Not a single bow by Pascal Lauxerrois or Lionel Tasquier has ever been sold by a major auction house. And most American dealers have never even heard of them. Of those who have, it’s unlikely that any have actually held one of their bows. Yet according to most of their peers, no one was more gifted than these two archetiers. Benoît Rolland states emphatically, ‘On their best days, Pascal and Lionel were better than any of us.’

These two makers have more in common than their obscurity and the outstanding quality of their work. Both attended l’Ecole Nationale de Lutherie in Mirecourt in the 1970s. Both died at a young age. And for each, the cause of death was related to heart issues. Tasquier was 32 when his body rejected a transplanted heart in 1989; Lauxerrois was 35 when he died of a heart attack in 1994 while working at his bench.

Ecole d’Archeterie de Mirecourt

In 1970 the bow making profession appeared to be nearly dead. As Stéphane Thomachot wrote, there were only three or four professional bow makers in the whole of France during the 1960s. [1] But in 1970 l’Ecole Nationale de Lutherie was opened in Mirecourt and one year later l’Ecole d’Archeterie was added, with Bernard Ouchard as the teacher. The inspiration for these schools came from Etienne Vatelot and Jean Bauer, whose motivation was both idealistic and practical. Besides wanting to re-invigorate the proud French traditions of violin and bow making, they wanted to ensure that there would be top-quality luthiers and archetiers to work in Europe’s many violin shops. This vision coincided with the desire of Marcel Landowski (the French Minister of Music) to re-establish Mirecourt as an important crossroads for French culture.

Aerial view of Mirecourt, where l’Ecole d’Archeterie opened in 1971

Today we can look back on the decade that followed as the dawn of a renaissance. But at the time who could have anticipated this? After all, the average age of those Mirecourt students was only 16 when they enrolled. Not surprisingly they displayed the usual strengths and vulnerabilities of teenagers. Moreover they were coming of age during the post-Woodstock era, when defiance and rebellion were as pervasive as idealism and reflection. Yet they succeeded. Today’s best evidence of this is the high quality of their bows, plus their enduring influence on younger bow makers.

For generations, the French education system has been rigorously selective. To this day, the grades that students earn largely determine whether they will continue with an academic education in college, or are recommended for trade schools where they learn skills that the government determines are beneficial to French society and culture. Students at these trade schools seldom come from well-to-do families, which may make them less likely to play a string instrument or to have a classical music background. L’Ecole Nationale de Lutherie and l’Ecole d’Archeterie were considered trade schools.

The students were selected through an audition process conducted by teachers from the two schools. Vatelot was also usually involved. Every year a small group (usually three) would be chosen for the bow making school from over 200 candidates. Each of these ‘classes’ would stay for three years, overlapping with other classes for continuity. The school was free, including the barracks-style dormitory, although many of the students moved to private accommodation after a year or two. These rooms were humble and unsupervised, and students cooked for themselves because most of them couldn’t afford restaurants. But life was good thanks to the camaraderie and independence that these living arrangements allowed. Like most teenagers, they could party with zeal and didn’t always get a lot of sleep. But almost all of them were committed to their work.

Bernard Ouchard. Photo courtesy Loïc Le Canu

At age 46, Bernard Ouchard, a member of one of France’s most important bow making families, had a prestigious position as the resident archetier with the Vidoudez shop in Geneva. But he grew frustrated having to devote so much of his time to repairing old bows rather than making his own. He also never got over his deep sadness when his father, Emile Auguste, decided to move to the US when Bernard was 21. In addition there were lingering emotional scars from his days fighting in the Indochina war. So when Vatelot pressured him to accept the position at l’Ecole d’Archeterie, he agreed, despite his Swiss wife’s reluctance to live in Mirecourt. It was in fact the city of his birth, where his family had lived for generations. And perhaps the prospect of teaching highly motivated young bow makers helped to assuage any disappointment that his own sons had decided not to continue the family tradition of bow making.

