In part 2 we looked at the Guadagnini dynasty, which dominated Turin violin making during the 18th century. In the 19th century this began to change as talented rivals arrived in the city.

Post Napoleonic era (1814–1860)

Once the French left Turin in 1814 the previous regime came back into power, and the French maker Nicolas Lete-Pillement, who had established his workshop just outside the old city walls, temporarily had to leave the city. Perhaps in order to continue workshop activity, or simply in his absence, an Italian employee seems to have taken charge of the operation. This was Giovanni Francesco Pressenda (1777–1854), who arrived in Turin in the 1810s and learned the trade in the Lete workshop. After Lete’s death in 1819 he re-established the business within the city limits and became the most prominent violin maker in the city for the next 30 years. Pressenda quickly gained the patronage of both Giovanni Battista Polledro, the director of Royal Music, and Polledro’s successor Giuseppe Ghebart, thus guaranteeing his success.

Pressenda violins from 1838 (left) and 1827; his instruments have a distinctive family resemblance thanks to his careful oversight in the workshop

Unlike the Guadagninis, his only serious rivals in those years (see part 2, the Guadagnini family), Pressenda concentrated primarily on violins; the vast majority of his output consists of them, along with a small quantity of violas and cellos. Like the Guadagninis, he employed a number of people to work for him, and the list of those who can be traced to his workshop contains almost exclusively French names. Not surprisingly, his work followed the French system of construction then being practised in Mirecourt: external molds based on those of Mirecourt, and fine details in keeping with Mirecourt traditions, but with a soft, supple and deep red oil-based varnish unlike any in use by other makers at the time.

Pressendas from throughout his career look unmistakably like Pressendas, even though there are some decided changes over the years

However, Pressenda’s instruments are particularly distinctive for the consistency of their family resemblance. The wood selection, finish, varnish and the small details of purfling and edge and corner work all show his oversight on what were no doubt unfinished works by his employees. As a result, Pressendas from throughout his career look unmistakably like Pressendas, even though there are some decided changes over the years in all of these particulars. The deep plum-red varnish seems always to have been applied without sealers, so that it stains the spruce but gives dramatic reflectivity to the maple. Like Stradivari and Guarneri, he always marked out the scroll edges in black.

Among Pressenda’s French employees were Joseph Calot, Leopold Noiriel and Pierre Pacherele. Calot’s activity in Turin was during the 1820s, while Noiriel, who is best known for some excellent basses, seems to have worked for a variety of local instrument builders; these included the Denis family, who were makers of serinettes but vendors of all manner of instruments, and the Vinatieri family, who were makers of woodwind instruments. Pressenda’s longest-serving employee was Pacherele, who arrived in Turin in the 1820s and remained there, on and off, until the late 1830s, by which time he had settled in Nice. However, even after that move Pacherele’s hand remains present, and in Pressenda’s late years more visible, suggesting that he continued sending unfinished instruments to Pressenda. Pacherele was also married to one of the Denis daughters and presumably made occasional visits to Turin as a result.

Giuseppe Rocca violin from 1850, shortly before he moved from Turin to Genoa in an attempt to revive his flagging fortunes

More photosPressenda’s most famous employee, though, was another Piedmontese: Giuseppe Rocca (1807–1865). Rocca was from the same region south of Turin, the area called the Langhe, as Pressenda. Rocca determined to pursue violin making in Turin in the late 1830s and by 1837 had opened a shop there. However, misfortune and illness drove him into financial crisis, which may have been the reason for his employment by Pressenda. Once his finances recovered he set up on his own again around 1842, but he never met with the success he yearned for. In 1851, after the death of his third wife, he moved to Genoa, where his work had received plaudits in the local exposition in 1846. Still success eluded him, and in his absence both Pressenda and Gaetano Guadagnini II died, creating a great but unrealized opportunity. In 1857 Rocca returned to Turin, which by now was dominated by the young Antonio Guadagnini. After several fitful years he returned to Genoa in 1862. By this time, his resources and opportunities gone, he entered a precipitous decline, moving three times in his last few years in ever humbler circumstances, and finally drowned in a well outside the city walls in 1865. So poor were his prospects that none of his sons followed his profession, the youngest, Enrico, returning to the craft only in the 1880s, and then initially as a mandolin maker.

There were some other active makers in the city during these years, both of them amateurs. Both Pressenda and the young Gaetano Guadagnini II provided assistance to a local amateur, Alexandre D’Espine (1777–1855). From a noble Piedmontese family and the Royal Dentist by profession, D’Espine was also an avid and talented amateur. He worked primarily during the 1820s and 1830s and had given it up by the time he moved to Pinerolo in 1851. Lastly, there exists documentary evidence (and one violin that I encountered decades ago) of a minor nobleman named Giorgio Gondolo, who made a Guadagnini-inspired violin that he entered in competition in 1884.

