Violin making in Piedmont progressed along similar lines to its development in other parts of Italy, but with a decidedly different set of influences. Piedmont, under the rule of the House of Savoy, was very much a satellite to the French court, with numerous blood ties to the House of Bourbon. Indeed, the king of France had long had designs on annexing that territory, and avoiding that fate significantly determined the actions of the court in Turin. Furthermore, Piedmont also represented a buffer state between the rival empires of France and Spain, which controlled Cremona and all of Lombardy.

The earliest musical instrument makers in Turin were German émigrés from the Tyrol, who began arriving in the city, and many other places around Italy, during the Thirty Years War (1618–48). They principally made lutes and, as the century progressed, guitars, and they were identified by the term chittarieri. In the 1640s after the death of the reigning duke of Savoy, his wife, Christine Marie, who was also the daughter of Henri IV of France, became regent, and during her reign imported a great deal of the culture she had known while growing up in Paris, including dancers and musicians. It is my belief that these musicians brought the earliest violins into the court; not instruments from Cremona, but rather from Paris and the Low Countries, from where most French musicians were then acquiring their instruments. These Franco–Flemish violins served as the model for what would soon be created in Turin.

A late-17th-century Cattenar violin. His violins follow the proportions of the small-pattern Brothers Amati. Photos: Daniel Lane, Tarisio

More photosThe earliest chittarieri known to have made violins in Turin were Henricus Cattenar (c.1620–1701), Fabrizio Senta (1629–1681) and Andrea Gatto (active 1660s). Cattenar was a native of Franconia in the Holy Roman Empire, while Senta and Gatto were natives of Piedmont. Little of their work survives today, but the earliest instruments reveal a strongly Flemish construction system, familiar also to the makers of the German states, which included ribs inset into channels in the back and one-piece necks and top blocks glued to an extended platform. It is a system that a maker trained in lute and guitar construction might adopt for the purpose of reproducing a Flemish violin. This method, with minor adjustments, remained the standard for violin construction in Turin until the arrival of G.B. Guadagnini in 1771.

Cattenar (as he was always called, never Cattenari) was the most active of these early makers, given his long lifespan. His shop was located in the section of the city where most musical instrument makers lived, between the Piazza San Carlo and the piazza today known as the Piazza Reale. We do not know the identities of his pupils and there is a gap following his death during which time there was no documented violin maker in Turin. This does raise the possibility that there might be truth in the old and unsubstantiated rumor that his youngest son, Giovanni Francesco Cattenar, a bass player in the Court Ensemble, might also have been a violin maker. There exist no instruments that might yield any clues.

Cattenar’s earliest documented instrument, a viola of 1661 (ID 47581) now in the collection of the Royal College of Music in London, is in some ways a prime example of the early hybrid between the northern European styles (particularly in its construction) and those of the Italians. By the later 1670s his work had adopted a Cremonese style. His finest instruments have a decided Amati flair to them, but with some subtle differences. They follow the proportions of the small-pattern Brothers Amati but with a firmer varnish and a sense of rigidity in the placement of the ‘f’s: slanted but with very straight stems. He also adopts something like the Amati drill point in the back, but often not just one but three, usually evenly spaced between the two blocks. As has been mentioned, the ribs are inset into channels around the back perimeter in the manner one sees in Vieux Paris School violins, although in Cattenar’s work the channels rarely if ever cut through the tips of the corners to become visible. Cattenar’s scrolls also follow the Amati tradition but with volutes somewhat smaller in proportion to the pegboxes than the Cremonese style. His wood selection is generally always local, with a distinctive fleck that one sees in woods from their mountain regions. A particularly fine example is the violin currently in the Chi Mei Collection in Taiwan (ID 59629), and several have in recent years surfaced in auctions in the US and UK.

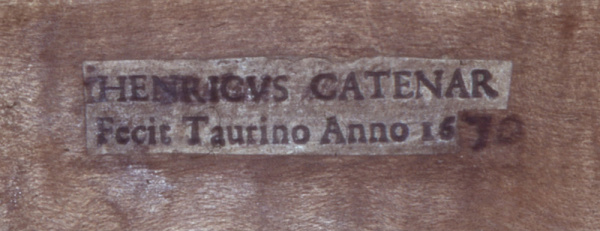

The label of a 1670 Cattenar violin. Photo: Philip J. Kass

In the Arisi manuscript (an essay by a priest named Desiderio Arisi about the famous Cremonese of his day, which includes the earliest biography of Antonio Stradivari) it is mentioned that Bartolomeo Grandi, concertmaster of the ducal ensembles, was sent to Cremona in the 1680s by the duke to acquire an ensemble of Stradivaris. There exist no documents in the ducal payments indicating that such a purchase was ever actually made. However, the surviving work of this period shows that the makers were now aware of Cremonese instruments and had adapted their construction methods to be more in keeping with that system, although they never gave up their inlaying system as they appear to have been unaware of the Cremonese interior-form technique.

In 1696 France invaded Piedmont at the opening of the War of Spanish Succession (1696–1713). Piedmont was overrun at various times during the war, and for survival’s sake switched sides several times, but by the end of the conflict came out on the winners’ side and was rewarded with the Kingdom of Sardinia. From this point all the old ducal organizations became royal ones, including the musical ensembles, henceforth called the Cappella Reale, soon to be joined by the royal opera, the Teatro Regio. These ensembles remained of vital importance to the progress of both music and instrument making in Turin.