Not everyone could have handled the challenge of overseeing a workshop of teenagers. Perhaps it was Ouchard’s authenticity that enabled him to establish credibility and rapport with his students. They addressed him as ‘Maître’, but he didn’t put himself on a pedestal. He’d invite the students for lunch on Sundays and they would often meet him at La Vosgienne, a nearby bar. He even took the 15-year-old Éric Grandchamp to the local billiards hall to teach him carambola! He had friendly nicknames for many of them: ‘P’tit Jean’ (Jean Grunberger), ‘Blâmont’ (Gilles Duhaut), ‘Toulouse’ (Stéphane Muller), and ‘Chatou’ or ‘l’Artiste’ (Jean-Pascal Nehr). However, he was strict and his brusque comments could make some of them cry.

Gold-mounted violin bow by Bernard Ouchard for the Vidoudez shop in Geneva

While the students respected Ouchard, they were aware of his flaws – such as his unequal treatment of Sylvie Masson because she was a girl. It was also no secret that he drank too much, which may have contributed to his death in 1979. But looking back they are grateful not just for his knowledge and steadying influence, but for the confidence he helped them find. For many of them, he was much more than a teacher. Today, nearly four decades after his death, Nehr says, ‘it’s as if I still have to prove myself to him.’

Ouchard allowed the students to be independent and creative so long as they didn’t stray from the techniques and style he had learned from his father. His words were blunt and basic. According to Duhaut, ‘When we showed him something, it was either good or it wasn’t. He rarely explained WHY things should be done in a certain way.’ As a result, they did what students of most ‘old school’ teachers have done – they helped each other by reading between the lines and filling in the detail that Ouchard often didn’t provide. Though almost all of them were supportive, there was competition too, but this only accelerated their progress. There was also an unspoken hierarchy, with the older students usually taking the initiative. As they would graduate, others would assume those roles. As a result, an important tradition was already developing.

‘When we showed [Ouchard] something, it was either good or it wasn’t. He rarely explained WHY things should be done in a certain way’ – Gilles Duhaut

The days were divided between high school classes and bow making – usually four hours of each, five days a week. After the school day was done, many bow students would work at makeshift benches they had set up at home. Sometimes the older ones would persuade Ouchard (who had the only key) to let them use the school’s workshop at night. When he would agree, it was often with the caveat not to trust artificial light.

Ouchard loved classical music, as evidenced by his collection of nearly 250 vinyl records. He also enjoyed singing excerpts from his favorite operas and developed close relationships with many string players, including Ruggiero Ricci, his hero. These are among the clues that suggest that Ouchard considered the bow to be not just an elegant and effective tool, but a tool that has a vital musical purpose.

Jean-François Raffin believes that the bows Ouchard made during the years he was teaching in Mirecourt are among his best – more refined than those made for the Vidoudez shop. Perhaps he was finally free to follow his own impulses, but could it also be that this talented group of teenagers was challenging him to bring his A-game?

Pascal Lauxerrois (1959–1994)

Pascal Lauxerrois was related to Jehane Lauxerrois, the daughter of a fine cellist and the mother of Étienne Vatelot, who was Pascal’s uncle. His father, Jean-Paul, was a good archetier and Pascal was therefore steeped in some of the profession’s traditions long before he went to Mirecourt. When he turned 16 he enrolled in the violin making school. A year later he transferred to the bow making school, where Duhaut remembers that ‘Pascal’s progress was so fast that he reached the standard that was expected after two years in only four months. He also understood the characteristics of the wood quicker than the rest of us.’ While some of the students may not have been sure that they wanted to devote their lives to bow making, Lauxerrois knew immediately. He thrived at the school not just because of the challenging interaction with the other students, but because Ouchard proved to be the kind of authority figure who brought out his best. Though things could seem black and white with Ouchard, he was honest and fair. He judged Lauxerrois’s work, nothing more. And despite his unvarnished criticisms, he was caring.

