A cello made by Peter Petersen Adamsen in 1891. Photos: Tarisio

The turn of the 20th century brought new changes in Danish society. By 1900 around 25,000 people in Denmark had telephones installed [1] and gramophone records began to spread. From 1925 Danish National Radio broadcasted news on a regular basis and later its ‘Thursday night concerts’ with the newly established Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra made classical music available to listeners across the country. The crises of the World War 1, the Wall Street financial crash in 1929 and World War 2 had a noticeable impact on everyone. But as we have seen previously, art and craftmanship has a tendency to survive.

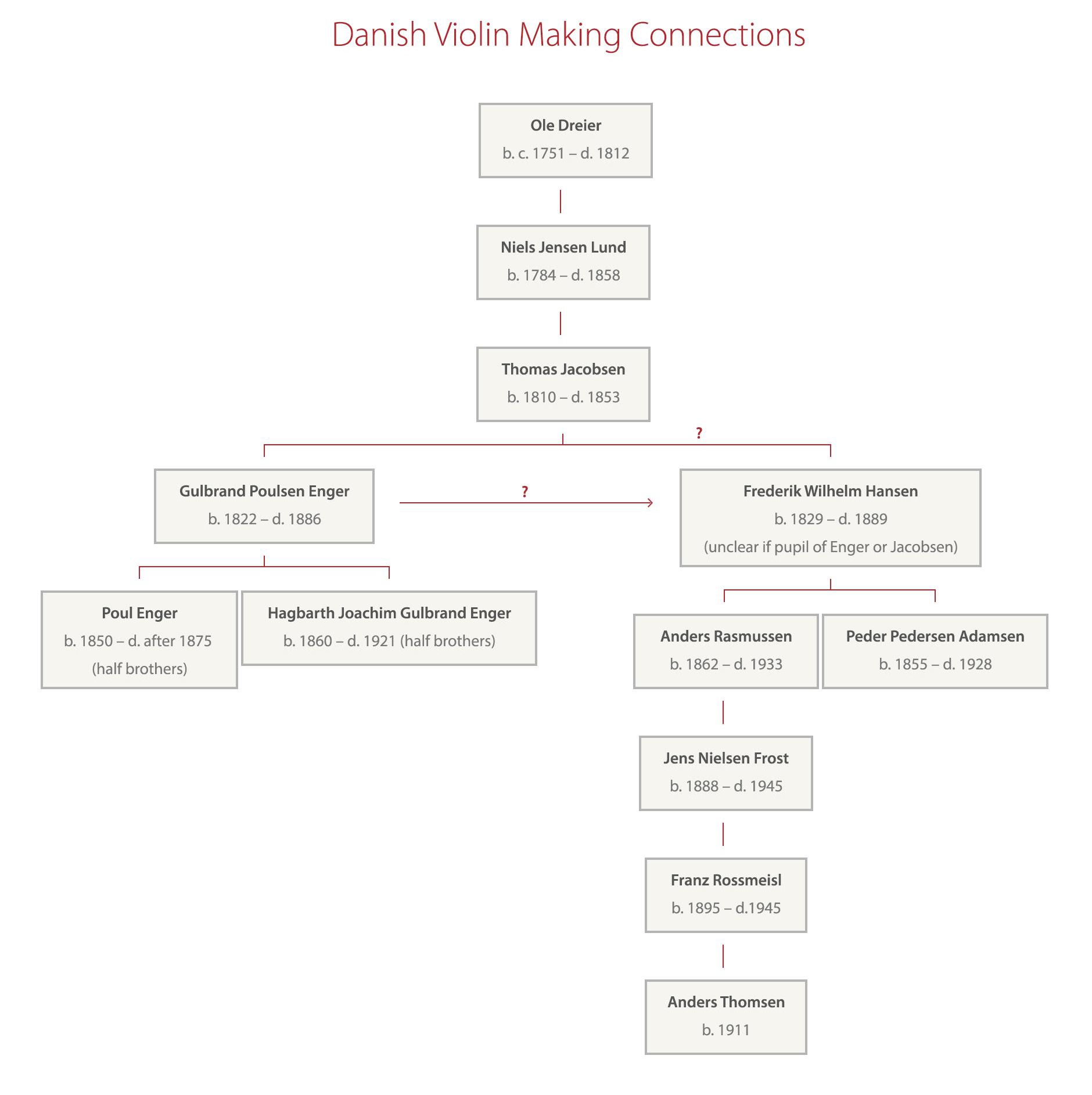

Among violin makers active at the turn of the 20th century we find Peter Petersen Adamsen (1855–1928), one of Denmark’s most prolific makers. He was born in Fyrkilde, North Jutland, and trained with Frederik Wilhelm Hansen in Randers, Jutland, during 1874–76. Together they reportedly produced around 15 instruments a year.

Adamsen later traveled throughout Europe and in Italy he met his wife, Lodomilla Giovanne Maria Biza, who was of Austrian–Hungarian descent. In my research I have found Adamsen at 38 different addresses during his lifetime, suggesting that his income was unpredictable. His official surname was Petersen (the name Adamsen is found in previous generations of his family, and Adamsen, like many of his siblings, used both names) and in January 1906 he applied to the Danish king to be allowed to use the name Adamsen as his surname instead, which would place him alphabetically near the top of the musical instrument makers’ section of the Copenhagen telephone directory. [2]

His early instruments (c. 1876–1900) are very reminiscent of those of Hansen. From 1900 he was hospitalized for four years with stomach ulcers and after he returned to work in 1904 his instruments become somewhat heavier. From 1922 onwards he used elaborate labels made from parchment with letters printed in gold. This was also the year that his wife, who had been suffering from paralysis for more than 12 years, finally died.

