‘I don’t think Strads are easy to play,’ says Mullova. Photo: Foto Puck

Leaving behind a 1720 Strad you’ve played for three years would be difficult in most circumstances, but for Viktoria Mullova, letting go of the instrument when she defected from Russia in 1983 was the least of her worries: ‘I was so excited to escape, it was not my priority – I would have given up anything. I gave up my family. I could never imagine the Berlin Wall would come down and I would see them again, so at that moment I thought I wouldn’t. People always make such a thing that I left behind a Strad, but it wasn’t mine, and why should I steal it?’ Mullova made her break for freedom while on tour in Finland, leaving the violin on the hotel bed. It belonged in the Russian State Collection and had been lent to her for the 1980 Jean Sibelius Competition, which she won.

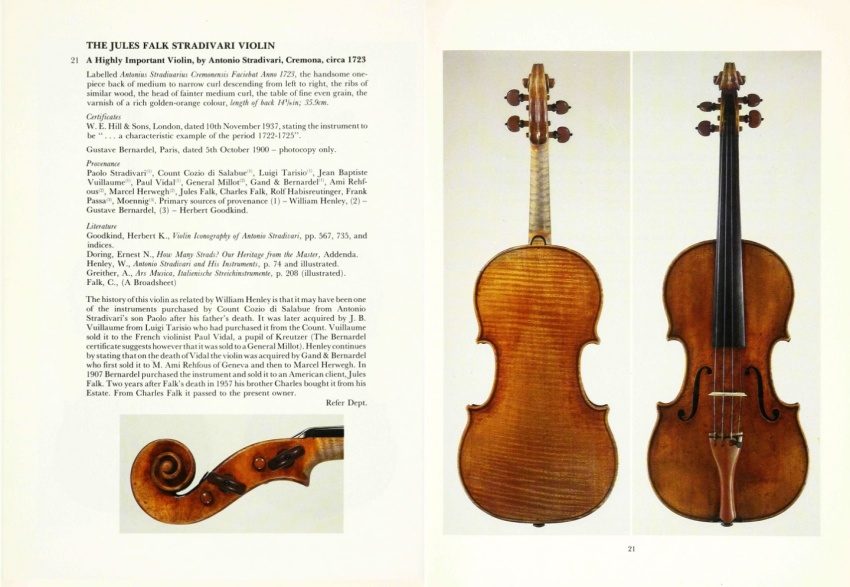

Today she plays the 1723 ‘Jules Falk’ Stradivari, which was bought for her by a foundation, and which she now owns. ‘I didn’t choose it: the foundation bought it for me at auction, but I was very lucky – it’s one of the good ones.’ This is not always the case: ‘Strads are all very different. There are some that are not that good or are uncomfortable to play. Some he made early on or are in bad condition. I’ve seen some that I was not impressed with.’

She describes the qualities of the ‘Jules Falk’: ‘It’s harmonious from string to string. Sometimes you take an instrument and the E string is easy to impress with, loud and bright, and then the D is difficult to get anything from and the G is strong again. My Strad is very balanced.’ Learning to play it offered challenges, though: ‘I don’t think Strads are easy to play. Every single note requires a different approach. If you play four notes on four different strings you have to put a little different pressure on each one – even from note to note. Now it’s automatic so I don’t think about it, but at the beginning it was hard. You have to know the instrument very intimately. It’s like a person. You have to know the intimate details of how to live with someone and it’s the same with your instrument – how it projects, what sounds you can make. If I were to describe Strads it would be as a little capricious and difficult to make respond. The good ones can have a very particular, beautiful sound and colour, but when you’re in a big hall I don’t think you can tell the difference. I wouldn’t be able to tell the difference. It’s the sound we make which is more important.’

The ‘Jules Falk’ was bought for Mullova from Sotheby’s in April 1985

Mullova firmly believes that a player’s sound rests with them and not their instrument: ‘If you can make a good sound you can make a good sound on any instrument, whether modern or French. Once, a few years ago, when we weren’t allowed to travel with instruments as hand luggage, I borrowed an instrument from an orchestral player and it still had my sound.’ She credits her father for helping her discover this: ‘When I was a small child my father spent hours teaching me how to make a sound, so I was very lucky to know how to do that from an early age. After that it’s up to you to develop different kinds of sound in the repertoire. I had my basic sound when I was small. It doesn’t relate to the violin itself. Some of my recordings I made on the Strad and some on the Guadagnini, and it’s still my sound.’

The G.B. Guadagnini is a 1750 instrument she has now set up for playing Baroque music, using a Baroque bow. Initially she played all her repertoire on the Strad, though: ‘One day I was recording Beethoven and Mendelssohn on gut strings and the next day I had to switch for Brahms. It was difficult for me to change from one to the other and to get used to the strings. I decided to look for another violin and found the Guadagnini, which I use with gut strings, so I can play a programme with both solo Bach and contemporary pieces.’

Swapping between the two violins still requires adjustment, though: ‘I use different pressure on the strings and on the bow, and a different bow speed. It’s a completely different technique so I have to be very quick to adjust in 30 seconds. When I started to play on gut strings it took me a few days to get used to it, but it became more and more easy. The pitch is half a tone lower, so Bach is easier than to play because he wrote for gut strings at that pitch.’

How do the instruments differ? ‘The Guadagnini is slightly smaller – the Strad is a bit bigger than standard. The Guadagnini has a very big sound – people don’t realise I’m playing on gut strings.’ And like her Strad, the sound is even across the strings: ‘The quality of all four strings is great – there’s no dip in the A or D, which are sometimes a problem, or in the lower strings, where you sometimes lose the power or beauty.’

Ariane Todes was formerly editor of The Strad magazine and is now a freelance writer and editor.