashmolean Museum, Op. cit., p. 364.

[6] Frazier, B. (ed.), Memoirs of a Violin Collector, Count Cozio di Salabue, Gateway Press, Baltimore, 2007, pp. 14, 18, 35, 224, 241–2.

[7] Cited in Musical Instruments in the Ashmolean Museum, Op. cit., p. 364.

[8] Musical Instruments in the Ashmolean Museum, Op. cit., p. 366; Andrews, R. E., Gasparo Bertolotti da Salo, Berkeley, 1953, p. 48.

[9] Fetis, F.J., Anthony Stradivari, Celebrated Violin Maker, Reeves, London, 1864, p. 51.

[10] Hart, G., The Violin; its Famous Makers and their Imitators, London, 1875, p. 42.

[11] Hill, W.H., A.F & A.E., Antonio Stradivari, His Life and Work,W.E. Hill, London, 1902, p. 110.

[12] Giovanni Livi was author of Gasparo da Salo, 1891 and I liutai Bresciani, 1896.