Prior to the 18th century, there was no real industry of violin restorers and repairers. If an instrument was damaged — such as a broken head or a crack to the front — a violin maker was more likely to replace that part than repair it. Today, modern restorers go to great lengths to preserve historical instruments, but there didn’t used to be much incentive to restore damaged instruments, especially because long-lasting restoration techniques, like patch fitting and neck grafts, had not yet been developed. This, we can imagine, is likely what happened to the ‘Salabue, Matsuda’ …

The front and back plates of the ‘Salabue’ match perfectly in terms of dimensions, curves and outline. But because Stradivari’s style of corners, edges and purfling changed so significantly over these fifty years, the edges appear much bolder and wider on the top and the corners appear finer and narrower on the back. The edges of both the back and top are original and undoubled. The consistent edge margins corroborate the conclusion that the top was made to fit the ribs.

The ‘Salabue’ was made in c. 1666 by Stradivari at the start of this career. It is one of the best preserved examples of the maker’s early work and shows the extraordinary talent and bold style of the young maker in his early twenties. The violin is comparable to the ‘Aranyi’, the ‘Back’, the ‘Sachs’ and the ‘Canadian’. The rib outline fits on the maker’s ‘S’ mould (MS2), which Stradivari frequently used during this period of his career. But what makes this violin important is that its front was remade by Stradivari a half-century later, around 1716, at the height of his Golden Period.

The back of the ‘Salabue’ (right) twins nicely with the ‘Back’ (left) and ‘Aranyi’. All are from the period 1665-1667.

There have been countless books and articles written about Stradivari but we know surprisingly little about the early life of the world’s most famous violin maker. Where and when was he born? Who was his teacher? Who were his first clients? What we know about Stradivari begins not with his birth but in 1667, when he suddenly appears in archival records as an independent violin maker and rents a house with an attached workshop. He quickly made a name for himself and by the 1680s was already arguably the most important maker in Cremona, receiving important commissions from royalty and noble households. By the time of his Golden Period — roughly the first two decades of the 18th century — he had vanquished all competition.

The purfling on the front is considerably wider and the corners of the back are more narrow and slender.

Stradivari’s career spanned over seventy years, a phenomenal accomplishment for an artist of any age. His style changed greatly over the course of his career and although his extensive production is marked by innovation, there is a consistency of quality and character throughout. Stradivari’s early work has delicate corners, narrow edge margins, fine purfling, an amatisé arching and slender soundholes. The later instruments have a flatter arch, thicker edgework, wider purfling and sturdy, generous soundholes. There are other differences with regards to dimensions, materials and varnish but, by and large, experts can easily recognise the significant periods in his career. The front of the ‘Salabue’ is an exceptionally fine example of Stradivari’s Golden Period work. Of those that I know personally, the ‘Salabue’ reminds me of the 1716 ‘Cessole’, the 1716 ‘Medici, Tuscan’, the 1717 ‘Tyrell’, the c. 1719 ‘MacDonald’ viola.

The sound-holes of the ‘Salabue’ (right) are made in the maker’s mature style, but the original sound-holes would have looked like the ‘Back’ Stradivari of c. 1665-1670. Notice the slender stems on the ‘Back’ and the breadth, poise and sturdiness of the ‘Salabue’. Note also the narrow distance between the sound-holes and the ‘Salabue’ edge: the maker’s 1716 sound-hole was actually too wide for this model and so the sound-hole appears much closer to the edge than we would expect for Stradivari.

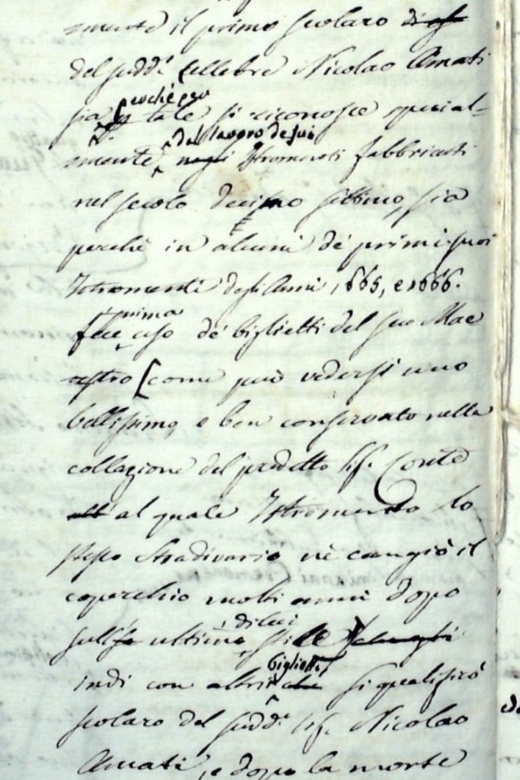

That the front of the ‘Salabue’ was made later than the back was apparent to its first known owner, Count Ignazio Alessandro Cozio di Salabue, from whom it takes its name. Count Cozio was the first great connoisseur and collector of Italian instruments. He lived in Piemonte from 1755 to 1840 and was deeply passionate about instruments and instrument makers. His memoirs and correspondence, which we refer to as his Carteggio, are among the earliest and most important sources of information on classical instrument makers and instruments. Cozio mentions the ‘Salabue’ in his Carteggio on 22 January 1823 in a passage discussing Stradivari’s training. Like most of Cozio’s writing, this passage meanders in a stream of consciousness and is overly formal (he refers to himself in the third person as ‘il Signor Conte’…). Here is the rough translation: “Stradivari was undoubtedly a pupil of Nicolo Amati because his instruments from the 17th century follow the Amati style and are often labeled Amati, in fact, [I] have one beautiful and well preserved violin by Stradivari from the year 1666 in [my] collection where the front was changed by Stradivari himself many years later in his later style.”[1][2]

Cozio mentions the ‘Salabue, Matsuda’ in his Carteggio on 22 January 1823 “… [I] have one beautiful and well preserved violin by Stradivari from the year 1666 in [my] collection where the front was changed by Stradivari himself many years later in his later style.”

…the ‘Salabue’ is not a composite in the usual sense of the word: the front didn’t come from another instrument, it was deliberately and specifically made by Stradivari for this violin.