Hans Poulsen (1861–1949) was another prolific maker; he studied in Germany with the Schuster company in Markneukirchen and A.R. Breinl in Grasslitz and in his applications for funds to finance this trip, he specifically wrote that he wanted to study violin manufacturing (as opposed to learning from makers who produced fewer instruments but of the highest quality). His instruments are very consistent in quality throughout his career and show a secure hand. His workshop was for most of his career in Lille Kongensgade, which at the time one might call the Rue de Rome of Copenhagen since several musical instrument makers worked there, and both of his sons worked for him. One of them, Hans Aldolph Martin Poulsen, later made violins that are difficult to distinguish from those of his father.

Anders Rasmussen (1862–1933) studied briefly with Frederik Wilhelm Hansen around 1888–89. During his military service in Aarhus he played the trumpet and was instrumental in creating Denmark’s first musicians’ union. His early instruments show some influence from Hansen; later instruments tend to be somewhat heavier in construction. In 1913 he emigrated to Omaha, Nebraska, to start a new career. Around 1918 he seems to have changed his mind and after a delay of around a year, when he was stuck in New York city due to the Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918–19, he returned home to Copenhagen.

Rasmussen invented and patented a mechanism to stop the 75rpm phonograph records once the needle had reached the end of the groove. This had an ironic aspect to it: Rasmussen sold both musical instruments and phonograph records, and during the 1920s phonograph records spread rapidly. This had a negative impact on the many musicians playing live music at restaurants and in other public places, which in turn made life difficult for some violin makers.

