In the 1980s Thomas Wenberg made it his mission to track down and interview over 3,500 violin makers across America. The result was a seminal book, ‘The Violin Makers of the United States’, and the deluxe limited edition of 100 volumes sold out immediately. This November the very first volume of the deluxe edition will be sold in Tarisio’s New York auction. Here, Wenberg (who later changed his name to Wilde and became an Oregon state senator) looks back on the project that obsessed him for three years.

I had a great many learning disabilities as a child – severe dyslexia and ADHD, although we didn’t have those terms then – and I had accepted the fact I would spend my life being somewhat illiterate. But as many people do who have a weakness in a particular area, I became obsessed with violin books and collecting them – that which you are least able to do is what you most desire. For 15 years this was all I did.

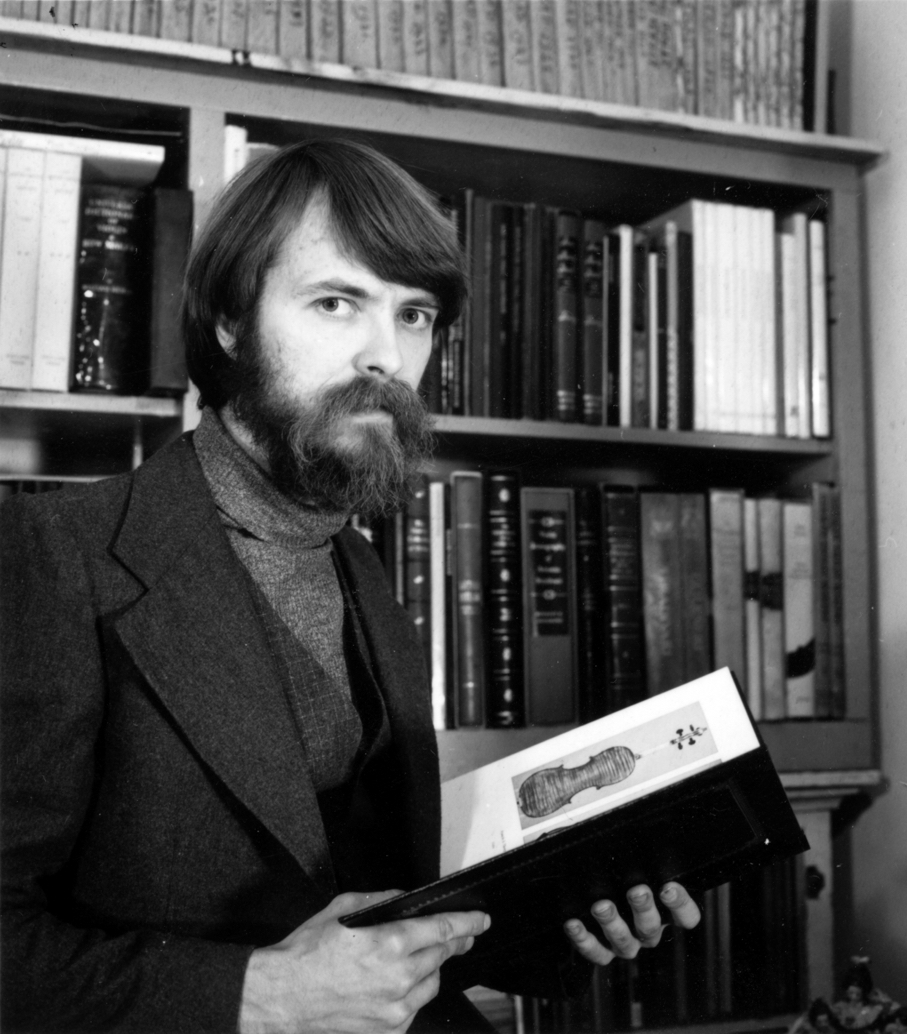

Thomas Wenberg in 1986 with a copy of the newly published book. Photo © 1998 Strings magazine

My father was a vice-president of the University of Minnesota and a learned scholar in many areas of world history, but primarily World War II, during which he led his men on to Omaha Beach on D-Day. Many people had asked him to record his knowledge so that it could be passed on to others, but he died suddenly at the age of 62 and, like a blast of cold water to the face, I realized that vast knowledge was gone forever. And while it’s true that I wrote the book on American makers because there was a hole in my collection that I needed to have filled, the truth is I was so angry with my father for never publishing his knowledge and having it all die with him that I was determined to make up for it.

I had another very personal reason for writing the book. My learning problems had turned me into a pretty extreme introvert and my group of friends easily could be counted on one hand. Just saying hello to another person caused a great deal of anxiety. Things such as public speaking or making contact with someone I did not know brought me close to having a heart attack. So being a very self-directed person, I decided the best way to deal with it was to write a book. And not just any book. An encyclopedia. One that involved talking to hundreds and hundreds of people, most of whom I had never met.

