In the 19th century Paris was swept by a craze for old Italian instruments. However, then, as now, not everyone could afford an original Stradivari or Guarneri. Jean Baptiste Vuillaume, who arrived in the city around 1818, was a talented businessman and one of the first violin makers to capitalize on the idea of making new instruments that look like old masters.

Vuillaume made over 3,000 instruments during a half-century of activity but, of these, how many were cellos? No comprehensive records exist and neither Roger Millant’s 1972 monograph nor Sylvette Milliot’s more recent research answer this question specifically. Millant reconstructed a table matching inventory numbers to production years from data that he had compiled from his colleagues in France, the UK, the US and Switzerland, but he gave no indication of the proportion of violins, violas and cellos that made up the total Vuillaume output. [1]

One simple way to approximate the number of cellos produced by Vuillaume is to use sample data from sale and archive sources, identify what percentage are cellos and then extrapolate from the Millant totals. A quick survey indicates that approximately 12% of the total instruments that he produced were cellos (5.4% were violas). This would mean that the Vuillaume workshop produced nearly 400 cellos (over 170 violas), much more than the total production of most makers. [2] (See full table below.) But, given Vuillaume’s significant cello output and his history of experimentation and innovation, it is peculiar how little variation there is in his cellos. Even though his business traded in the various 17th- and 18th-century master cello makers from Cremona, Milan, Venice and elsewhere in Italy, there is no record of Vuillaume making new cellos on any model except that of Stradivari. This is significant considering the diversity of models that he used for violin.

Given Vuillaume’s significant cello output and his history of experimentation and innovation, it is peculiar how little variation there is in his cellos

In the 1820s Vuillaume made cellos that were generically Stradivarian along the lines of those being made by Lupot, Lété and Gand but not necessarily copies of specific instruments. There were a number of notable Stradivari cellos which Vuillaume sold or serviced including the 1701 ‘Servais’, the 1707 ‘Countess of Stanlein’, the 1707 ‘Fau, Castelbarco’, the 1711 ‘Duport’ and the 1713 ‘Bass of Spain’ but only two of these became models for his new cello making, the ‘Servais’ of which he made a very small number of copies and the ‘Duport’ which was by far his model of choice.

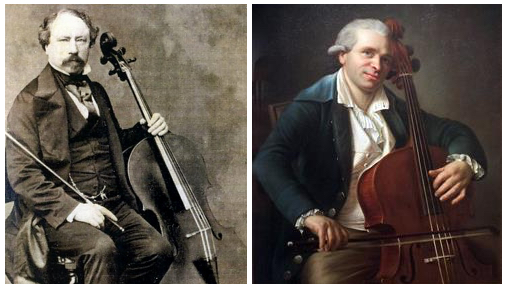

Adrien-François Servais (left) and Jean-Louis Duport (right). Images: Wikipedia Commons

The 1701 ‘Servais’ is the last and arguably the finest of the large-model Stradivari cellos. In the early 19th century it belonged to a well-known Parisian amateur, Jean-Marie Raoul, who died in 1837. Four years later, Vuillaume sold Raoul’s cello for 12,000 French francs [3][4] to a patron for the use of the Belgian cellist Adrien-François Servais. The cello left Paris in 1841 and after it arrived in Belgium it became the favored model of Vuillaume’s younger brother, Nicolas-François, who was based in Brussels. Five out of six cellos made by N.F. Vuillaume are copies of the longer-pattern cello. [5]

Two of the most influential musicians in Paris at the turn of the 19th century were the cellist brothers Jean-Louis and Jean-Pierre Duport. It is doubtful that Vuillaume would have known them, as he arrived in Paris around 1818 and the brothers died in 1818 and 1819 respectively, but their influence over Parisian musical culture persisted long into the 19th and 20th centuries.

The 1711 ‘Duport’ as it appeared in W.E. Hill’s Stradivari 1902 monograph

The 1711 Stradivari cello belonging to the younger brother, Jean-Louis, was a shrewd choice as a model for Vuillaume and after 1835 his cello making followed the ‘Duport’ almost exclusively. Fétis noted in 1834 that the first ‘Duport’ copy was made for the Exhibition Fair of 1834 [6] but there are a handful of cellos dating from 1828–30 made on the same model, with more or less the same antiquing and simulated wear patterns.