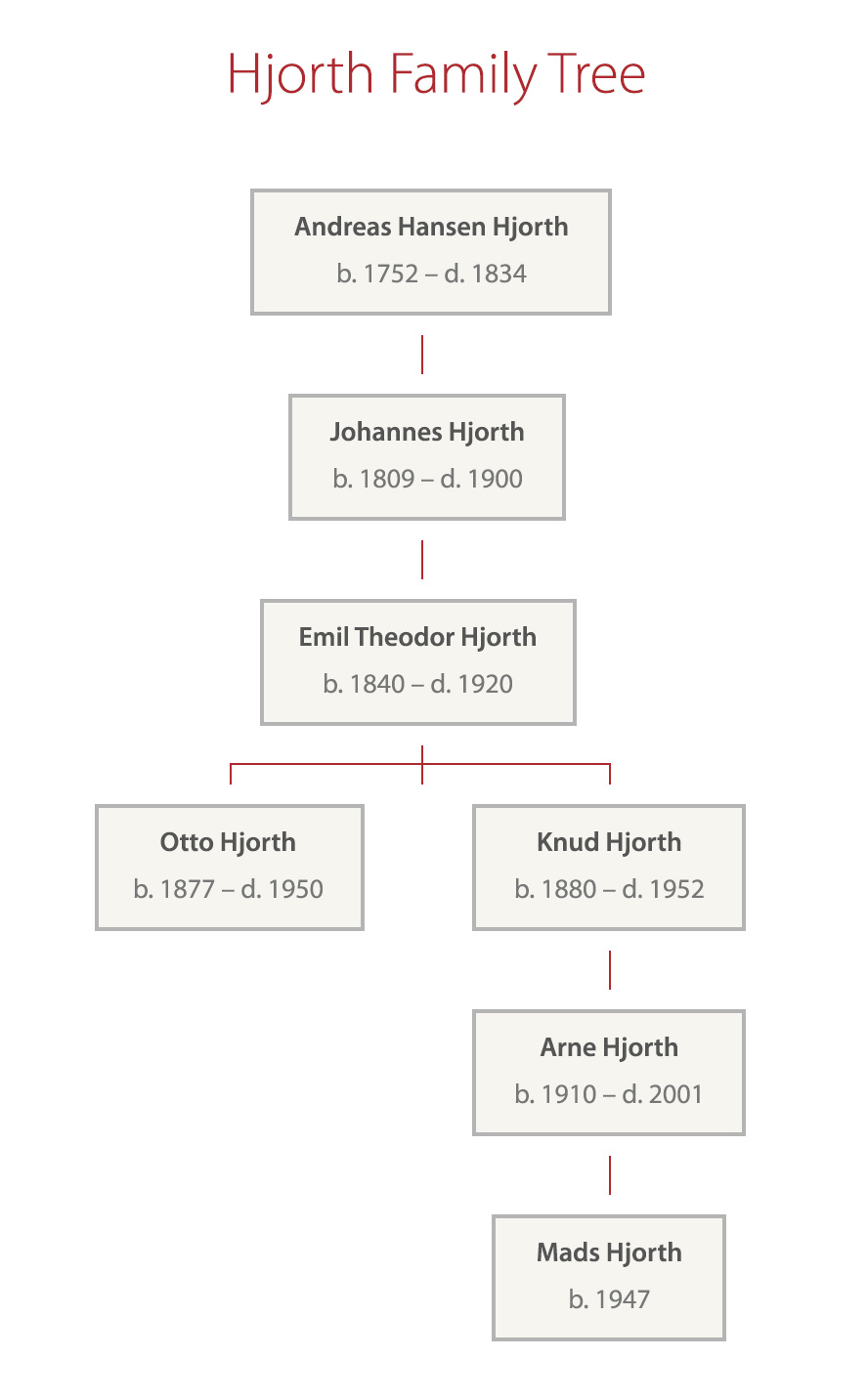

Meanwhile the Emil Hjorth & Sons firm was flourishing in Copenhagen. It was by now run by Otto and Knud Hjorth, sons of Emil Theodor and the fourth generation of the Hjorth dynasty.

Otto Hjorth (1877–1950) was trained by his father from 1892 and a violin made when he was 15 shows that he was talented from an early age. Following the Hjorth tradition, he studied in Paris with Georges Cunault 1900–02 and a French influence is evident in his instruments from this point. With Knud he expanded the Hjorth business and from 1908 they employed the French-born Georges Falisse (1885–1981), who was to remain with the firm for over 50 years (until 1961) working as a restorer and also making many instruments in the white.