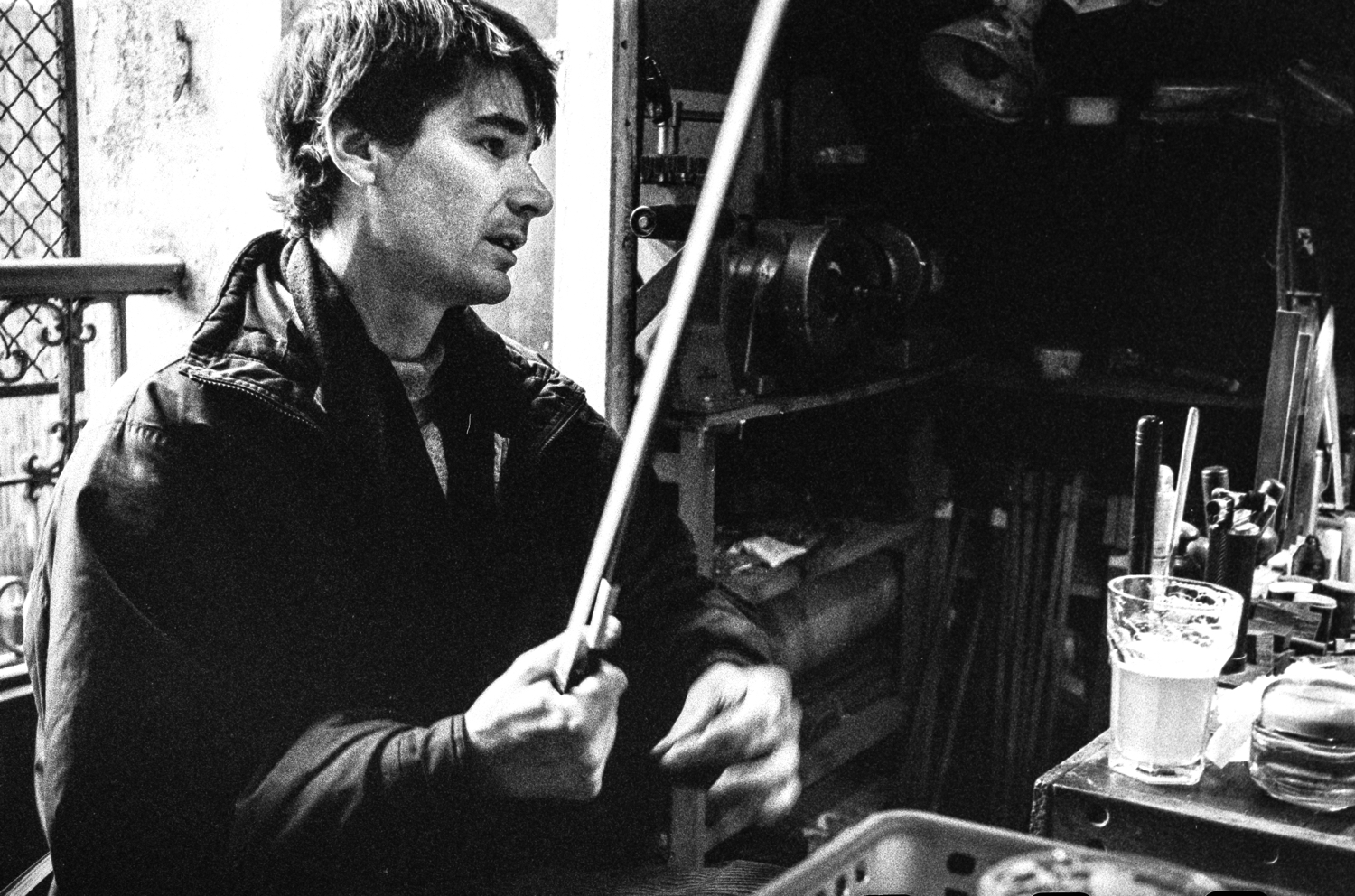

Pascal Lauxerrois in Thomachot’s workshop, Paris

Lauxerrois listened to all kinds of music while he worked and particularly loved Haydn and Bach. He was reserved until he got to know you, say his peers. He was also highly sensitive and exceedingly humble. Duhaut recalls that when someone would seek his opinion, he’d say, ‘You can’t ask me because I don’t know enough.’ But then he would be extremely helpful in a typically modest way. From time to time self-doubt would surface. His wife, Séverine, still remembers his anguish over whether a bow was good enough. When players tried his bows he would leave the room because he feared that their faces, if not their words, would reveal disappointment. It’s easy to see why Grunberger would say that ‘everyone had special feelings for Pascal.’