Vuillaume’s association with the ‘Duport’ Stradivari and his production of ‘Duport’ copies continued for the rest of his career. When Jean-Louis Duport died in 1819 the cello passed to his son, who was also a cellist but lost interest in playing professionally and became involved in the construction of pianofortes. [7] In 1842 the cello was sold, on the advice of Vuillaume, to the cellist August-Joseph Franchomme, who was a close colleague of Vuillaume’s son-in-law Delphin Alard, for the record sum of 22,000 French francs, nearly double the price that the ‘Servais’ had sold for a year earlier. [8] With the ‘Duport’ settled in Paris, and being no doubt satisfied at having placed it in the hands of Franchomme, Vuillaume made it his model of choice for the next three decades.

Into the 21st century this paradigm continues – makers copy the instruments they look after and those that live locally. Nicolas François copied the ‘Servais’ and Jean Baptiste copied the ‘Duport’. Today makers in New York copy the ‘Titian’ and the ‘Plowden’ and all of Cremona copies the ‘Cremonese’.

Lot 27 in our October auction: one of Vuillaume’s finest interpretations of the ‘Duport’

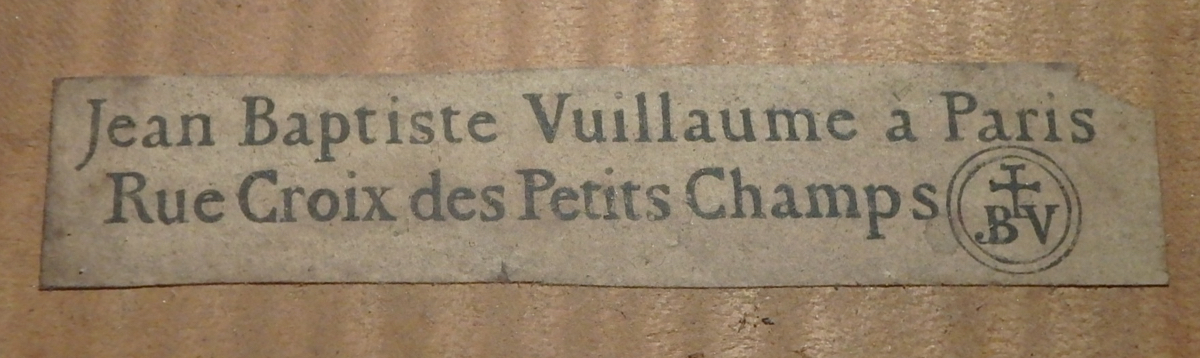

Lot 27 in our October London auction is one of Vuillaume’s finest interpretations of the ‘Duport’. When W.E. Hill & Sons sold this cello in 1928 they dated it to c. 1860 but a more accurate assessment is 1845–50. The original and undisturbed label is the type used from 1842–58 and stylistically the cello is a close match to Vuillaume’s work from the period 1845–50. In 1858 Vuillaume moved his workshop to another part of Paris to avoid excise duty and lower his costs and thereafter his labels indicated his new address of 3 rue Demours, Ternes.

The original label. Vuillaume used this label format and wording from 1842–58.

The spruce front of this cello has exceptionally wide and irregular grain, with a distance of 7 mm between the annual rings at their widest. The transition between the dark and light grains is a wide gradient more like pine and less like high-altitude spruce. There is good indication that Vuillaume thought this wood was particularly well suited for the making of cellos because he used it almost exclusively for the cellos he produced between 1845–55.

Four cello tops from 1845–55 made from the same wide irregular grained spruce

The traditional method of joining two matched pieces of spruce to make the front of an instrument means that the wood at the center of the instrument comes from the outside of the tree and the wood at the flanks of the instrument comes from toward the middle. This typically results in the annual rings at the center being closer together and those at the flanks more widely spaced. Because of the irregular grain on the front of this cello it appears that the orientation was reversed but in fact the direction of growth is normal. The cellist Jan Vogler pointed out to us that the unusual grain orientation on this cello is the same on his 1707 ‘Castelbarco, Fau’ Stradivari, which was also known to Vuillaume.