Knud Hjorth (1880–1952) studied with his father from the age of 16. He went to work for Ernst Kessler in Berlin in 1904–05, where he learned more about international trade and had access to many fine instruments. It was Knud who excellently varnished the instruments that Falisse made in the workshop.

From approximately 1908 until 1930 the Hjorth firm produced quite a large number of Stradivari- and Guarneri-inspired models (for example no. 100 was made in 1913, no. 200 in 1921 and no. 300 in 1931), and these instruments were usually fully varnished ‘as new’. After 1930 until around 1950 the firm began to produce copies of the many great Italian instruments that passed through the workshop, such as Nicolò Gagliano, Pietro Guarneri of Mantua, Nicolò Amati, G.B. Guadagnini and so on – these are varnished ‘en imitation’, with the wear patterns and scratches of the originals meticulously copied, often with a very pleasing result.

The Hjorth brothers employed and trained many excellent luthiers and the shop continued making fine new instruments during World War 2, despite the constraints of the war.

The Hjorth brothers employed and trained many excellent luthiers and the shop continued making fine new instruments during World War 2, despite the constraints of the war.

Johan August Friderich Hoffmann (1867–1934) was German by birth and worked for Emil Theodor Hjorth from around 1893 till 1900. He married and became self employed in Copenhagen in 1900, mostly doing repairs and some new making. His early instruments are rather German in character with a thin spirit-like varnish, but after around 1920 he switches to a thick oil-based varnish with a tendency to crackle.

Hoffmann’s shop was in Skindergade no. 49 and, as in many other violin making cities, his colleagues (Hjorth, Merling, Bojesen-Petersen, Adamsen and so on) worked in close proximity, all within a square mile. This made life easy for customers, but life for the violin makers might at times have felt oppressive thanks to the close proximity of so many competitors.

Simon Christian Bojesen-Petersen (1882–1980) trained from 1898 till 1901 with Johan August Friderich Hoffmann in Copenhagen. He opened his shop in Vestergade no. 1 in 1901. Here he made and repaired instruments energetically until around 1940, when the Nazi occupation of Denmark probably made life difficult for him, as he (his family has told me) was a quarter Jewish. In the late 1930s he had formed a cabaret ensemble named the Buson Orchestra and created some highly curious instruments with flashing electric light bulbs, tribal feathers and animal heads for their use in variety-show performances.

Like Adamsen, at some point he changed his family name by adding a hyphen between Bojesen and Petersen – this way making sure that his name would be towards the top of the list of violin makers in the telephone directory. He was the first teacher of Pauli Merling and from 1933 onwards Merling ran his own rather larger shop next door at Vestergade no. 3 – this probably wasn’t ideal for Bojesen-Petersen, who employed only his son in the workshop.

Jens Nielsen Frost (1888–1945) is a somewhat flamboyant character among the Danish makers. He apprenticed with his father as a carpenter, then studied violin making with Anders Rasmussen in Aarhus, Jutland, until 1910, when he opened his first workshop. In 1917 he moved to Aalborg and worked until 1927, when he went bankrupt. He divorced, abandoning his ex-wife and a number of children, and moved to Copenhagen where he remarried and had four more children. It was here that he finally seems to have had success as a maker and repairer.

From this point until his death Frost had a close working relationship with the Pro Arte Quartet of Belgium, which apparently performed the Bela Bartók quartets on Frost instruments. [3] His workshop became a meeting point for many chamber musicians. His instruments are usually branded with his name, a serial number, the year and sometimes ‘Pro Arte’, indicating that it was an example of which the Pro Arte Quartet had approved.

During childhood Frost had suffered from tuberculosis and in October 1945, after a late-night ride on a horse-drawn carriage, he caught pneumonia. Penicillin had just arrived in Copenhagen, but Frost refused to take this ‘modern stuff’ and died soon afterwards.