Though Rolland and Lauxerrois didn’t overlap at Mirecourt, they worked together in the mid-1980s when Lauxerrois would visit Rolland on the island of Bréhat, off the coast of Brittany. Rolland recalls, ‘Pascal had a sharp and quick intelligence along with an incisive sense of humor.’ He was also generous. Charles Espey says, ‘When I first came to Paris and didn’t have a place to stay, Pascal let me stay in his apartment even though he barely knew me then.’

According to Duhaut, ‘Ouchard was always encouraging us to be quick, but without ever sacrificing quality. Pascal worked more quickly than almost everybody, and the quality was always very nice.’ Marc Rosenstiel, a violin maker who shared a shop with Lauxerrois in Grenoble from 1986–89, recalls that he could work virtually non-stop for 24 hours at a time. Once when he was late fulfilling an order for a bow, he worked day and night, finishing it in just two days!

‘I was very sorry to hear of his death! For me it was a disaster because there was nobody else in France who had this passion for expertise’ – Jean-François Raffin

Espey was the first to tell me that Lauxerrois had a special gift for expertise. According to Sylvain Bigot, Lauxerrois was ‘a fabulous expert-to-be’. Bernard Millant himself referred to him in a certificate as ‘mon collègue Pascal Lauxerrois’. Jean-François Raffin recalls that Lauxerrois would frequently visit him for long discussions about bows by the great masters – something that never happened with Ouchard. ‘I was very sorry to hear of his death! For me it was a disaster because there was nobody else in France who had this passion for expertise, like me.’ (This was before he met Bigot and Yannick Le Canu.) Séverine Lauxerrois relates that after working all day at the bench, he could stay up all night studying historic bows. Nehr goes even further: ‘When Pascal would study old bows, he’d look beyond obvious stylistic characteristics and focus on the smallest details. He’d then try to incorporate them in his own bows. Of course we all want to do this. But you can only incorporate what you’re able to see!’

Experts tell me that being a great bow maker is more than what you can do with your hands; it’s also about all the things you’ve learned from countless hours spent studying bows by the great masters. Raffin does not hesitate: ‘For me, Pascal was a great bow maker.’

A viola bow by Pascal Lauxerrois

The viola bow pictured below was made around 1982. In the head and stick we see the influence of Peccatte and Tourte, though the head also reminds Rolland of his own style from their days working together. According to Raffin, the frog is similar to Voirin, as is the camber: ‘It’s very good; not too much by the head.’ With whalebone lapping, the weight is 67 grams.

Pascal Lauxerrois viola bow. The balance point is 19.2 cm and the length of stick 72.8 cm. Photos: courtesy Richard Young

More photosIt is very responsive and athletic, though also dolce when the music requires it. It is quick but never sharp or hard. A fine player can explore a wide range of shadings and articulations with this bow. For instance, one can play spiccato above and below the middle of the bow, in any tempo or dynamic. For a concerto with orchestra, I might choose a bow by Sartory or Vigneron père. But for any of the Beethoven or Bartók string quartets, this Lauxerrois bow inspires as much confidence as a Dominique Peccatte or Kittel.

In part 2, Richard Young explores Ouchard’s teaching methods and the life of Lionel Tasquier.

Richard Young was the violist of the Vermeer Quartet from 1985–2007.

| Selected students of l’Ecole d’Archeterie de Mirecourt |

| 1971–74: Benoît Rolland, Jean-Yves Matter |

| 1972–75: Stéphane Muller, Wilfred Hakoune |

| 1973–76: Gilles Duhaut, Sylvie Masson, Martin Devillers |

| 1974–77: Jean-Pascal Nehr, Christophe Schaeffer, Didier Claudel |

| 1975–78: Pascal Lauxerrois, Jean Grunberger, Stéphane Thomachot |

| 1976–79: Michel Jamonneau, Jacques Poullot |

| 1977–80: Éric Grandchamp, Arnaud Suard, Georges Tepho |

| 1978-1981: Marielle Gobin |

Notes

[1] Loïc & Verena Le Canu, Les Luthiers Français: Les Archetiers Contemporains vol. 4, Le Canu firm, Paris, 1993.