The grain is wider at the center than at the edges on the 1707 ‘Castelbarco, Fau’ Stradivari

The back of this instrument is made in two pieces of maple with attractive narrow flame ascending from the center joint, the opposite orientation to the back of the ‘Duport’. The arching is low and flat with negligible scoop into the edges. A small ridge defines the edge at three-quarters of the margin from the purfling to the outline. The edgework is clean but not crisp. The purfling is narrow with fine dark blacks and even whites. The edges are rounded gently and the corners have had their sharpest angles softened. The overall effect of the edgework is more that of an 18th-century than a 19th-century instrument. The work is clean but nowhere is it too sharp, too sterile or overly precise, the symptoms from which many French instruments in the early 20th century suffered.

The edgework is clean but not crisp. A small ridge defines the edge at three-quarters of the margin from the purfling to the outline

The ribs are of a similar maple to the back but with deeper and wider flame. The corner mitres are cut like those of Stradivari and blackened for effect. Interestingly, the ribs of Vuillaume cellos are rarely as severely cracked or deformed as those of their 18th-century inspirations.

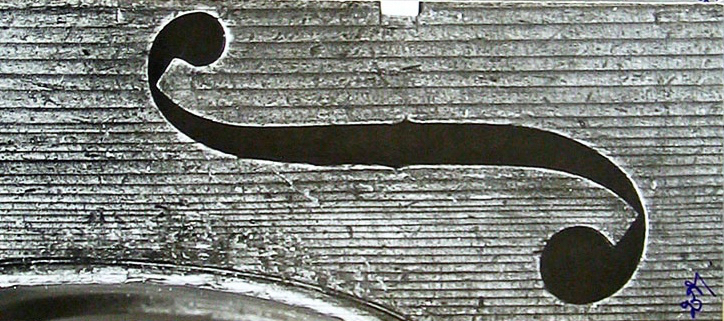

The heads of Vuillaume’s cellos are strong and predictable

The heads of Vuillaume’s cellos are visually strong and thoroughly predictable. The angle of the cheek-step is slightly obtuse; a long slender pegbox terminates into a modest throat; a large eye sits at the center of the volute; the wide, blackened chamfer is antiqued and shaded; the blacking in the fluting of the volute is slightly overdone, but adds contrast and builds visual effectiveness.

The varnish application and the careful antiquing by which Vuillaume and his workers made their new instruments look old were among the most advanced techniques of their time. In England a few early makers had taken to antiquing instruments to look like classic Italians but the major wave of copyists and imitators had yet to appear across Europe. In early 19th-century France, Lupot, Lété and Gand made good copies of generic Stradivari models, but Vuillaume’s treatment of the surface preparation and varnish distressing were far ahead of his time. The areas which received the greatest attention were the upper bass shoulders, the central back and the treble shoulders of the top.

This cello is exceptionally well preserved, with unpolished varnish and no soundpost patch or crack to the front or back. The label is the original and shows no signs of being tampered with or moved. In 1924 the instrument was sold by W.E. Hill & Sons to Leo Smith of Toronto for £170. The cello is consigned to our October auction by the family of its most recent owner, a long-serving member of a major North American orchestra who owned the cello for over fifty years.

This Vuillaume cello is Lot 27 in our October London auction. View the full catalog.

Notes

[1] Millant, Roger, J.B. Vuillaume, Sa Vie et son Oeuvre, 1972, pp. 103–104.

[2] The highest inventory number Millant cites is 3,011, but he and others note that there were instruments which left the workshop without an inventory number and the actual count is slightly higher. We have chosen 3,200 for the purposes of estimation.

[3] The Strad, September 2004, p. 922.

[4] W.E. Hill & Sons, Op. cit., p. 129.

[5] Cozio archive.

[6] Milliot, Sylvette, History of the Parisian violin making, Tome III, Book 2, p. 299 (quoting Fétis, Revue musicale, June 8, 1834).

[7] W.E. Hill & Sons, Antonio Stradivari: His Life & Work, 1902, p. 131.

[8] Ibid, p. 132.

How many violins, violas and cellos did Vuillaume make?

The proportion of Vuillaume instruments from three data sources:

a) the Cozio archive; b) aggregated auction results (1805–2019); c) the W.E. Hill & Sons business records (1861–1988)

|