Just saying hello to another person caused a great deal of anxiety. Things such as public speaking brought me close to having a heart attack

I set out in 1983 in my new Mazda pickup with a fiberglass shell on the back and foolishly thought I could just lie back there at night and sleep. I didn’t mind the police knocking on my window to check on me, because invariably we would sit around and talk violins and then I’d go back to sleep. But in Houston one night I parked by an apartment complex figuring no one would bother me. Wrong! I hadn’t fallen asleep yet, when a car pulled up right behind the truck, a guy jumped out and leaned with his back against the side of the truck about two feet from where I was lying and started shooting a gun between two of the apartment buildings. He didn’t turn around, but got back in the car and they sped away. No police ever arrived and no one came past the truck again that night. But after several interviews in the area I drove back to Oregon and made a curtain system that went entirely around the inside of the shell so that I could sleep with a bit of privacy.

On another occasion after I arrived in New York City, I parked by my friend’s apartment in Brooklyn and started taking my things into the building. When I returned to the truck I found the rider’s side window shot out so I called the police – that was one of four police reports I filed while in the New York City area. The next day I got the window replaced and went uptown to see the violin restorer and maker Luiz Bellini. We had a long and enjoyable discussion that lasted well into the evening. By the time I headed back to Brooklyn the sun had set. I went to turn on the headlights and found I did not have any. I had failed to notice the previous day that both headlights had been shot out as well. On top of that my map had been left at my friend’s apartment. So I drove the entire 30-minute drive without lights and without directions in an unfamiliar city. It was one of the many times my sense of direction served me well.

One maker I interviewed was a hobbyist who was an avionics engineer and had come up with the design for the original swept-wing aircraft. In the middle of the interview he suddenly stopped and said he was having so much trouble with his teenage son was there anything I could do or suggest, since I seemed off-beat myself. I tried giving advice, but I am pretty sure I was no match for Dear Abby.

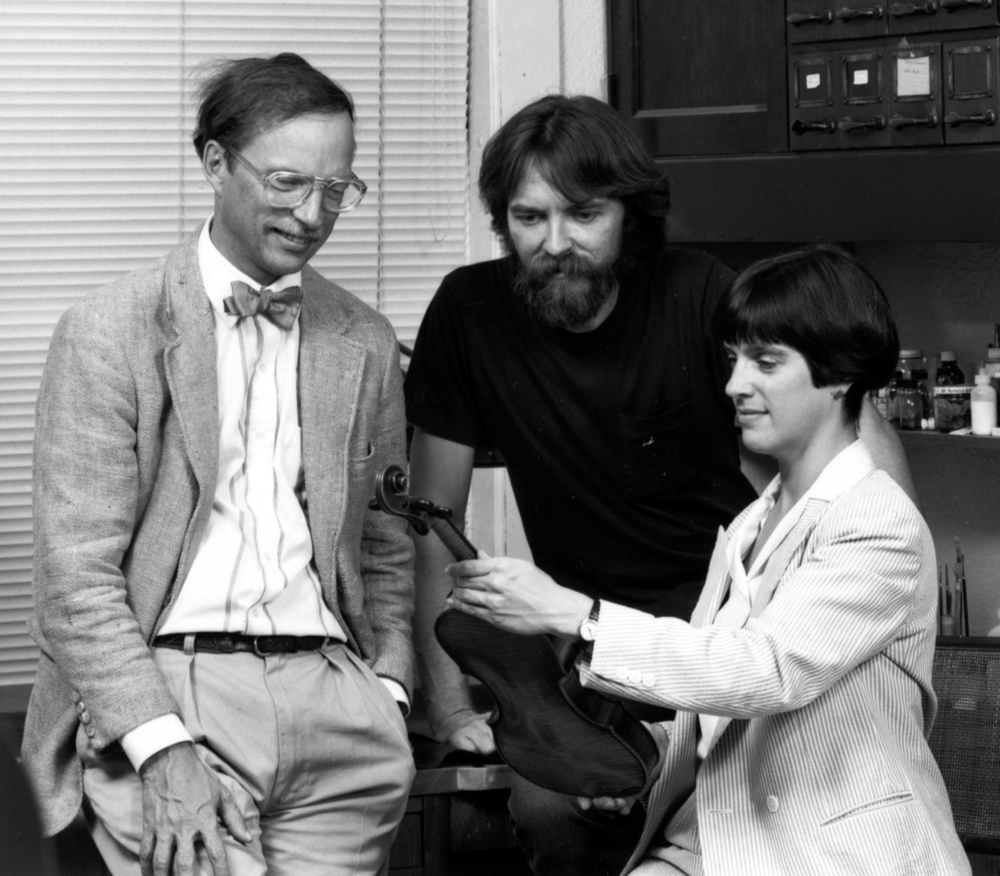

Wenberg (center) with Bruce Carlson of the Schubert Club in Minneapolis and violin dealer Claire Givens in 1988. They worked together on a separate publication, ‘The Violin and Bow Makers of Minnesota’. Photo © 1998 Strings magazine

Another hobbyist maker, who was a design engineer for General Motors from the early days, when they did their modeling in clay, had received many awards for his work. This interview was notable to me because it was one of the few times anyone asked me to stay to dinner. It also stands out because I was in the area of the Great Smoky Mountains and this was where I drove to relieve the stress and my dislike of large cities. I actually wore out two cassette tapes of Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring during this time. Nothing was better than to park on a hilltop with that music playing and watch the sun slowly set behind the hills.

