As we saw in part 1, Bernard Ouchard steadfastly advocated the tradition of bow making that he learned from his father, Emile Auguste. Although he didn’t convey his techniques and philosophy in a lucidly articulated manner, his students nevertheless absorbed what some now refer to as the ‘Mirecourt way’.

There was no formal syllabus at l’Ecole d’Archeterie; the basic plan was variable but well conceived. The first couple of weeks were devoted to making the tools and the metal templates that would later provide precise measurements for the violin, viola and cello bows. (No bass bows were made there.) Then for one month the students would plane 30 sticks each. This was followed by learning how to bend the sticks properly, then making small corrections with the plane. Next came the head and mortices. Then the frogs – again, 30 of them. Sometimes Ouchard would alter the routine by assigning the students to different rooms – one for the stick, the other for the frog. After 15 months the students would finish their first bows. Some took even longer.

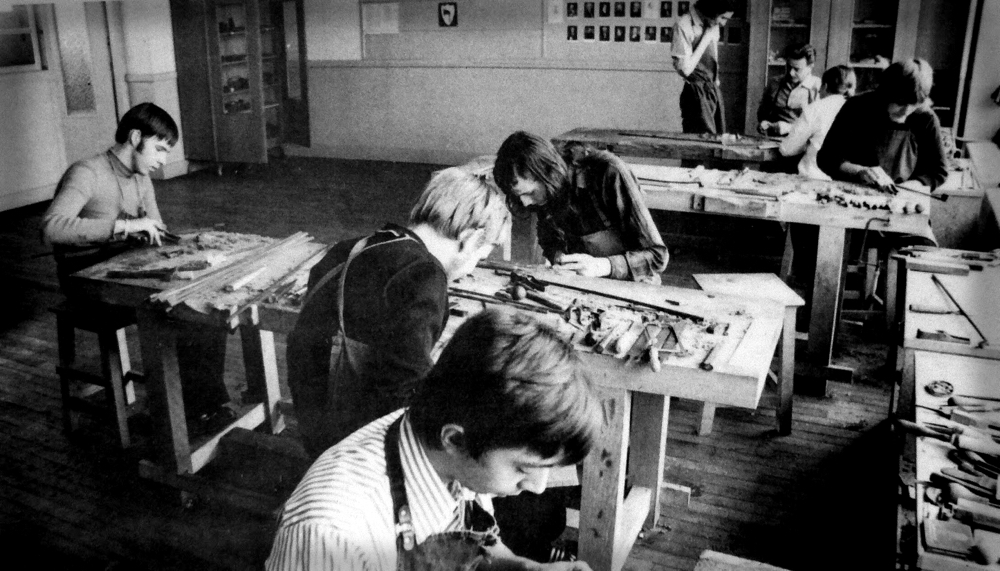

Mirecourt’s Ecole d’Archeterie in the academic year 1973–74. Clockwise from far back: Wilfred Hakoune (standing), Professor Bernard Ouchard, Sylvie Masson, Martin Devillers, Stephane Muller, Benoît Rolland, Jean-Yves Matter and Gilles Duhaut. Photo: courtesy Sandrine Raffin

One of the reasons why Ouchard’s approach worked well was because these students were unusually attentive and resourceful. Nothing they showed to Ouchard would escape the scrutiny of the others. Indeed, every step of the bow making process was influenced by the small triumphs and failures of those working at the nearby benches. The students would sometimes make tools for each other (Gilles Duhaut’s planes were especially popular). They would also share personal techniques that they’d developed – such as the one that Pascal Lauxerrois used to carve the head and beak. In all sorts of ways the students benefited from each other’s knowledge, skill and imagination.

Though Ouchard urged everyone to work rapidly, he didn’t allow shortcuts

Even though Ouchard encouraged creativity and initiative, he insisted on certain norms. Everyone’s templates had to be similar to his, and he also made it clear that a bow maker must take responsibility for every aspect of the sticks and frogs. (The buttons and ferrules were exceptions – Eric Grandchamp surmises that this may have been because the school didn’t have the appropriate lathe for these during the first years.) Though Ouchard urged everyone to work rapidly, he didn’t allow shortcuts. The notion of hiring others to make your frogs – or using unfinished, manufactured frogs – would have been unthinkable.