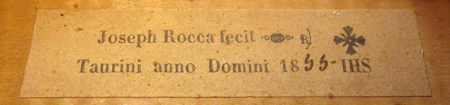

Rocca label from an 1855 instrument

During this period Turin hosted expositions in 1829, 1832, 1838, 1844, 1850 and 1858. Most of the city’s major makers entered these and were awarded prizes. Pressenda was the most consistent winner, receiving first copper and then silver medals, the highest such awards granted to violin makers. Rocca always received copper medals, as did Gaetano Guadagnini II, whereas Antonio Guadagnini received a silver medal on his first outing in 1858. D’Espine entered in 1829 and received a copper medal.

Post Risorgimento (1860–1900)

By the time of Italian Unification at the end of the war with Austria in 1859, Pressenda had died and Rocca had settled in Genoa, and Gaetano Guadagnini’s son Antonio was now running the most successful instrument making shop in Turin. His rival, Teobaldo Rinaldi, was a native of Alba and apparently a friend of both Pressenda and Rocca. He settled in Turin in 1855 and by 1859 was working as a violin dealer in that city. Rinaldi’s daughter married yet another man from the Alba region, Benedetto Gioffredo (1821–1886), who was able to succeed to the business by taking on his father-in-law’s family name and was thereafter known as Gioffredo Rinaldi. Under his stewardship the business regained its former prominence. These two shops led the trade in the city until the late 1880s.

Both Guadagnini and Rinaldi employed others to work for them. The best known of these today are Enrico Marchetti (1855–1930), the Melegari brothers and Maurice Mermillot, a French luthier, native to the Savoie but trained in Mirecourt, who worked for Guadagnini for some years before returning to Paris and his own successful venture.

By the time of Italian Unification, Pressenda had died, Rocca had settled in Genoa and Antonio Guadagnini was running the most successful instrument making shop in Turin

The brothers Enrico (1835–1895) and Pietro (1842–1874) Melegari were natives of Parma who had studied woodworking and music in childhood but did not initially engage in violin making. During the 1860s they worked in the Arsenale in Genoa; these were the same years in which Enrico Rocca worked there, so it is not impossible that they knew one another. They supposedly worked for Antonio Guadagnini briefly before opening their own shop in 1870. Pietro died young and Enrico continued on his own, receiving plaudits at international competitions for his distinctive and idiosyncratic work. He died in 1895 without a successor.

Melegari instruments are very recognizable for their curious small scrolls, their deep red to orange varnish of often very soft texture, and their unusual arching system, in which they are often left very thick along the strip running down the center. They are often branded with the maker’s name in capital letters. The violins and occasional viola and cello are mostly Enrico’s personal work, for although the early instruments have the Fratelli Melegari label, Pietro is believed to have engaged primarily in guitar making in the Guadagnini manner.

Enrico Marchetti viola c. 1880; he was employed by both the Rinaldi and Guadagnini shops before setting up independently

More photosEnrico Marchetti was a native of Milan. He had worked for Luigi Bajoni there before moving to Turin and entering service first with Rinaldi and then with Antonio Guadagnini, with whom he worked for five years. He opened his own shop in 1881, not long before the death of Antonio, and went on to build a successful career, of which more will be written in the next part of this series, concerning the 20th century.

Gioffredo Rinaldi also employed Marchetti as well as, during the 1880s, the young Carlo Giuseppe Oddone. However, Rinaldi’s successor was Romano Marengo (1866–1926), known as Marengo Rinaldi, who assumed control of the shop in 1886 and continued it until his own death in 1926. Like Gioffredo Rinaldi, Marengo Rinaldi worked primarily as a dealer, making a small number of instruments for his own account. These included an interesting quartet, submitted to the Paris Exposition of 1900, where it received a gold medal.

One cannot leave the Rinaldis without mentioning their contribution to our understanding of the Turin violin makers. Gioffredo Rinaldi published the first biography of Pressenda at the time of his entry into the Vienna Exposition of 1873. Marengo Rinaldi extended this effort to further promote Pressenda’s (and his own) role in the history of violin making. His 1904 book Tre Figlie della Langhe gave accounts of both Pressenda’s and Rocca’s lives; in Rocca’s case it was the first time his life had been set down in print. All of our understanding of these makers began with these two publications.

Philip J. Kass is an expert on classical violin making and has contributed extensively to the Journal of the Violin Society of America, The Strad magazine and the New Grove Dictionary of Music. In the final part of his Turin survey he looks at the city’s 20th-century makers, including Oddone and Fagnola.