I would try to be by myself and watch every evening’s sunset. I could feel myself relax and I would mentally rerun the interviews of the day making certain I did not miss anything prior to moving on. As an introvert who found it completely foreign to barge in on people’s lives only to leave just as quickly, I desperately needed that quiet time to collect my thoughts and get ready for the next day.

In Texas I heard there was a violin dealer and repairman in San Antonio, so I tracked him down. He had quite an operation set up where appraisals were on a percentage basis and many of the instruments were then donated to a major university for the appraised value. Just about any instrument brought to him was apparently an old Italian and everyone came out a winner. He made big bucks doing the appraisal; the person donating the instrument received a large tax break; and the university got instruments for student use. He took me to an underground vault he had built in the back yard where he kept his most valuable instruments. He handed me violins one by one and wanted me to identify the maker. Every one of them had been revarnished using his secret formula and I was at a loss for words as I examined them. I don’t think a single one was even of Italian origin, but it was very hard to tell.

As I made my way into Philadelphia I stopped at a shop of a person who had worked for the Moennig shop. We got to talking about my next meeting, which was with William Moennig. I knew the shop had a long history and would be a wealth of information, especially with Philip Kass there. But I was warned that when Bill Moennig first met people in his office he would let his small glasses slide down his nose a bit and he would stare at the person, often for an extended period of time. I thought this was just a joke. But when I arrived at the Moennig shop, after greeting me warmly, Bill Moennig took me into his office and almost on cue he let his glasses slide down a bit and sat there staring at me. I really wanted to burst out laughing, but I had been told that if I could outstare him I would be treated quite well. I’ve never been one to stare at someone’s face for any length of time, but if it meant getting access to more information I was ready to do it all day if necessary. I think we came pretty close to five minutes, at which point he got up and said anything I might need was available and to feel free to ask anyone questions. I believe I sat in there taking notes for about three days.

I’ve never been one to stare at someone’s face for any length of time, but if it meant getting access to more information I was ready to do it all day if necessary

There were very few negative interviews, but I was at the shop of one maker who was highly regarded locally. His work was actually of student quality, yet every question I asked came back with the answer that it was a secret. He said he had done enough research to be able to reproduce the playing characteristics of a Strad and he knew the varnish recipe, which, of course, was a secret. In interviews I tried to be as tolerant as possible since I was dealing with artists who were often eccentrics. But I simply could not take it any longer and I pretty much told him he was talking rubbish. He pointed at the door and said, ‘You had better beat me to that door or you are going to regret it.’ This turned out to be a very useful line that I later used on a lobbyist when I was a senator!

Wenberg as an Oregon state senator in the 1990s; by this point he had changed his name to Wilde. Photo © 1998 Strings magazine

In a city with quite a number of makers there was one who refused to be in any book that included amateurs. I was going to include him, but I wanted to base his entry on his words and not hearsay. I made no headway in getting an interview the first time I was in the area. Months later I returned to find other makers I had missed, but he still gave me a flat refusal. The third time round it was getting closer to the deadline I had set for wrapping things up in order to get the book published on time. Still a flat refusal. Now I am easy-going to a point, but I have a very assertive side as well. At that point I told the maker, ‘You have a choice – you can give me what I need or I will print exactly what I have on you. I have given you three opportunities to comment, and no court will back you for refusing to correct any inaccuracies prior to publication.’ I received an immediate invitation to stop by. When I did, he immediately started going through my notes checking what I had on him, but also wanting to change information on other makers in the area, which I did not allow to happen.

In the end, if you were to map my route you would get dizzy. Unlike today where you just Google whatever you need, I’d stop in bars and talk to barbers and try to track down leads about as vague as, ‘Ya, I think Joe knows some fiddle maker out there a ways.’

I’d stop in bars and try to track down leads about as vague as, ‘Ya, I think Joe knows some fiddle maker out there a ways…’

The production of the book was enormous. I’d had no income for more than two years (my personal expenses were not great – almost never more than $5 a day and I would do things like wash my clothes with me in the shower) and the publishing expenses were substantial. For the binding of the deluxe edition I visited a tannery in Napa Valley and chose the glazed sheepskin, due to its incredible softness and rich look, but the week before I picked them up a Bible publisher purchased every glazed sheepskin hide they had and I was left wondering what to do. The tannery had just received a load of Moroccan goatskin and these were more expensive, but they gave them to me at the same price as the sheepskin. So the deluxe edition was bound in goatskin and I tried to include a small notice about this with each copy.

I had set a self-imposed production and shipping date of October 1, 1986 and I wanted to have the book finished before the VSA convention that fall. The first books were shipped on October 9 and I had all purchased copies shipped by the 15th – a bit short of my goal, but pretty decent.

Overall it was a very stressful time – I think it really took someone who was a bit peculiar to stick with it and see it through to completion. I doubt anyone would be crazy enough to try repeating what I did. I’ve never needed much more than five hours of sleep a night and writing that book required just about every waking hour I could devote to it.

The deluxe edition no.1 of The Violin Makers of the United States is Lot 1 in the November New York auction.