Since the school’s budget was limited, the materials that were provided were not always the finest. In the beginning, the only tools were those that had been donated by the Gillet family, and the wood came from Bazin’s attic. Later a local merchant named Gerome supplied wood that was of inconsistent quality. Somewhat better wood later came from Jean Schmitt in Lyon. When certain students felt they were ready for wood of the highest quality, they’d buy it themselves, usually from Bazin or Dupuys.

L’Ecole Nationale de Lutherie, Mirecourt, where Lionel Tasquier initially studied violin making

Only nickel-silver was provided, again because of the cost. On rare occasions when students wanted to use more expensive metals for their fittings, they would buy the silver or gold themselves. For lappings they used mostly nickel-silver wire. They also experimented with lizard, shark, fish skin, leather and tinsel/silk. Naturally there was heated animal glue, though white glue was also used for the grip and tip. Crazy glue (cyano-acrylit) was relatively new – and Ouchard detested it. They often used nitric acid to darken the sticks. Jean Grunberger recalls that they were later told about ammonia, though not by Ouchard. Their varnish consisted of gum-lac with a little oil.

The workshop’s scale was crude and inaccurate. ‘We used it only to weigh the letters that were to be taken to the post office’ – Gilles Duhaut

The weight of a bow is very important to most string players. According to the tradition that Ouchard taught, however, the scale should be used only after a bow is finished. In Mirecourt, it wasn’t used even then! Duhaut remembers that the workshop’s scale was crude and inaccurate. ‘We used it only to weigh the letters that were to be taken to the post office. Ouchard’s process was not so empirical. It was more by feel and experience.’ When I asked Jean-Pascal Nehr how he knows when the weight is right, he simply said, ‘The wood tells you.’

It may come as a surprise that Ouchard never urged the students to study bows by the great masters, and he would only rarely talk about how minute variations in the camber, the wood density and the balance can influence a bow’s playing characteristics. This only made those who were already curious about such things, including Benoît Rolland and Lauxerrois, even more curious.

All students were expected to demonstrate basic instrumental proficiency in order to graduate. Unless they were already accomplished players, they were required to take private lessons and perform a short piece in public as part of their final exam. This was no problem for those who could already play quite well – Christophe Schaeffer, Martin Devillers and Rolland, for example – but for others it was a challenge. Even though Ouchard didn’t play a string instrument himself, he accepted the school’s policy. According to Rolland, ‘He knew that playing was a real plus in this work because it tremendously helps to understand the functionality of a bow.’

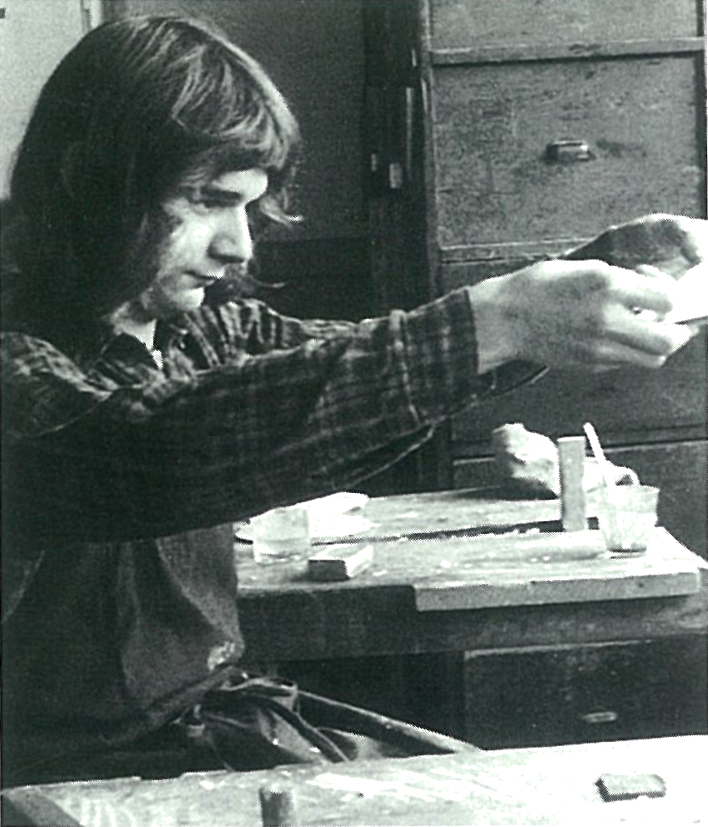

Lionel Tasquier (1957–1989)