A c. 1690 cello by Gioffredo Cappa, whose work stands apart from that of his Turinese contemporaries. Photos: Daniel Lane, Tarisio

More photosIt was during this period, at the end of the 17th century, that a maker made a brief appearance in Turin: Chiaffredo Cappa (1653–1717), from the semi-independent Marquisate of Saluzzo. Cappa is to me an independent figure unconnected to the instrument making community in Turin. His presence in Saluzzo can be traced throughout the years when he might have studied there, and in any event his manner of working is at odds with the methods of the Turinese. His instruments do not use the method of inset ribs, nor are the choice of woods or the rest of his construction akin to that of Turin. Nonetheless, he remains an interesting and distinctive presence in Piedmontese violin making.

The next violin maker to appear in Turin had strong connections to the royal court. Giovanni Francesco Celoniato (1676–1751) had a sister who was a lady-in-waiting to the royal princess, as well as four sons who occupied positions of importance in the Cappella Regia and Teatro Reale. At least two of his sons occasionally made instruments – his eldest son, Giovanni Giuseppe Celoniato, is known from a few violins of the 1720s, and his youngest son, Filippo Antonio Eugenio, known as Eugenio, made one surviving example of a curiosity of that century: an instrument known as the pochette d’amore (as expected, a combination of those two instruments).

A cello head showing the distinctive hand of Giovanni Francesco Celoniato. Photo: courtesy of the Royal Academy of Music

Celoniato’s instruments show a strong affinity to the work of Cattenar, who lived around the corner from him in the 1690s, but have a rather more rigid and less Amati-aware model. Some have described this model as Stradivari influenced, but other than the longer corners (actually quite delicate in design) and the straightness in the outline as it moves away from the C bouts, they have very little in common. Like Cattenar, his ‘f’s have stems that are almost straight, but with the holes sharply turning inward towards it. His scrolls are particularly distinctive, with long and very narrow pegboxes topped with fairly small volutes and an open throat, but with the final turn running all the way up to the top (like midnight on a clock face). He continued to follow the construction methods of the previous generation, including setting the ribs into a channel in the back, although with a much harder, firmer varnish, usually a gold to gold–orange in color, which makes the work of this period resemble those of the contemporary Paris school. His instruments range from the 1720s to the early 1740s, the last dated being a pochette d’amore of 1745.

The court continued to import French talent (the music master of the Chapel of the Holy Shroud was the nephew of the French composer Couperin), but the flow began to be more bi-directional. During these years one of the preeminent violinists and teachers in Italy was Giovanni Battista Somis, the director of music in the royal court. He had many students from France (one of whom was Jean Marie LeClair), and he and his colleagues increasingly traveled to Paris as performers. This was continued by his successor, Gaetano Pugnani. That flow also included many if not most of the instruments made by the earlier generations, for the French were avid buyers of Italian violins, which Turin was able to supply. The Piedmontese instruments were mostly relabeled, or were soon to be relabeled, as Amatis. This is a significant reason why so little of the early work is readily identifiable as Piedmontese, and why their makers drifted so quickly into obscurity.

Several individuals known to us as violin makers also made the journey to France. Andrea Castagneri (1696–1747), born in the same block as lived both Cattenar and Celoniato, traveled to Paris as a page in the service of the Duke of Carignan, a cousin of the king of Sardinia. Once there, he joined the French court ensemble known as the 24 Violons du Roi, and later became a violin maker and in particular a music publisher, a profession continued by his daughter after his death. He was joined by his nephew and successor Joseph Gaffino (c. 1720–86). Their work is fundamentally akin to the Paris school and has relatively little resemblance to that of the Celoniato instruments.

A c. 1770 cello by G.B. Genova; strong similarities with the work of Celoniato suggest that he was Celoniato’s pupil. Photos: Robert Bailey, Tarisio

More photosCeloniato suffered a major illness in 1746; he drew up his last will that year and no further work is known from his hand. At this stage a maker whose work bears a strong affinity to Celoniato’s appeared on the scene: Giovanni Battista Genova (active 1740s–1770). Genova’s work is so similar to Celoniato’s that we are probably justified in thinking of him as a pupil and successor to the latter. Unlike Celoniato, Genova had no direct connection to the court, but the Celoniato family so dominated the ensembles that this was probably not an issue. Few of Genova’s instruments today bear labels, many of which are dated 1770, the year of an authentic label reproduced in the early label books. It does, however, seem that he ceased active work at around that date.

Two other makers deserve attention from this period. Nicola Giorgis (d. 1747) was an inn keeper, from whom are known a few violins, rough works in the traditional manner. He may have been self-taught. Lastly, there is a strong affinity in construction, materials and varnish (though not in model) between Celoniato and Spirito Sorsana (active 1720s–30s). Sorsana worked in Cuneo, a frontier fortress town on the passes leading into Nice. While he worked near to Saluzzo, there is nothing in his work to suggest a teacher–pupil connection between him and Cappa.

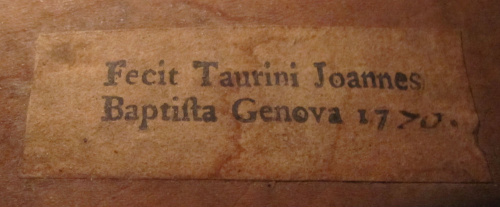

A rare original label by G.B. Genova. Photo: Tarisio

Philip J. Kass is a respected expert on classical violin making and has written extensively for the Journal of the Violin Society of America, The Strad magazine and other periodicals, as well as contributing many entries to the New Grove Dictionary of Music. In part 2 of his survey of Turinese violin making he investigates what happened after G.B. Guadagnini’s arrival in the city in 1771.