The Voller brothers, William, Charles and Alfred, became infamous in the violin world after being implicated as the makers of the fake ‘Balfour Stradivari’ at the turn of the 20th-century. It was one of the great scandals to rock the London trade and the Vollers became known as England’s greatest violin forgers.

Undoubtedly much of their activity formed a kind of sport. They produced copies of second-tier Italian works and floated them on to the market in order to outwit the experts, protected in part by the murky ethics of turn-of-the-century violin dealing. Their work includes some remarkable copies of Milanese and Neapolitan work, as well as less known makers such as Antonio Gragnani or Carlo Guadagnini. However, many of their instruments were correctly labeled and sold through reputable dealers, and often their finest efforts were reserved for making precise copies of famous instruments. Both John Hart in London and Rudolph Wurlitzer in New York openly engaged the Vollers.

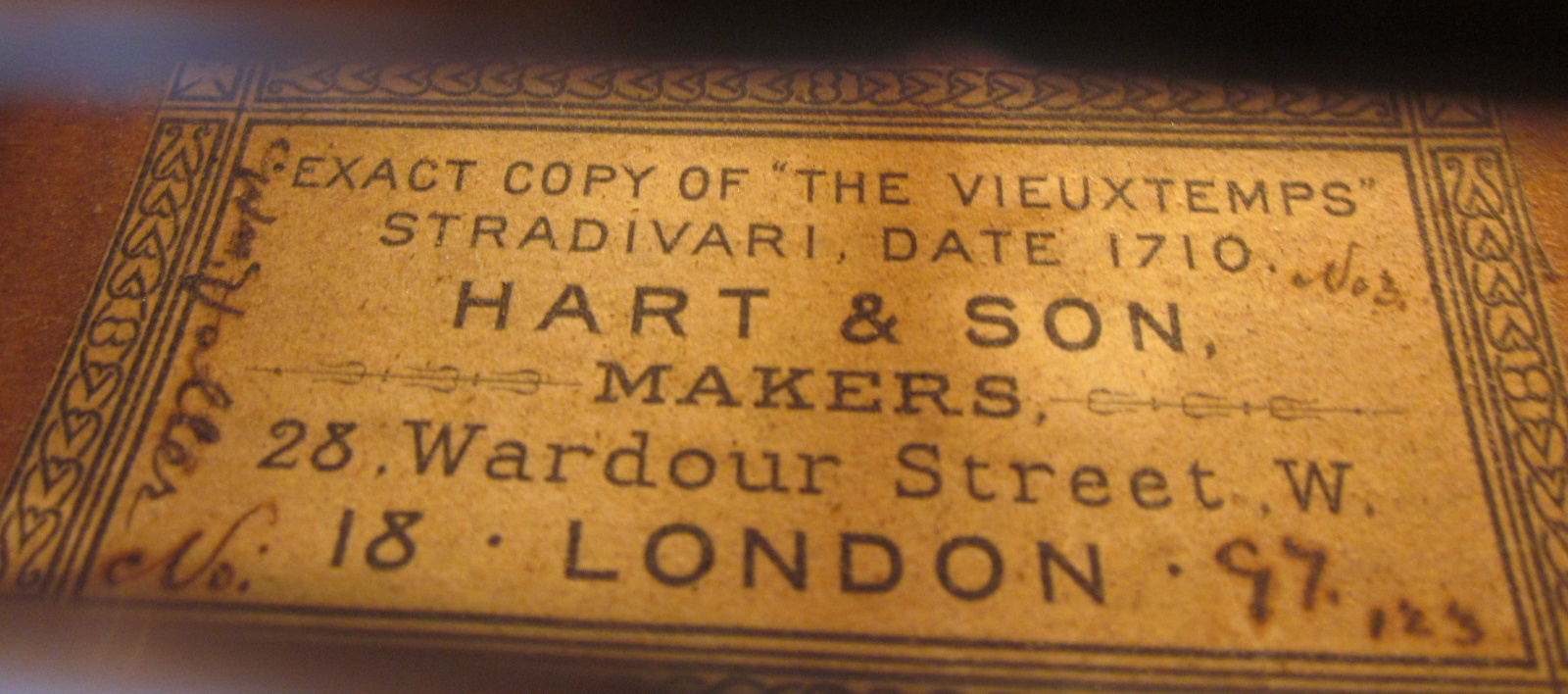

The ‘Vieuxtemps’ Stradivari copy, 1897

The Voller copy of the ‘Vieuxtemps’ Stradivari shown below is a fine example of their copying skills. The violin was made for Hart & Son, as indicated by its label, ‘Exact copy of “The Vieuxtemps” Stradivari, Date 1710. Hart & Son. Makers. 28 Wardour Street. W. 18 London.’ Made in 1897, it is one of several copies that Hart commissioned in the 1890s as a testimony to great instruments that had passed through his hands. These included the 1745 ‘Leduc’ and 1735 ‘d’Egville’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ violins, and the 1704 ‘Betts’ Stradivari as well as the ‘Vieuxtemps’.

A side-by-side comparison of the 1897 Voller copy with the original Vieuxtemps Stradivari (left) as it appeared in Fridolin Hamma’s Alt Geige in 1898

The claim to be an exact copy is hardly exaggeration. The choice of wood for the back of the violin is phenomenally close to the original and captures the subtle change of figure across the lower bouts. On the belly the sudden widening of the grain towards the edges is cleverly emulated by adding wings of broad-grained wood in the lower flanks. A curved scratch just left of the fingerboard is faithfully reproduced, as are large blemishes beside the purfling at the widest part of the lower bout and above the top treble corner.

The Vollers appear to have been vigilant against being discovered as forgers and particularly nervous when making copies of famous instruments. This presumably prompted their letter concerning the ‘Balfour Strad’, days before Balfour & Co put the violin on the market for £1,000 (they later doubled the price):

‘I should strongly advise you not to sell the so-called 1692 Strad, which you bought in at Putticks, as a Genuine Strad. You know it is only a clever “Fake”. If you do [sell it] I should think you could be prosecuted for conspiracy,’ signed famously, ‘One who knows who made it.’

Perhaps to protect themselves from the threat of litigation, the Vollers frequently incorporated obvious mistakes into their work. Their Gagliano copies often have pins in them, when an original should not, and similar ‘errors’ are seen on this Voller copy of the ‘Vieuxtemps’ Stradivari. Here, the lower back pin is directly under the purfling, emerging on both sides, while the upper pin sits below the purfling. This inconsistency is fundamentally un-Stradivarian and contrasts with the two pins neatly bisected by the purfling on the original.

The scroll, though a masterly copy in some respects, including superb reproduction of the wear to the back of the volute, lacks the black edges that are essential for a genuine scroll of this period. The deeply cut center line along the back of the pegbox is neither a feature of Stradivari’s work, nor is it typical of the Vollers’ technique. Again, this was possibly a warning to any expert to look again at the violin, or a safeguard if accused of conspiracy in a court of law.

Today Voller instruments are prized in their own right – not just as clever copies but as fine concert instruments worthy of the many professional musicians who play them.

Tarisio sold this Voller Brothers copy in 2013. Read John Dilworth’s feature about the work of the Voller Brothers.

Further reading

The Voller Brothers: Victorian Violin Makers, John Dilworth, Andrew Fairfax, John Milnes, BVMA, 2006.