Lionel Tasquier attended the violin making school in Mirecourt for three years but failed to graduate because it was believed that he had been disrespectful to one of the instructors. Disillusioned and despondent, he gave up violin making and worked for two years at a newspaper factory where he operated the printing presses. This was exhausting and dangerous work and he abandoned it after suffering a heart attack at age 25. Knowing that Tasquier was interested in bows, Rolland invited him to learn bow making, and before long Tasquier was working beside him in Paris. In just two years, he became ‘one of the most gifted bow makers I have ever seen.’

Lionel Tasquier. Photo: courtesy Loïc Le Canu

In 1982, when Rolland moved to the island of Bréhat, Tasquier followed him there and continued to work alongside him for another year. During that period Lauxerrois would often visit and the three of them would work alongside each other. With the support of Bernard Sabatier, Tasquier then opened his own small shop on rue de Budapest in Paris. But everything changed when he had a second heart attack, then a third and finally a by-pass operation. When he continued to decline, he was put on the waiting list for a heart transplant and after one year finally received a new heart. But his body rejected it and he died within a week at the age of 32.

Tasquier and Grunberger knew each other in Mirecourt when Tasquier was in his third year at the violin making school and Grunberger was in his first year at the bow making school. Grunberger describes him as ‘an unconventional guy with a true artist temperament.’ He was introspective and loved to paint and write poetry. He had a serious girlfriend, Fanny, but didn’t have many friends besides those who shared his passion for bow making or the guitar, such as Grunberger and Duhaut, who were both fine guitarists. They recall that Tasquier was an excellent player and composed a number of pieces – not simple chordal accompaniments to popular songs, but challenging and complex solo works. He didn’t write them down because he never learned how to read music.

In Tasquier’s bows, one appreciates the strong fundamentals of his training. They also reveal that he was not influenced by any particular style from the past. One reason was because he had not been exposed to many old bows, but it was also because he was tenaciously original. As Grunberger puts it, ‘Lionel went his own way, according to his feelings.’ This may explain certain unusual personal touches, such as the Japanese designs on the frog of one particular bow. But, not so unlike many of the masters, he was searching for a balance between an adherence to basic principles and his penchant for personal expression. He was still searching for that balance when he died.

It would be wrong to leave the impression that Lionel Tasquier and Pascal Lauxerrois were equals. Most of their contemporaries feel that Lauxerrois achieved a higher degree of sophistication, probably because of his obsession with old bows. But while Tasquier’s gift may not have matured as much by the time he died, his raw talent, creativity and technical skill were just as remarkable.

The beautiful bows made by Tasquier and Lauxerrois show us that anything is possible when gifted individuals, no matter their age or circumstances, summon the resolve and passion to give their absolute best. Their work also provides disquieting reminders that being a talented and dedicated 20- or 30-year-old is no guarantee that you’ll reach your maturity. They caution us that last week’s concert, the lesson we gave yesterday, or the instrument or bow that we finished only an hour ago could be our very last – perhaps the one by which people will remember us.

With thanks to the following: John Aniano, Sylvain Bigot, Alexander Caballero, Martin Devillers, Gilles Duhaut, Charles Espey, Olivier Fluchaire, Eric Grandchamp, Jean Grunberger, Séverine Lauxerrois, Susan Lipkins, Pierre Mastrangelo, Stéphane Muller, Jean-Pascal Nehr, Jean-Marc Panhaleux, Jean-François Raffin, Benoît Rolland, Marc Rosenstiel, Bernard Sabatier, Georges Tepho, Stéphane Thomachot and Matt Wehling.

Richard Young was the violist of the Vermeer Quartet from 1985–2007.

A longer version of this two-part feature is available to read on the Shar Blog.