A 1939 violin by Pauli Merling, who established his own firm in 1919. Photo: Ingles & Hayday

Pauli Merling (1894–1976) is a well-known name in the history of violin making in Denmark. He studied with Bojesen-Petersen from 1909 until 1913 and then moved to Germany to study with Rudolf Heckel in Dresden. From 1914 till 1915 he worked in Oslo, Norway, with Rummelhof Hansen and lastly he worked with Emil Hjorth & Sons in Copenhagen from 1915 until 1919, after which time he became self-employed and established a successful workshop.

Merling instruments show the influence of his masters and one can detect both German and French inspiration. From 1927 the German violin maker Karl Heinel made most of his instruments in the white, which Merling then varnished. Besides making new instruments the shop dealt in fine old instruments and bows on an international basis. At its height the workshop employed four or five craftsmen.

Merling’s daughter, Cony Ida Merling (1927–2001), learned with him from around 1950–53. She studied for a while with Henry Werro in Berne, Switzerland, and took over the Merling business in 1976, when her father tragically committed suicide shortly after his wife’s death. Cony then ran the business, being one of the very few female maker–dealers in the world, and brought it to a more international level. In turn her son, Henrik Merling, took over around 1980 but sadly he died of cancer aged just 33 in 1987, ending a family business that had lasted nearly 70 years and employed several excellent craftsmen.

One of these employees was Karl Heinel (1907–1993), born in Markneukirchen, Germany, into a well-known family of violin makers. He came to Copenhagen in 1927 to work for Pauli Merling until the occupation of Denmark by Nazi Germany in 1940. As a German citizen, he was forced to enroll for German military service on the eastern front in Russia and from 1945–48 he was incarcerated in a Russian prison camp. Upon his return to Denmark he resumed working for Merling; in all he made a vast number of the Merling instruments until 1951, when he opened his own workshop.

Arne Hjorth (1910–2001) represents the fifth generation of the Emil Hjorth & Sons firm. He received his first training from 1926 with his father Knud and uncle Otto. In 1934–35 he studied with Charles Enel in Paris and later in 1935 with Schuster in Graz, Austria. After the deaths of Otto and Knud in the 1950s he took over the business.

Arne made some instruments following the Hjorth tradition in the French style. He also made some on a more ‘Italianized’ freestyle outline and construction. These he labeled: ‘Cervus Capriolus Aquila Fecit’ and here a bit of Latin translation is necessary. The name Hjorth means ‘deer’ in Danish. In Latin, ‘cervus capriolus’ means a small deer – refering to the fact that Arne Hjorth was the junior or youngest in the firm. The name Arne is old Nordic for ‘Ørn’, which means ‘eagle’ and in turn is ‘aquila’ in Latin.

In 1950 Arne was a founding member of the International Society of Violin and Bow Makers (the Entente) and in 1963 he wrote the book Danish Violins and Their Makers. Today his son, Mads Hjorth (b. 1947), represents the sixth generation of the family’s violin makers and runs what is now the world’s oldest violin business, which has operated in an unbroken line from father to son for 227 years!

This ends our journey through the history of Danish violin making. The country’s makers experienced various economic and political ups and downs during their careers. But it is worth remembering that stringed instruments, like architecture and works of art, are part of the heirlooms that any generation leaves behind. Kept in good preservation, they help us to understand the history of which we are all part.

Maker and expert Jens Stenz has extensively researched the history of violin making in Denmark and owns a large collection of Danish instruments. In part 1 he discusses the country’s earliest stringed instruments, while part 2 covers the golden age of Danish violin making.

Photos courtesy of Jens Stenz unless otherwise marked.

Notes

[1] According to records at the Technical Museum north of Copenhagen.

[2] The official letter/application was signed by Adamsen and his wife on January 3, 1906; we have no copy of the reply, but the request appears to have been granted.

[3] An old newspaper cutting from c. 1940 shows the Pro Arte Quartet playing at a public concert on white J.N. Frost instruments because he didn’t have the time to finish them before the quartet arrived in Copenhagen.